Customer-Centric Focus in the Evolution of Retail Formats: Win by Reducing Friction and Enhancing Customer Experience

January 29, 2021 | By Dinesh Gauri

The “wheel of retailing” describes the journey of retail formats over time. And like the wheels of the bus in the children’s sing-along song, this wheel goes ’round and ’round – although it tends to morph into something new along the way.

So as it rolls back to its natural starting point, it’s worth asking what’s it morphing into next.

New formats in retail typically emerge in the market with low prices, low margins and low reputation. With increases in profits and market share, they roll forward to higher prices, higher margins and higher reputation. Eventually, newer forms of the outlet disrupt the market by entering the environment with low prices, low margins and low reputation, and the circle is complete.

This cycle has driven most of the significant changes in retailing formats.

About 200 years ago, for instance, retailers usually were small general stores owned by a single family. Customers would ask a clerk to bring out merchandise, and then they often haggled over the price.

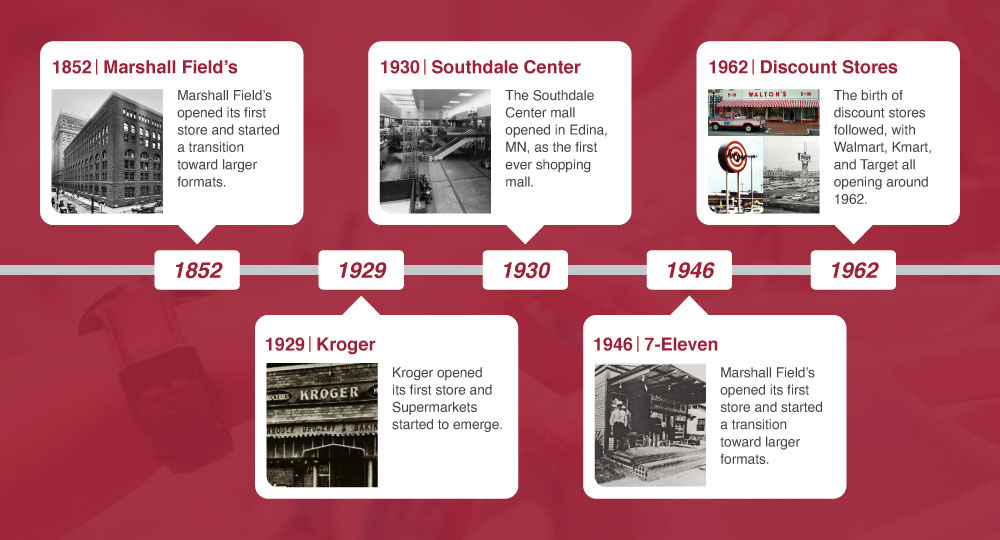

In 1852, Marshall Field’s opened its first store and started a transition toward larger formats. Urban department stores, in particular, offered a much larger assortment of products under one roof and at fixed prices.

Supermarkets emerged in the early 20th century, with Kroger opening in 1929, and the proliferation of retail formats gathered pace shortly thereafter. The first mall opened the next year, allowing shoppers to access a variety of stores under one roof. 7-Eleven opened its first convenience store in 1946 and started a trend by providing extended hours of operation (from 7 a.m. to 11 p.m.). The birth of discount stores followed, with Walmart, Kmart and Target all opening around 1962.

Non-store shopping options also rolled along. Customers once ordered by mail from catalogs, then (by phone) from ads on radio and later television, then from websites, and then from Amazon and eBay.

Today the market has moved to integrated channels that once again are marked by low prices, low margins and, in some cases, low reputation. But the wheel of retailing continues to rotate, faster for some than for others.

At the Retailing Thought Leadership Conference organized by the Sam M. Walton College of Business in October 2019, I was part of a group tasked with discussing the evolution of formats in the dynamic and ever-changing world of retailing. Leading academics from the University of Washington, the University of Texas, the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Southern Methodist University and the University of Arkansas worked with practitioners from Walmart, J.M. Smucker Company and Whytespyder.

During the event and in the months following it, we studied the research done in this field and came up with a framework that illustrates the two main paths for retailers that want to stay out front in the race toward increases in profits and market share.

With multiple formats competing for customers, we realized that quality and price considerations no longer are the lone drivers of buying decisions. To succeed in the next stage of retailing, stores also will need to reduce the friction in the customer journey, enhance the customer experience, or both.

Path 1: Reducing Friction for Customers

The first path takes away obstacles and impediments by shortening wait times, reducing inconveniences and eliminating unnecessary steps in a customer’s journey.

Amazon is the classic example of a retailer using technology to remove obstacles and impediments. It reduced the effort and complexity of online shopping, as well as the time buyers had to wait before receiving merchandise with innovations such as “one-click” ordering, a sophisticated product recommendation algorithm and a supply chain capable of providing free second-day shipping (now even reduced to one day or less in certain areas).

Most retailers today are working to reduce friction by coming up with advancements that make it easier to order or return products and that increase the speed of delivery. Robots, drones, autonomous vehicles and other technologies are increasing retailers’ efficiencies online, in stores and throughout the supply chain.

In 2019, for instance, almost 30 million consumers used a voice assistant such as Amazon Echo or Google Home to help in them shop for and/or buy products online. Apps have made it easier to shop and buy from a phone or tablet. And while Amazon started the “speed wars” in delivery, other retailers have followed suit, including smaller merchants that are using ecommerce fulfillment companies like Deliverr to help them compete.

Because buyers typically can’t touch, try on, smell or examine products online the way they can in person, returns have become a cost of doing ecommerce business. Making those returns easier is an important way online formats are looking to reduce friction, which makes reverse logistics an important factor. Amazon now accepts returns at Kohl’s stores, for instance, and online clothier Rent the Runway allows returns at Nordstrom locations. Walmart, meanwhile, announced a partnership with FedEx in December 2020 that allows customers to start returns online or in the Walmart app and have the items picked up from their homes at scheduled times.

Retailers also are reducing friction at physical stores in several innovative ways, including with touchless transactions and in-store or curbside pickup options of items purchased online. These concepts are typically integrated into existing stores, but they also are leading to new formats. Target, for instance, has opened smaller stores with limited assortments but that also provide convenient locations for customers to pick up online purchases.

Many of these advancements, of course, were shot into hyperdrive with the pandemic, which also led to other friction-reducing innovations. Grit Grocery in Houston, for instance, borrowed from a popular format in South Asia and introduced a “store on wheels” concept that brings locally sourced produce, meats and other products into neighborhoods.

All these format innovations have at least one thing in common: They seek to reduce the friction in the customer’s journey.

Path 2: Enhancing Customer Shopping Experience

The second path creates pleasurable experiences based on customers’ preferences and behaviors.

For example, Lululemon, the apparel retailer that caters to “yoga, running, training and most other sweaty pursuits,” enhances its customer experience by building a community around engagement in a healthy lifestyle. It has built yoga- and fitness-centric communities by engaging local yoga and fitness instructors and sponsoring events at stores. Its in-store models include a “sweat studio” for trying out merchandise and a “fuel bar” for healthy refreshments.

Physical stores are playing a key role in enhancing the experience of the customer’s journey. Regardless of whether the retailer is best known for ecommerce or for its physical locations, zero-inventory stores, as they are known, have become an option for building brand awareness and customer engagement. The Journey, a zero-inventory concept in Toronto by Canada Goose, allows shoppers to traverse an icy rock face and try on the brand’s parkas in a snow-filled room.

Other retailers are using in-store experiences and special “retailtainment” events to draw in customers or offering new options like creating areas in their stores that focus on resale products.

Technology, of course, plays a big role in enhancing experiences. The idea of immersive retail, for instance, involves using mixed reality apps to conduct virtual tours so customers can see how a product looks and is used in a simulated real-life environment. Nike, for instance, uses an augmented reality app that allows shoppers to try on shoes virtually.

Online retailers also use technology to provide shoppers with personalized information like style guides, design options and product reviews. Stitch Fix, for instance, bills itself as a personal style service and uses algorithms and data science to personalize clothing items based on size, budget and style.

Another way some retailers are enhancing experiences (as well as reducing friction) is with cashless stores like Amazon Go convenience stores. These stores use technology to allow shoppers to pick up items and walk out without going through a checkout process.

An increasing comfort level with online shopping has led many manufacturers to sell directly to customers rather than sticking strictly to their traditional business-to-business models. PepsiCo, for example, launched two websites – PantryShop.com and Snacks.com – so customers can order online and have their favorite brands delivered within two business days. Manufacturers not only are creating online stores, but in some cases are opening zero-inventory, flagship or outlet stores.

Technology also can affect experiences in a store because automated process and robots often improve efficiencies around things like cleaning, delivery and inventory management, all of which can make a shopping trip more enjoyable.

A human touch, however, is still relevant, and personalized shopping is another trend that enhances experiences. Research continues to show that a knowledgeable sales associate can be the face of the retailer and a differentiator in purchasing decisions. Equipping and training associates to use technology that helps with things like making recommendations adds value to the experience.

Traditional online-only merchants have recognized the need to offer sensory information to shoppers, and some are expanding to more of an omni-channel approach. Large and small online retailers have begun using “pop-up stores” to meet this need. These stores open for a defined period, from a few days to a few months, with the objective of offering customers a tangible experience they can’t find online. They also allow brands to experiment with new concepts and build closer connections through personalized service.

Avoiding Flat Tires

The wheel of retailing doesn’t always roll easily down smooth roads. There are plenty of obstacles, not to mention blind curves, and academics and practitioners alike have plenty to consider and research.

Retailers testing zero-inventory and pop-up store concepts are still learning how far customers are willing to travel to those stores and whether the costs associated with opening and running them are worth the returns. And the jury also remains out on the effectiveness of ideas like using virtual reality technologies or partnering with other retailers. And then there are the questions about how trends that began because of the pandemic will affect customers’ expectations and shopping patterns in the future.

Regardless, newer digital-first and physical-first players will continue to develop innovative customer-centric formats, which eventually will morph into integrated retailers, thus leaving space for more new players to enter the market. And, hence, the wheel of retailing will keep spinning.

As always, customers will be the focus of these experiments and ultimately will benefit from the best of the new concepts in retail formats. Some retailers, like a jalopy abandoned on the side of the road with four flat tires, won’t adapt to the changes and will go nowhere other than the junkyard. But the companies that successfully reduce fiction for customers and enhance their shopping experience will roll forward into the future.