Inflation is raising the price of food (and nearly everything else).

Recent supply chain disruptions make it tempting to explain that inflation by scapegoating high transportation costs. But the data does not support that argument. Though freight rates have risen sharply during the pandemic, they account for a very small portion of the inflation we are experiencing in many products.

To better understand the forces at play, we examine the cost of a heavily imported staple of many holiday dinners: seafood. Seafood is a small part of the average American household’s spending—accounting for 0.278% of the weight for the entire Consumer Price Index (CPI) and accounting for 3.6% of the weight for the CPI subindex Food at Home—but offers useful insight into broader inflationary trends.

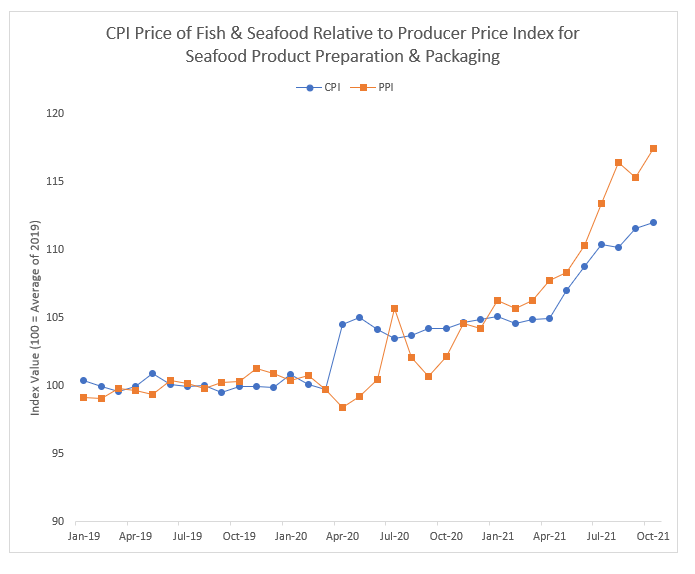

Retail and Production Prices Rose Well Before Import Prices

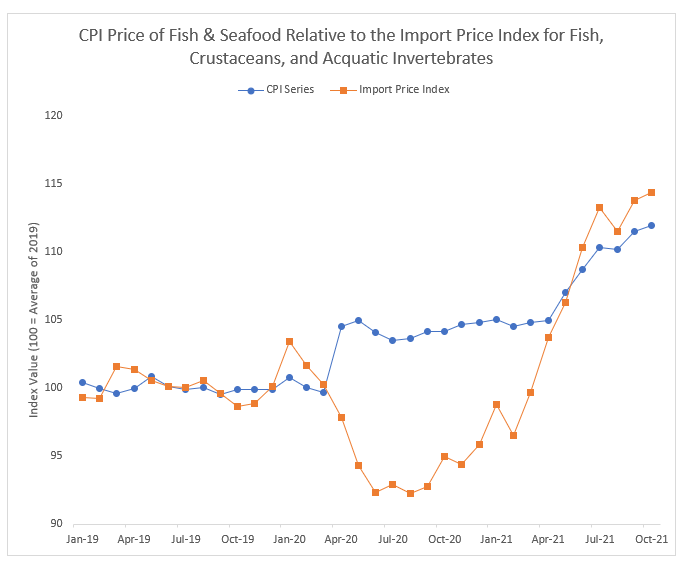

Lockdown orders, restaurant closures, and uncertainty caused Americans to stock up on groceries during the pandemic’s early weeks. That demand spike — coupled with a rise in production prices — fueled a ~5% uptick in the retail price of seafood in spring 2020. Retail prices, as measured by the fish and seafood CPI and producer prices received by seafood product preparation and packaging producer price index, have risen in near lockstep ever since, as shown in the first figure.

Conversely, just as retail and production prices began their precipitous climb, seafood import prices fell below 2019 levels in 2020. They remained there for the next year. This is shown in the second figure, which plots the fish and seafood CPI relative to the import price index for fish, crustaceans, and aquatic invertebrates.

High Freight Rates Only Tell Part of the Story

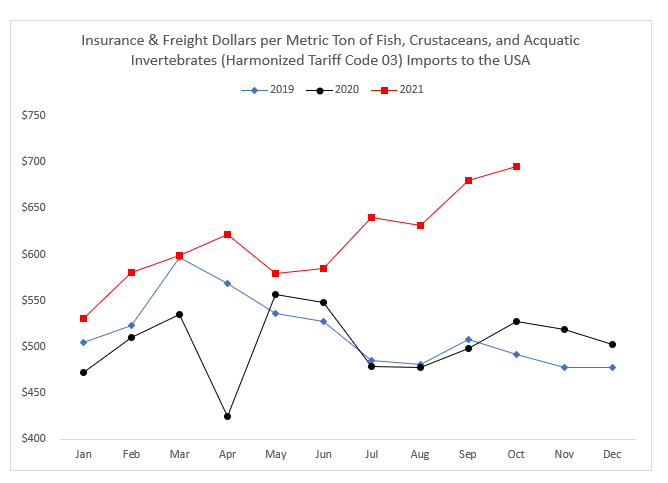

Record demand and historic uncertainty have strained transportation systems throughout the pandemic. Those systems have responded by moving unprecedented amounts of freight, but tight capacity has left shippers little choice but to pay rates that would have been unthinkable in 2019.

Seafood is typically transported in refrigerated containers on ships, so its freight rates reflect recent capacity issues and port congestion. As shown in the third figure, insurance and freight costs were ~31% higher in October 2021 than in October 2020, which was calculated by merging data sources from the Census Bureau’s USA Trade Online database for fish, crustaceans, and aquatic invertebrates.

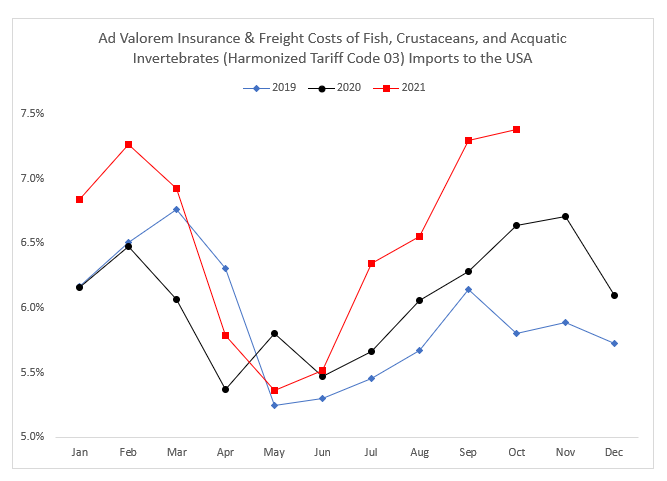

However, that staggering shift does little to explain the inflation we are experiencing. The reason for this is that insurance and freight costs are small relative to the customs import value of fish, crustaceans, and aquatic invertebrates. This can be seen in the fourth figure where we calculate what economists call ad valorem insurance and freight costs — the ratio of insurance and freight costs divided by the customs import value of the products.

Insurance and freight costs were roughly 6% of customs import value in 2019 and have increased to only 7.5% today. Stated another way, in 2019, insurance and freight prices were $0.51 per kilogram of imports, whereas the customs import value was $6.89 per kilogram of imports. In October 2021, insurance and freight prices were $.70 per kilogram of imports, whereas the customs import value was $8.03 per kilogram of imports. As such, while insurance and freight costs per kilogram have risen $0.19, the commodity price of imported fish, crustaceans, and aquatic invertebrates has risen by $1.14. So, the commodity price increase far outweighs the increase in insurance and freight costs on a per kilogram basis.

If Shipping Prices Are Not to Blame for Inflation, Then What Is?

High shipping costs only a minority of the recent uptick in seafood prices. So, how do we explain the rest? Labor issues bear some of the blame, but the primary reason is rising commodity costs.

Commodity costs are driving up the price of nearly everything. While some, including Orlando seafood restaurateur Brennan Heretick, initially tried to eat the rising costs of seafood and products ranging from cleaning supplies to take-out boxes, they had little choice but to pass the costs along to their customers eventually. In July, Heretick reported that his restaurant recently had a month of record-breaking revenues — but still lost $14,000. “We hope that…everybody’s understanding that we did everything we could.”