State Highway 9 in Colorado weaves its way through the Rocky Mountains, crossing the Continental Divide at Hoosier Pass and giving motorists access to 139 miles of breathtaking natural scenery – views of rivers, forests, meadows, reservoirs, and wildlife. But watch out for the critters, especially the big ones – mule deer, elk, and bear, for instance.

Around 3,300 collisions between wildlife and vehicles are reported each year in Colorado, killing many of the animals and causing an average of about $3,100 per incident in property damage and $66.3 million in annual medical expenses.

A nine-mile stretch on the northern most section of Highway 9, however, includes a series of five wildlife crossing structures – two overpasses and five underpasses – as well as wildlife escape ramps and wildlife guards (eight-foot-tall fences) that are all designed to help animals and motorists traverse the highway more safely.

While some research indicates such structures are effective, Tandem Young noticed a peculiar trend when he mined the data for a capstone project in his advanced economic analytics class.

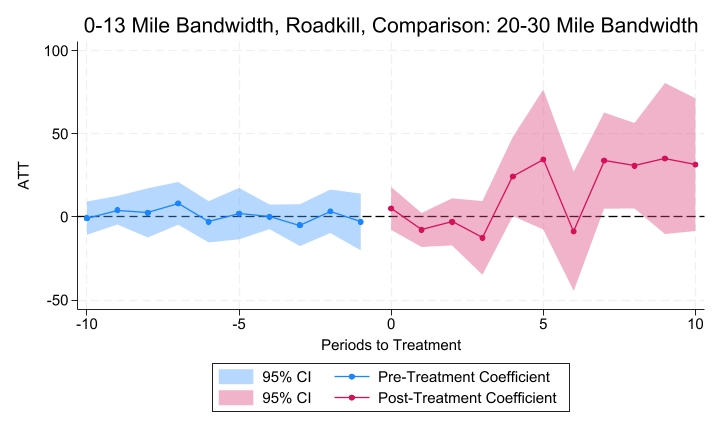

As expected, he found that the number and severity of car crashes involving animals across Colorado decreased after crossing structures were put in place and that roadkill instances near the structures declined – at least initially. The surprise was that after three years the roadkill instances went up to levels above what was the norm before the crossing structures were built.

Young, who earned undergraduate degrees in finance and digital marketing from Arkansas Tech, is completing a degree in the 10-month Master of Science in Economic Analytics program at the Sam M. Walton College of Business. After learning about analytics tools and techniques in the fall of 2023, he and his classmates spent the spring semester applying what they learned on capstone projects for their Economic Analytics II class.

One of his professors, Doyoung Park, earned his Ph.D. from the University of Colorado and was familiar with research on roadkill incidents. Park and Hyunseok Jung, another economics professor, shared a study on roadkill incidents in Washington and encouraged Young to find and analyze more data. As a native of Dover, Arkansas, and a frequent visitor to Colorado, Young’s love for the outdoors immediately drew him to the assignment.

Colorado has been building wildlife crossing structures since 1953, including those along Highway 9, so Young used data from the state’s Department of Transportation to examine 28 structures that opened between 2007 and 2021. He also pulled a comprehensive dataset of roadkill events from 2007 through 2022. Both datasets were geocoded, giving him latitude and longitude points.

“So using Python, an open-source programming language, I was able to write an algorithm that would find the minimum distance to a crossing structure for each roadkill point and assign it to that structure for every year that the structures existed from 2007 to 2022,” Young said.

Young’s analysis focused on a 13-mile radius of the structures, with larger “rings” used for control regions. Since the structures weren’t all built at the same time, he used an advanced econometric technique known as “staggered difference in differences” to analyze the data. He also added other control factors like county population statistics and temperatures that provide clues about vehicle traffic counts and animal migration patterns.

The most surprising result of the data, he said, was the increase in roadkill events beginning three years after the crossing structures were built. In fact, with the exception of one year, the annual roadkill instances after the third year were all higher than before the crossing structures were built. For instance, five years after a structure was built, the 0-13-mile radius saw up to 75 more roadkill events annually compared to the 20-30-mile control region.

“What we’re thinking is that the structures are giving the animals the ability to go to places they typically wouldn’t have the option to go,” Young said. “So it’s almost encouraging them to be near the road and increasing the roadkill outcomes.”

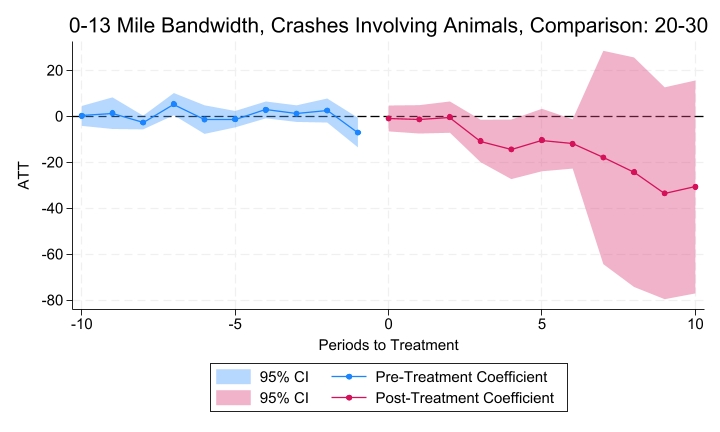

Vehicle accidents involving animals showed no change for the first three years, which Young said might indicate a hesitancy by animals to use the structures or a migration effect of the animals that could be offsetting the initial expected outcomes. After three years, however, accidents involving animals decreased significantly.

Accidents not involving animals, meanwhile, decreased significantly in the first three years after a structure was built, then returned to levels slightly below the norm prior to having the structures. This suggests that motorists are more cautious in general after the introduction of a structure, Young said, but revert to their old ways of driving once the structure becomes familiar.

This type of economic research, Young said, should be of interest to taxpayers, municipal governments, and insurance companies, as well as the agencies building the structures like the Colorado Department of Transportation and Colorado Parks and Wildlife.

But Young believes there is far more that they can learn from the data by adding in more control factors and digging deeper into patterns.

“We’re definitely going to continue with this research,” he said. “Doctors Park and Jung and I plan on conducting more analysis and trying to get more granular by using some other techniques to see if we can get something a little bit more descriptive. Right now, it seems to be functioning in a weird inverse. But we feel like we could get to the bottom line where it’s not quite so noisy and get a definite answer as to how this works.”

He said they also want to apply more cost-benefit analysis to see the monetary advantages or disadvantages of the crossing structures for individuals in Colorado. At that point, they hope to publish their results.

Understanding how to do this level of economic analysis so quickly is something Young said he never envisioned for himself when he entered the program.

“I definitely understand why I’m doing what I’m doing and how it works so much more, because I have to present on it and know it forwards and backwards,” he said of the capstone project. “Coming from my undergraduate degree in finance and then going into this program, I never would have seen myself here in a year’s time. So I feel like I’ve learned so much.”

The master’s program, in fact, has inspired Young to pursue a doctorate degree in economics and perhaps a career in teaching.

“I’ve definitely enjoyed more of the applied research side of things,” he said. “I think that interests me more than theoretical. But I could see myself doing academia. I think teaching would be very fulfilling, just seeing the progress of students over time and making an impact in people's lives. And to do that while also conduct research in the academic field, I think be very appealing.”