EPIC Spotlight: Doyle Z. Williams

February 11, 2021 | By Sandra Birchfield

A video prepared for Dean Williams' retirement in 2006.

The gathering was like a Who’s Who of Arkansas.

Gov. Mike Huckabee and Helen Walton were there. So were the media, state and local government leaders, University of Arkansas administrators, faculty, staff, alumni, supporters and the Board of Trustees. College students were transported from campus to the downtown Hilton Hotel so they could attend.

As people milled about, most were not sure why the event was called. Doyle Z. Williams, the business college’s dean, and University of Arkansas Chancellor John White knew: The Walton Family Charitable Support Foundation had pledged $50 million cash upon the announcement of the gift to the University of Arkansas College of Business Administration.

The audience gasped.

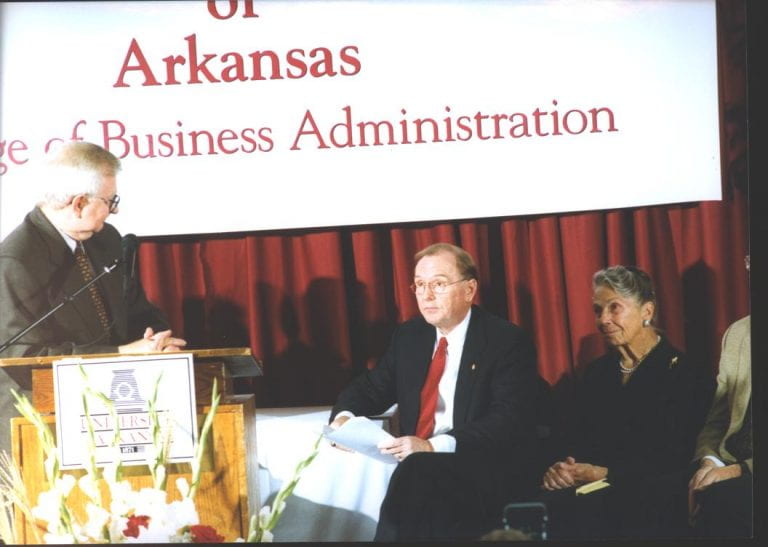

Pictured above: Dean Williams, Chancellor White and Helen Walton

The donation, which was announced Oct. 6, 1998, was the largest in the school’s history and the largest single cash donation ever given to a public American business school at the time. The news, so big, even made The New York Times. Williams had worked diligently with his associate and assistant deans, department chairs and White to assess the college’s needs and goals. The amount of money needed to fulfill those dreams seemed almost unthinkable.

“We made a long list of projects we wanted to undertake, things like scholarships, endowed chairs for faculty, establishing several research centers, curriculum development and so on,” says Karen Pincus, an accounting professor during Williams’ tenure who was on the planning team. “Imagine our shock when the foundation said they would fund the entire list!”

The college was given a new name: The Sam M. Walton College of Business. “This is noteworthy because Sam Walton was arguably the most successful entrepreneur in the history of the United States,” Walton College Dean Matt Waller says of Walmart’s founder.

The announcement was only one of several accomplishments during Williams’ tenure as Walton dean from 1993 to 2005. The Walton College also received its first ranking as a Top 25 public business college by U.S. News and World Report, and Williams was behind the founding of the Arkansas Business Hall of Fame. From there, his accomplishments continued, including founding the college’s Dean’s Executive Advisory Board, the annual Business Forecast Luncheon and the college’s Alumni Awards. Under his leadership, Walton’s diversity office became not only the first at Walton but at any Southeastern Conference business school. Williams helped drive the expansion of Walton College’s campus, which, early in his deanship, consisted of only the Business Building on McIlroy Avenue and grew to include the Donald W. Reynolds Center for Enterprise Development and Willard J. Walker Hall.

Williams was recently named to the National Accounting Hall of Fame, which honors accountants who have made, or are making, significant contributions to the advancement of accounting. Since its inception in 1950, the America Accounting Association has inducted 106 members.

When Williams arrived at the University of Arkansas, he already had a strong résumé as the founding dean of the School of Accounting at the University of Southern California.

“He knew what it took for a business school to be nationally competitive,” White says. “I did not have to paint a picture for him because he had already visualized what he wanted for the UA business school.”

After Williams arrived, he and then-Associate Dean Bill Curington invited students to monthly breakfasts to exchange information, ideas and concerns. When students shared that they wanted smoke-free buildings on campus, Walton became one of the first to make that move, Pincus says.

“Doyle was a great listener,” says Matt Waller, Walton College dean. “If you brought a problem or opportunity to him, he would ask lots of questions and then listen carefully to your answers and then ask follow-up questions. It would turn into an engaging and enjoyable conversation. On big decisions, he would get input from many different people, but finally he would make a decision, even if it were not popular.”

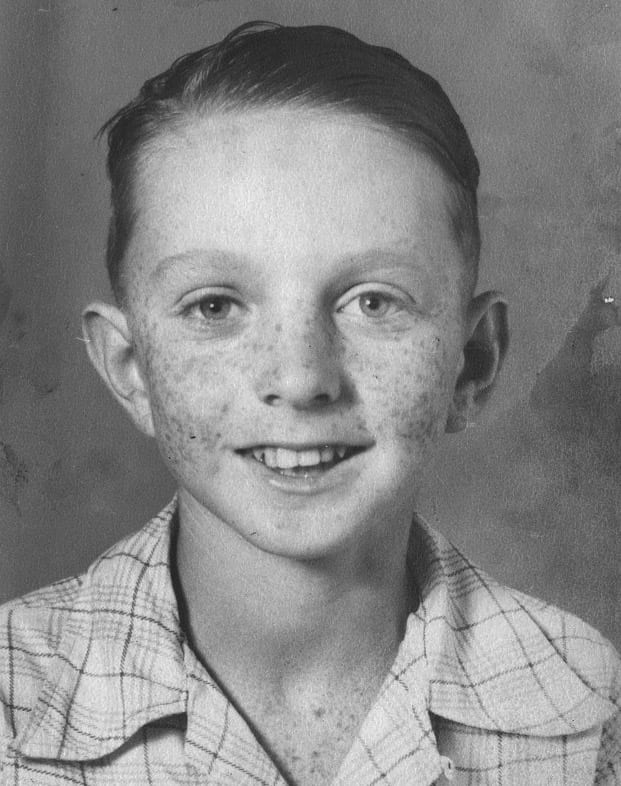

Rural Roots

Hard work and obstacles were no stranger to Williams, whose middle name, Zane, came from Zane Grey, a best-selling Western novelist from the early 20th century. Williams grew up on a cotton and hay farm in the community of Ajax, Louisiana, about 60 miles southeast of Shreveport. Before he reached the age of 10, his family’s shotgun house burned down. They relocated to an abandoned sharecropper’s shack and cooked from donated pots and pans to help re-establish themselves. Not long afterward, a flood forced them out of their home and into a Red Cross tent camp.

“In the summer, we moved back in,” Williams told the Northwest Arkansas Business Journal in 2002. “The government, to help with mosquito control, came by and sprayed all our houses with DDT.”

And then Williams lost a younger brother, who fell into the fireplace and died in his mother’s arms en route to the nearest doctor.

But survive, the family did. Williams’ father borrowed money to put toward 57 acres of timberland and paid it back in 10 years. They lived in another abandoned house while his father built them a new, permanent one – without plumbing, a telephone and other creature comforts that were common in many households. But it was home.

Williams spent much of his adolescence picking cotton on the family farm without the aid of any mechanical equipment. One year, the family, including his two brothers, sold pecans from their trees and earned enough money to buy a pickup truck.

The family got by in the small community where Williams was one of seven students in his high school graduating class. His father was a high school graduate while his mother dropped out in the 10th grade to help take care of her seven younger siblings. The couple wanted Williams to go to college. With $20 and their blessing, Williams was off to Northwestern State University of Louisiana in Natchitoches. Though only 25 miles from Ajax, Williams lived on campus.

“I thought I had died and gone to heaven,” Doyle Williams said in 2002. “I had never had a shower in my life. We had baths in washtubs. I had never had a bath in warm water. … I thought, ‘I’m not going to do anything to give this up.’”

To pay for his education, Williams worked early morning hours at the campus dining hall and, during the summers, he worked long days under the blistering sun in the family’s hay fields, which served as an incentive to stay in school.

Williams majored in science, but chemistry was a stumbling block. Through college advising and an opportunity to work in the accounting office of a farming supply distributor, Williams shifted his focus to accounting, earning his degree in only three years at the age of 20 to cut expenses. He worked for a New Orleans accounting firm for a year before realizing teaching was his calling. Williams was accepted to Louisiana State University, and he plowed his way through, earning a doctorate at the age of 25.

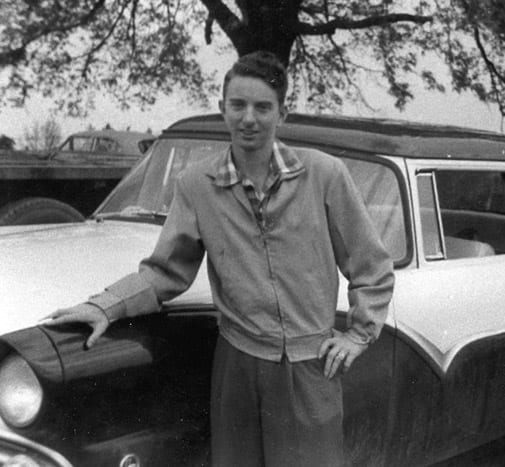

A Career and a Wife

His first professorship was at Texas Tech University in Lubbock. While living there, Williams attended a young professionals’ group at his church where he met his future wife, Maynette Derr, who would become a home economics professor at Texas Tech shortly thereafter. The couple married in August 1967 and are the parents of two children, son Zane and daughter Elizabeth.

Shortly after the couple wed, they moved to New York City so that Williams could work with the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants. They then moved again so that Williams could assume a visiting professorship at the University of Hawaii before returning to Texas Tech, where he became department chair.

William Holder, dean of Leventhal School of Accounting at the University of Southern California, began his professorship at Texas Tech while Williams was there.

“It didn’t take me long to figure out that he was the catalyst and glue that held everything together there,” Holder says. “He was the individual who attracted all of those people that then attracted me to join them.”

Holder says the few years he spent at Texas Tech were some of the most formative in his professional life, much of it due to Williams’ guidance and leadership.

Administrators with the University of Southern California hired Williams in 1978 to help start its school of accounting. A year later, Holder joined the faculty as well. He says Williams had ways to get people to listen, understand and appreciate what needed to be accomplished.

“He was very quiet and understated,” Holder says. “He was always calm and thoughtful.”

Under Williams’ leadership, an accounting school was created and, to this day, the University of Southern California attributes that success to Williams. Business colleges across the nation were watching, but it was the University of Arkansas that made him an offer he couldn’t refuse: to become dean of its business college and build its program. Williams’ departure worried Holder, though he recognized Williams was following his dream. “I was very concerned about whether I could continue to succeed in the absence of his leadership,” Holder recalls.

But through his sadness, he knew that the University of Arkansas was gaining a great leader.

“You could see what was going to come to pass before it did, and you knew it was probably a matter of time before somebody had the good sense to recognize his genius and make him an offer that would pull him away from USC,” Holder says.

Business College Grows

After Williams arrived at the University of Arkansas, he met with faculty and drove around the state to speak to employers and alumni as he gathered information on what people wanted to see from its business program.

“I worked a lot of long hours, often six to seven days a week, during his early years at Walton – and that was okay – because I knew he was working as much and appreciated and respected what I brought to the table,” says Nancy Hart, Walton’s Office of External Relations’ director of constituent relations.

In June 1997, a month before White was appointed chancellor, Williams invited him along with the university’s deans and vice chancellors to a weekly Saturday morning meeting at Walmart’s home office in Bentonville.

“This gave me an opportunity to meet many UA administrators and Walmart executives and observe Doyle’s networking skills,” White says.

Pictured above:(Front row) Gov. Mike Huckabee, Helen Walton, Rob Walton, John A. White; (back row) Frank Oldham Jr., B. Alan Sugg, Curtis Shipley, Doyle Williams

When Williams approached White about his plan to ask the Walton Family Charitable Support Foundation for an endowment, White encouraged him to think beyond his initial goal. Williams did, and the goal was met. Hart and her team meticulously, and surreptitiously, planned for the announcement in a series of events: a press conference, reception, VIP luncheon, transportation and even live music. Security detail was needed for Gov. Mike Huckabee, university dignitaries as well as Sam Walton’s widow, Helen Walton, and her son, Rob Walton, who was chairman of Walmart at the time.

“Some were guessing that it would be a gift announcement, but no one anticipated the size of the gift,” recalls Hart. “It was a surprise to almost everyone present.”

More than 20 years later, the gift is still felt today.

“The $50 million endowment from the Walton Family Charitable Support Foundation was a stamp of approval that was noticed in business schools around the world,” Waller says.

It raised the stature of the University of Arkansas.

“The event with Mrs. Helen Walton, Gov. Mike Huckabee, Doyle and myself continues to stand out in my mind as a milestone during my chancellorship,” White says.

The Walton College quickly gained national recognition, and in 2006, U.S. News and World Report ranked it 24th in the nation among undergraduate public business schools. More recently, the college’s undergraduate supply chain program was ranked No. 1 in North America by the leading global research firm Gartner.

Williams also helped create the Arkansas Business Hall of Fame. Each year, the Hall of Fame inducts four business leaders of integrity in Arkansas that culminates with a ceremony and celebration at the Statehouse Convention Center in Little Rock.

“The Arkansas Business Hall of Fame was Doyle’s idea,” White says. “It proved to be a winner for the college, the university and the state.”

The annual Business Forecast Luncheon, which attracts more than 1,000 attendees annually, was also Williams’ idea, says Waller. Held by the university’s Center for Business and Economic Research, the event attracts world-renowned economists and business leaders, who share their insights from a global, national and local perspective. “If you ever come to an event, you can feel the energy in the meeting,” Waller says.

Williams also helped establish the Walton College’s Office of Diversity and Inclusion.

“We were one of the first few colleges of business in the United States to have such an office,” Waller says. “Doyle was clearly very forward thinking.”

Through the Walton Family Charitable Support Foundation, the university established the Doyle Z. and Maynette Derr Williams Chair in Professional Accounting in 2005. Karen Pincus became the first chair holder.

“People loved and respected him – both professionally and personally,” Hart says. “He was successful because he truly had a ‘servant’ attitude. He was willing to serve whenever or wherever. It didn’t matter whether it was a prominent position or not.”

Williams retired from the University of Arkansas with emeritus status in 2006, a year after leaving his post as dean. He and Maynette now live in Silver Spring, Maryland.

Leader in Accounting

In addition to his stints at Arkansas, Texas Tech and the University of Southern California, Williams accomplishments are plentiful and include serving as president of the American Accounting Association from 1984-1985 and chair of the Board of Directors of the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB), an international accrediting body for business schools, from 2004-2005. He also served as executive director of the Accounting Doctoral Scholars Program, administered by the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants, from 2008-2012.

He was twice awarded the Federation of Schools of Accountancy (FSA)/Joseph A. Silvoso Faculty Merit Award for distinguished contributions to the federation, to the profession of accounting and to accounting education. He received the American Accounting Association’s Outstanding Accounting Educator Award in 1996 and was the fifth educator to receive the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants’ Gold Medal for Distinguished Service in 2002.

“His philosophy was: ‘The keys to success are simple – have sound moral values, seek to make a difference, seek to work harder than anyone else in the organization, value the advice of others and bury your ego,’” Pincus says. “He lived that philosophy.”

But his accomplishments could not have been fulfilled without the teamwork afforded both the Walton College and university, his wife says.

And one other person.

“Doyle was most fortunate to have Maynette by his side,” White says. “She invested herself in the college and university. They were an awesome team.”