Working Paper | Reducing the Cost of Last Mile Delivery: A Channel Shifting Behavioral Approach

By Rodney Thomas and Travis Tokar

Abstract

The increasing prevalence of ecommerce has presented an abundance of challenges for retailers. Among the most prominent of these is the high cost and operational complexity of home delivery for online purchases. While alternate delivery channels, such as buy online pickup in store, have recently been developed, shoppers still typically prefer the convenience of delivery – particularly when retailers offer it at the low cost and high speed of today’s competitive environment. In this paper we test the efficacy of two potential methods of shifting consumers’ delivery selection away from costly delivery and toward the much more favorable pickup option – namely sustainability-oriented information labels and monetary discounts. Our results show that information labels are indeed effective at shaping behavior and are far more impactful than the modest discount retailers tend to offer. Further, we find no evidence of negative second-order effects related to the messages. Thus our work presents retailers with a possible win-win tactic for easing the cost and challenge of ecommerce without losing the patronage of customers.

INTRODUCTION

Last mile delivery is a complex and expensive challenge for retailers (Praet et al 2020). As the highest cost-to-serve channel in retailing, last mile delivery compresses margins (Lee and Whang 2001). Home deliveries also cannibalize higher margin sales in other channels thereby creating an adverse margin mix. Ecommerce sales growth exacerbates the problem because increasing last mile delivery volume strains retail supply chains and drives down efficiencies (Lu et al. 2022). At the same time, customer expectations for fast and free last mile delivery continue to intensify, thus reducing the viability of premium pricing offsets (Reed et al. 2022). Time sensitive customers appreciate the convenience of home delivery - especially when it is free of charge. The confluence of these customer trends and operational realities has created a perfect storm that jeopardizes retail profitability. Clearly, last mile delivery is an important issue worthy of in-depth scientific inquiry (Ha et al. 2020).

Existing research into last mile delivery has focused on operationally driving down costs. Route optimization is a common approach that reduces travel mileage and corresponding fuel consumption (Wang et al. 2020). Consolidation of multiple orders via batching or grouping techniques creates delivery density efficiencies (Castillo et al. 2018). Networks have evolved to include micro-fulfillment centers or ship-from-store fulfillment to minimize last mile delivery times and distances (Robinson et al. 2023). Crowd sourcing, centralized order lockers, and peer-to-peer delivery models have emerged as non-traditional attempts to facilitate productivity (Qi et al. 2018, He et al. 2023). All of these approaches have made significant contributions to retail supply chains and removed costs from ecommerce shipments. However, even with these gains, last mile delivery still remains the highest cost channel in retailing, and volumes continue to grow (Fatehi et al. 2023). Another solution to this problem is needed.

Although customers increasingly crave free expedited home deliveries, many are also becoming more conscious of environmental and social sustainability issues (Duan et al. 2021). These customer segments prefer sustainable supply chain operations and want products that do not adversely affect society. In some ways, last mile delivery may conflict with customer sustainability preferences because this channel produces additional cardboard and packaging wastes (Yang et al. 2023). Likewise, home deliveries can also contribute to neighborhood traffic congestion, road safety issues, and incremental noise pollution (Cardenas et al. 2017, Deng et al. 2021). Insights from Social Exchange Theory (Thibaut and Kelley 1959) suggest that last mile sustainability externalities may fundamentally alter channel decisions and exchange relationship dynamics. In particular, customers may be less likely to select last mile delivery of their purchases when they are aware of sustainability consequences associated with channel options.

This research seeks to determine the conditions that enable retailers to shift last mile customer demand to lower cost channels by increasing awareness of sustainability consequences. To learn more about this phenomenon, a series of vignette based experiments were conducted with experienced omni-channel customers. Participants were asked to select between last mile delivery and store pickup channels. This channel selection decision was conducted in the presence or absence of explicit sustainability consequences and financial incentives. Results of the experiments show that retailers can move customer demand to a less expensive channel by highlighting the environmental and social sustainability implications of last mile delivery. Of particular note, this cost saving shift from last mile delivery to store pickup did not adversely affect customer satisfaction or re-purchase intentions.

Results of these studies have meaningful implications for research, practice, and policy in retail supply chains. They make a unique contribution to the last mile delivery literature by identifying a new approach to reducing adverse profit effects in the highest cost-to-serve channel. They also contribute to Social Exchange Theory by demonstrating that basic exchanges are more nuanced than previously conceptualized with product delivery mechanisms taking a more prominent role within relationships. From a managerial perspective, our research shows a novel channel shifting approach can dramatically reduce supply chain costs without large investments, significant process changes, or reduced customer satisfaction. In terms of public policy, our findings suggest that many customers will make greener or socially conscious decisions when they are aware of sustainability consequences. Free market mechanisms may be a viable alternative to legislative mandates when sustainability information is widely available. As these examples show, this research has positive effects on multiple stakeholders.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

Last Mile

The “last mile” in retailing refers to delivering a package to a final customer (Praet and Martens 2020). It completes the transfer of products from a retail facility to a residential location and concludes traditional supply chain activities that provide utility to customers (Lu et al. 2022, Deng et al. 2021). Volumes in this delivery channel have dramatically increased over the past decade due to significant e-commerce growth (Masorgo et al. 2023). Global online retail sales now exceed $4 trillion with annual growth rate projections around 20% (Liu et al. 2023, Lyu and Teo 2023). In the United States alone, online retail sales translate to over 24 billion parcel deliveries each year (Lim et al. 2022). Due to the large scale of these operations, the last mile represents one of the most critical functions in retail supply chains (Wang et al. 2020)

Although the last mile has become increasingly important, these home deliveries are the costliest channel in retailing (Lee and Whang 2001). They require individual picking, packing, shipping, and hand delivery of each customer order. Given this reality, last mile operations are comparatively time consuming, labor intensive, and inefficient (Lu et al. 2022, Praet et al. 2020). As an example, last mile delivery drivers spend an average of 9 minutes searching for an acceptable parking location in urban settings and walk nearly 8 km per day (Reed et al. 2022). Non-value-added activities like time delays, extra touches, and additional movements associated with last mile operations are expensive. Cost estimates of a single grocery delivery range between $10-$20 (Young 2023, Boyer et al. 2004). Other research suggests the last mile represents 28%-53% of overall delivery costs in retail supply chains (Cardenas et al. 2017, Yang et al. 2023, Lopez 2017, Wang et al. 2016). As these exemplars indicate, the last mile is a persistent financial headwind and ongoing operational challenge for retailers (Ha et al. 2020, Rao et al. 2014).

To address costly last mile problems, a number of operational techniques have been utilized. Optimization has improved delivery network design and subsequent routing efficiency (Liu et al. 2023, Fatehi et al. 2023, Rose et al. 2023, Lu et al. 2020). Changes to dispatching and scheduling procedures have also yielded gains (Agatz et al. 2011, Yang et al. 2016). Revenue management, pricing mechanisms, and auctions have helped reduce transportation costs (Wang et al. 2020, Agatz et al. 2013). Beyond these more traditional approaches, several innovations have also developed. Crowd sourcing has emerged from sharing economy business models to offer a unique last mile delivery option (He et al. 2023, Ta et al. 2020, Castillo et al. 2018). Centrally located pickup points have enabled customers to obtain deliveries via smart lockers and allowed retailers to consolidate shipments (Lyu et al. 2023, Castillo et al. 2020). Advanced drone and delivery robot technologies are similarly attempting to efficiently and effectively complete last mile operations (Tsai et al. 2021, Perera 2020). As these examples show, research into last mile delivery solutions is robust.

Beyond the direct cost implications of last mile inefficiencies, this channel also has adverse effects on society (Reed et al. 2022). From an environmental sustainability perspective, the last mile creates additional challenges through greenhouse gas emissions as well as the production and disposal of extra cardboard, plastic, or other packaging materials (Yang et al. 2023, Deng et al. 2021, Praet et al. 2020). In addition to these green considerations, last mile activities also have detrimental impacts on social sustainability in many communities. The high frequency of loading and unloading parcel shipments reduces traffic flow, creates congestion, extends transit times, and increases noise pollution (Qi et al. 2018, Reed et al. 2022; Cardenas et al. 2017). Perhaps most importantly, last mile operations create hazardous road conditions for other vehicles and safety issues for delivery drivers (Kiba-Janiak 2021). The negative externalities of the last mile are significant indirect costs in many retail supply chains.

Although meaningful last mile improvements have been made (Lim et al. 2022, Liu et al. 2023, Robinson et al. 2023) a fundamental problem still persists for retailers. Last mile operations require extra steps at the end of supply chains. Compared to other channel options, home delivery simply requires additional resources (Fatehi et al. 2023). It often takes more time, labor, equipment, movement, handling, energy, and packaging to complete the last mile. All those extras result in more cost and more adverse sustainability impacts (Praet et al. 2020). Optimization, process improvement, and innovation have certainly helped increase efficiency, but relative to other channel options, last mile will always carry higher costs. Given this operational reality, we now theorize a channel shifting behavioral alternative to address the growing last mile problem in retailing.

Social Exchange Theory

Social Exchange Theory (SET) provides insight into the formation, continuation, and dissolution of exchange relationships (Thibaut and Kelley 1959). It predicts that actors are more likely to trade with one another when relational rewards exceed the costs of exchange (Homans 1961). Relationship partners are selected based on comparisons of alternatives in terms of net costs and benefits (Kelley and Thibaut 1978, Blau 1964). However, evaluative criteria are broader than simple economic considerations. Social and psychological characteristics are also valid factors within a social exchange framework (Cook and Emerson 1978). Actors expect their contributions to be reciprocated by exchange partners to derive overall relational value (Gouldner 1960). When expectations are not met, relationships evolve or dissolve in the pursuit of more advantageous exchanges (Emerson 1976).

SET offers valuable understanding of how and why a customer selects a retailer for product purchases (Thomas et al. 2022). In this type of exchange relationship, a customer evaluates perceived costs and benefits of buying from a retailer. As part of that evaluation, the customer will likely consider the channel options a retailer provides. The convenience and ease of modern last mile delivery may appear beneficial to customers - especially when retailers increasingly do not charge a premium for direct to home shipments. At first glance, the rewards of last mile delivery appear unencumbered by other cost considerations. Common hassles like traveling to a retail location, navigating crowded store aisles, and waiting in checkout lines are avoided. The customer receives the product they desire from their preferred retailer without ever leaving the comfort of their home. Given only this information, SET logically predicts that many customers will select a last mile delivery channel.

Although last mile delivery is initially appealing to many customers, extant research suggests the channel produces harmful effects on the environment and the community (Deng et al. 2021, Praet et al. 2020, Kiba-Janiak 2021). We theorize that knowledge of negative sustainability externalities may alter customer channel selection decisions. If customers are made aware of the consequences of their delivery options, then their behaviors may change. Specifically, customers will select channels that are more neighborhood friendly and have lower carbon footprints. From a social exchange perspective, adverse impacts to society represent additional relational costs. In the absence of additional benefits to offset sustainability costs, customers are more likely to select a more beneficial channel option.

Sustainability Disclosures

Tangentially related areas of research support the notion that customer awareness of sustainability consequences generally impacts their purchase decisions. In the food labeling literature, scholars have repeatedly shown that explicit information about product sustainability alters perceptions and buying decisions (Majer et al. 2022). From cereal and coffee to meat and chocolate, multiple studies have demonstrated that labeling affects attitudes, satisfaction, price sensitivity, and purchase intentions (Bradu et al. 2014, Bauer et al. 2012). Similar labeling effects have been found in non-food categories like plywood, clothing, and laptop computers (Bernard et al. 2013, Majer et al. 2022). Across this diverse range of product types, empirical evidence indicates that many customers do not immediately consider sustainability attributes when making purchases. However, once they are provided with sustainability information, customer decisions are altered. When viewed through a SET lens (Thibaut and Kelley 1959), product labels provide customers with additional information so they can more thoroughly evaluate the costs and benefits of their exchange relationship options.

In addition to the labeling literature, research is starting to emerge regarding sustainability disclosure effects on ecommerce. Rai et al. (2021) provided empirical evidence that customers are willing to accept longer home delivery lead times on their purchases when they were told it would reduce carbon emissions. Thomas et al. (2022) showed that faster delivery time preferences could also be altered via different types of CO2 messaging to customers. Agatz et al. (2021) found green labels can influence grocery delivery time window selection decisions. Ignat and Chankov (2020) evaluated the delivery time preference effects of CO2 emissions and delivery driver working condition disclosures. As these exemplars demonstrate, the vast majority of customers (80%) do not inherently consider or understand the negative sustainability impacts of the last mile (B2C Europe 2018). However, when informed about sustainability externalities, customer decision making changes.

Hypotheses

Prior research has shown that customer preferences for delivery lead times and time slot appointments can be influenced by explicit sustainability messaging, but these modified customer behaviors still do not bypass the additional touches and movements associated with last mile operations. Thus, we theorize a novel channel shifting approach that nudges customers away from last mile deliveries towards lower cost store pickup. To accomplish this goal, and alleviate last mile volumes, we leverage the sustainable labeling literature and formal insights from SET. In particular, we emphasize the most immediate and salient sustainability externalities. Additional CO2 emissions as well as plastic and cardboard packaging waste of last mile deliveries are higher environmental costs of exchange relationships that customers want to avoid. Likewise, issues of congestion, noise pollution, and safety represent social sustainability costs that customers also do not want to incur. By explicitly educating customers on the largely unknown sustainability consequences of their channel decisions, we hypothesize the following channel shifting outcomes:

- H1: Providing an environmental sustainability label on ecommerce platforms shifts customer volume from last mile to store pickup channels.

- H2: Providing a social sustainability label on ecommerce platforms shifts customer volume from last mile to store pickup channels.

METHODOLOGY

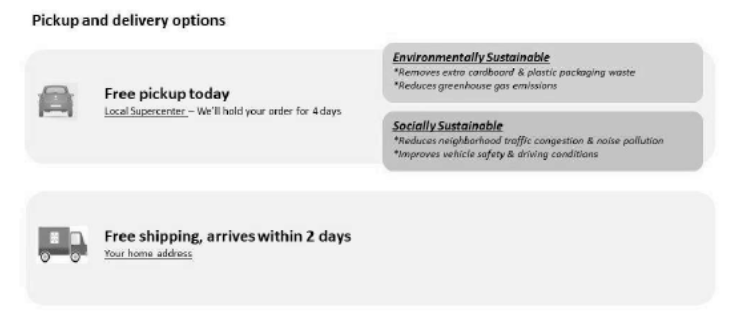

To test our hypotheses, we conducted a vignette-based experiment. Participants were asked to read a scenario about making a purchase with a retailer through their website and then presented a series of questions to assess their delivery channel preference, along with key outcomes such as their purchase satisfaction and repurchase intention. When participants were asked to make their delivery channel selection, (free same-day store pickup vs. free 2-day home delivery), they were exposed to two manipulated factors. The first was the presence or absence of a message regarding environmental sustainability. This message highlighted the fact that the store pickup channel saves packaging waste as well as greenhouse gas emissions. The second factor was the presence or absence of a message about social sustainability. This message called attention to the reduction in traffic (and related social benefits) associated with store pickup. Thus, our vignette was structured as a 2 (Environmental sustainability message: Present vs. Absent) x 2 (Social sustainability message: Present vs. Absent) full factorial design, creating four treatment conditions. Exact copies of our experiment treatment conditions are provided in Appendix A.

Vignette Considerations

The product we asked participants to imagine shopping for in our experiment was a new coffee maker. This product was selected for multiple reasons. First, coffee has wide appeal. About 75% of people in United States over the age of 20 consume coffee, and consumption is common across factors such as sex, education, and income (Loftfield et al. 2016). As a result, a coffee maker is something that the majority of participants have likely purchased and/or could see themselves purchasing. Second, there are a wide range of coffee makers available in terms of price. While something like a laptop computer (also with broad usage and appeal) is almost always an expensive, infrequent purchase, there is a make/model of coffee maker in the marketplace for every budget, meaning that the majority of participants could afford one and could purchase one without significant planning and saving. (Note: we did not specify the price of the coffee maker in the experiment for this reason, allowing participants to imagine something reasonable for themselves). Finally, a coffee maker could be purchased for a wide variety of reasons, including individual use, as a gift, to serve a daily utilitarian purpose, or as a hedonic indulgence. We wanted to control for (i.e. eliminate) any perceived sense of urgency in the experiment so we instructed participants that they were simply shopping for the purpose of acquiring a more up-to-date model. The nature of this product makes this scenario detail all the more conceivable.

Another noteworthy feature of our experiment design involves the scenario being set with a specific retailer, Walmart.com. We built this into the design for several reasons. First, it allowed us to present participants with a highly realistic shopping scenario as opposed to an unknown, generic, or fictitious retailer. We used several elements from the Walmart.com webpage in our vignette, including the two delivery channel options. The trade-off, of course, is that each individual has a preexisting disposition toward Walmart, (or any given retailer), that could shape their responses. We control for this by measuring participants shopping frequency with Walmart, (both online or in-store).

However, the main reason we decided to set the scenario with Walmart is because of the importance of controlling for travel time to a store location when examining participants’ delivery channel selection. When deciding whether or not to opt for store pickup vs. home delivery, the time required to get to a store location has been shown to play a significant role (Akturk and Ketzenberg 2022). Therefore, obtaining a valid assessment of the impact of sustainability messaging on channel selection would not be possible without accounting for this. While one could attempt to address this by specifying a travel time to the nearest location of a hypothetical retailer, another problem is encountered. For any stated travel time, some participants would find it normal, while others would find it unusual. Fifteen minutes, as an example, might seem perfectly normal to someone in a suburban setting while seeming long to someone in an urban environment and unrealistically short to someone in a rural community. Thus, creating a realistic hypothetical situation for all participants would be impossible. However, recent reports found that that 90% of the US population lives within 10 miles of a Walmart store (Walmart 2019), and that 95% of US households shopped at a Walmart store in 2023, (Reuter 2024). By specifying Walmart as the retailer, we include a store with which most every participant is likely to be familiar, and by asking each individual to report the typical commute time to the nearest Walmart store location, we are able to control for this issue when examining channel selection behavior. All this serves to maximize realism for those who participated in the experiment while achieving our intended control.

Participants

We recruited 200 participants for our experiment through Prolific Academic, an online labor market for academic research. All participants had to be located in the United States and report shopping online at least once every few months. In addition, each participant had to have submitted at least 10 studies prior to ours and have a lifetime approval rate of 95% or better. Qualified individuals were able to see a description of our study and, if interested, choose to participate. Upon doing so, they were provided a link to our experiment, built in Qualtrics, and paid $1.20 each for completion.

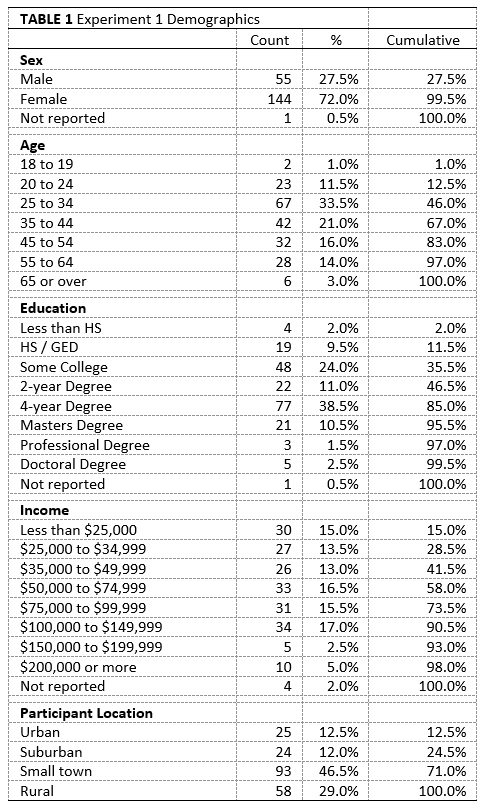

Several additional measures were taken to ensure the quality of the responses we received. First, understanding check questions were included after presentation of the scenario to verify that all respondents thoroughly read the details of hypothetical shopping situation before giving responses to questions of interest. Participants could not advance until all checks were answered correctly. Next, using graphics and page breaks, we designed the survey portion of the experiment to avoid long, uninterrupted series of Likert type questions which can lead to mindless responses. In addition, we polled participants at the end of the experiment regarding perceptions of realism. Specifically, we asked the degree to which they found the webpage snapshot and the shopping scenario to be realistic. Means to both questions in all four conditions were excellent, ranging from 5.32 to 6.26 (out of 7.0). Further, we examined response times and attention check questions for evidence of “speeding” or “cheating” (Smith et al. 2016; Schoenherr et al. 2015). All 200 participants correctly responded to the attention check question (e.g. “Please click Disagree if you are reading this”) that was included in a bank of Likert questions. In addition, we scrutinized the response of any participant who recorded an experiment completion less than half of the median time. This flagged 10 participants; however their multiple choice responses were internally consistent and showed no sign of “straightlining” or “Christmas treeing” (Smith et al. 2016), and they also provided sensible answers to the open-ended questions. As a result, all 200 responses were included in our analysis, yielding 50 participants in each of the four treatment conditions. Table 1 shows a summary of the relevant demographics.

Measures

After reading their randomly assigned vignette, participants responded to a series of survey questions to gage their intended behavior and sentiment. This research is designed to explore delivery channel preference shifting, so as a dependent variable, we collect data on customers’ delivery channel selection. This was captured as a binary choice between free two-day home delivery and free store pickup. We also want to determine if a retailer’s attempt to shift shoppers’ delivery channel selection has any unintended effects on customer perceptions and behavior. Therefore, we collect data on several additional dependent variables. First, to examine the short-term customer experience, we measure satisfaction in the current purchase scenario. Second, to examine possible impacts on future behavior, we also measure re-purchase intentions for future exchanges. Both purchase satisfaction and repurchase intention were each measured with a single item on a 7-point Likert scale.

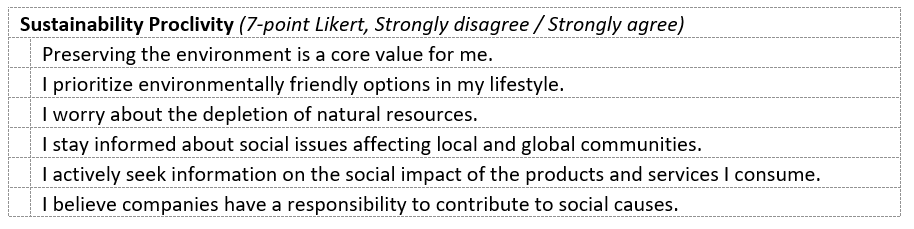

To determine the boundary conditions of when online sustainability labels lead to advantageous customer channel shifting, we also propose collection and measurement of several non-focal independent variables that may also affect customer decisions. First, given that the focal independent variables in this research are online sustainability labels, it is important to control for the pre-existing sustainability proclivity of experiment participants. This is measured with six items adapted from Milfont and Duckitt (2010) and Etheredge (1999) (See Appendix B). Next, we collect data regarding participants’ community type (e.g. urban, suburban, small town, or rural) and how many minutes (self-reported) it takes to arrive at their local Walmart store. Finally, SET suggests that perceived relational costs and benefits may vary across different customer segments. Therefore, demographic variables such as age, gender, and income are collected.

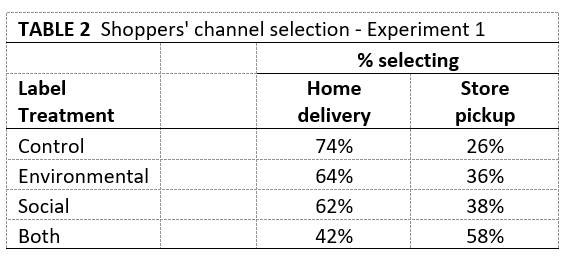

RESULTS

Descriptive statistics suggest that the sustainability labels indeed impacted shoppers’ choices of delivery channel. Table 2 below shows that when no labels were presented with channel options, only 26% of shoppers selected home delivery. However, the presence of sustainability-oriented labels appears to have caused a much greater proportion to select this preferred channel.

To analyze these results statistically, we utilized a logistic regression model due to the dichotomous nature of the delivery channel choice. We began with a model that included main effects of the two message types as well as their interaction. This model also included Age, Gender, Income, Shopping frequency with Walmart, and Time to nearest Walmart as covariates. However, neither the interaction term nor the covariates Age, Gender, Income, or Shopping frequency with Walmart were statistically significant. As a result, we remove these terms from the model to enhance parsimony and interpretability. The simplified model is statistically significant, (c2(3) = 21.39, p<0.001) and explains roughly 13.7% of the variance in the data (Nagelkerke R-Square). More tellingly, it is able to correctly classify 67.5% of shoppers’ channel selection. Both focal variables, environmental label and social label, contribute significantly to this task (p<0.05 respectively). Odds ratios show that environmental labels are associated with a 1.95 times greater chance of selecting in store pick-up, thus providing support for hypotheses 1. Similarly, social labels increase the odds of store pick-up by 2.05 times. This supports hypothesis 2. As for the time to Walmart covariate, it was statistically significant, (p<0.01), and greater commute times are associated with a slightly lower chance of shoppers selecting store pick-up, (odds ratio of 0.963), which makes intuitive sense.

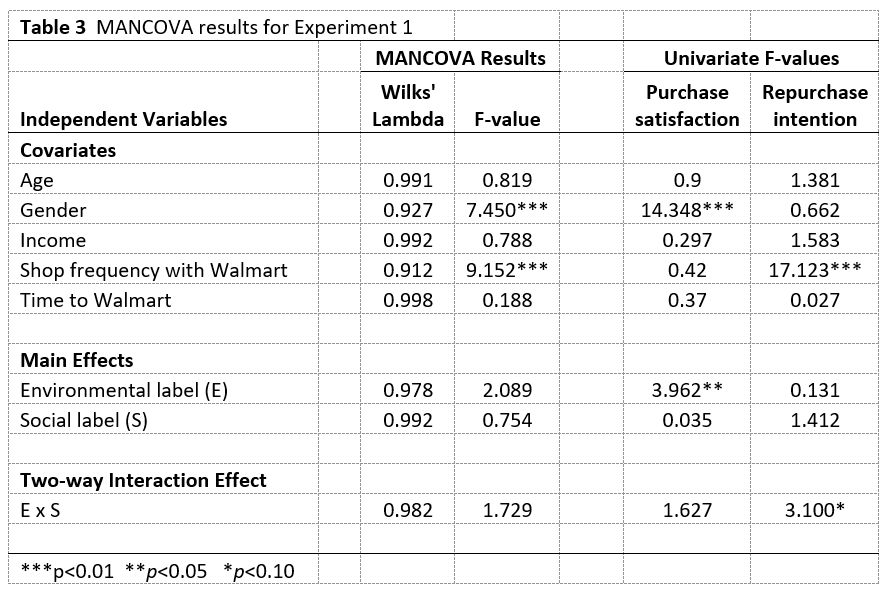

The remainder of our analysis is focused on the non-dichotomous dependent variables of interest, which include purchase satisfaction and repurchase intention. These were tested using a MANCOVA with environmental and social sustainability labels (and their interaction) as fixed factors, and the same set of control variables we employed in our first logistic regression model. Results are displayed in Table 3.

Focusing on the univariate results, purchase satisfaction was significantly affected

by the presence of an environmental label, (F1,192 = 4.036, p<0.05), though not a

social label. Estimated marginal means show that means were slightly higher when the

message was present than when it was not, (6.54 vs. 6.38). As for repurchase intention,

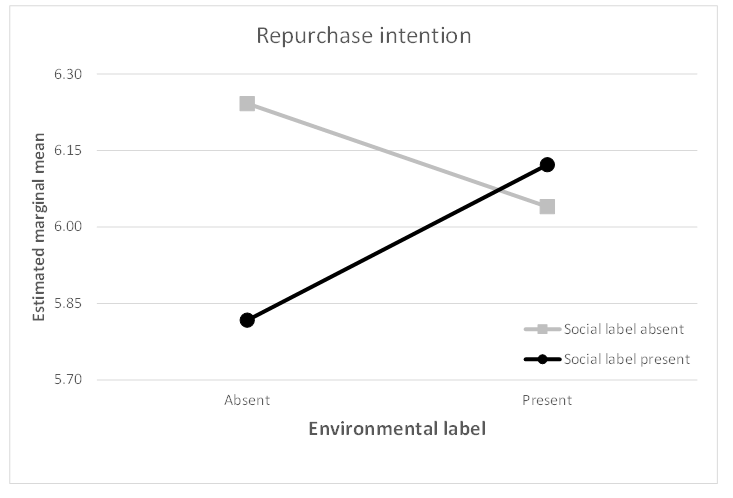

it was subject to a two-way interaction between the label types, (F1,191 = 3.10, p<0.10).

This interaction is depicted in Figure 1 below. While the interaction result was

above the conventional cutoff of p<0.05, (p=0.08 in this case), we proceed with interpretation

due to the strong impact of the Shop frequency with Walmart control variable. Current

shop frequency almost certainly affects repurchase intention, so the fact that the

interaction was able to approach statistical significance in the presence of this

control lends justification to its consideration.

FIGURE 1 Interaction effect

Results show that when no environmental label is presented, repurchase intentions are somewhat higher when no social message is presented either. However, when an environmental label is presented, repurchase intentions are fairly similar whether a social label is also presented or is absent.

Discussion

Results of our experiments indicate that sustainability labels are statistically and practically significant influences on channel selection decisions. When provided with environmental or social sustainability information about their channel options, customers will update their cost and benefit assessments in exchange relationships. As shown in Table 2, sustainability labels dramatically shift customers away from costly last mile deliveries. The logistics regression odds ratio suggests that explicit disclosure of negative externalities such as traffic congestion, vehicle safety, and noise pollution makes a customer twice as likely to select the store pickup option (Exp(B) = 2.05). Similarly, explicit disclosure of additional packaging wastes and energy consumption make store pickup selections nearly twice as likely (Exp(B) = 1.95). When both types of sustainability labels are implemented, in store pickup overtakes home delivery and becomes the more commonly selected channel. Perhaps most importantly, these cost reductions and sustainability gains did not adversely affect the customer experience. Customer satisfaction remained highly positive, and customers showed no substantive decline in their future purchase intentions.

To further explore the extent of the impact of sustainability messaging on channel selection, we developed a second, exploratory experiment. It is well-established that people respond to financial incentives. Discounting is another potential method that retailers could possibly employ in attempt to encourage store pickup, (e.g. $X.XX off your order if you pickup in store). We are curious as to how a sustainability labels compare to offering a financial incentive to shoppers in this context. Specifically, does a message have a greater or weaker impact than offering a shopper a monetary benefit for store pickup.

EXPERIMENT 2

Methodology

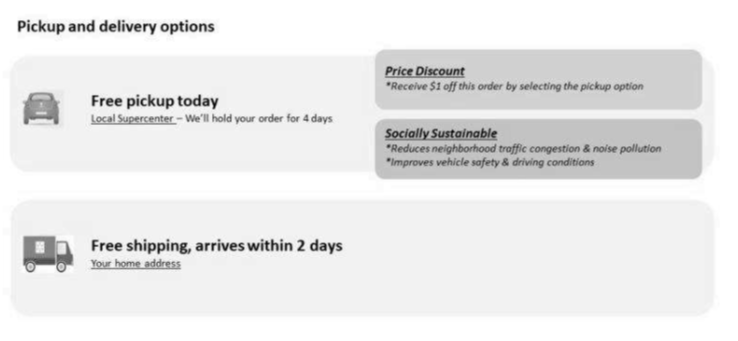

In Experiment 2, we introduce a price discount to incentivize channel shifting behavior. Inclusion of this independent variable not only enables interaction analysis, but it also provides a baseline measurement for comparisons with sustainability labels. The design of Experiment 2 is exactly the same as Experiment 1 except for one key feature. Instead of examining the impact of two different types of sustainability labels, we look at one label type (social), and the offering of a $1 dollar discount for selecting store pickup. In other words, Experiment 2 takes the form of a 2 (Social sustainability message: Absent vs. Present) x 2 (Discount: Offered vs. Not offered), full factorial design.

The social label was selected for consideration in this experiment due to the fact that in Experiment 1, there was little evidence of any substantive differences between social and environmental messages. Selecting only one allows for a simpler experiment. However, past research has shown that in a somewhat similar carrier selection context, social sustainability information was more impactful than environmental information in shaping decision makers’ selection in one-time transactions, (Davis-Sramek et al. 2018). As a result, we elected to focus on social labels. Next, a $1 dollar discount was selected based on industry practice. While discounts of up to $3 dollars were offered in attempt to get shoppers to accept slower delivery times during the peak of the Covid-19 induced e-commerce surge, those rates are more typically $1 to $2 dollars (Waters 2020). We focus on the smallest quantity in line with conventional practice as, from a retailer perspective, a smaller discount would always be preferable to a larger one.

Participants

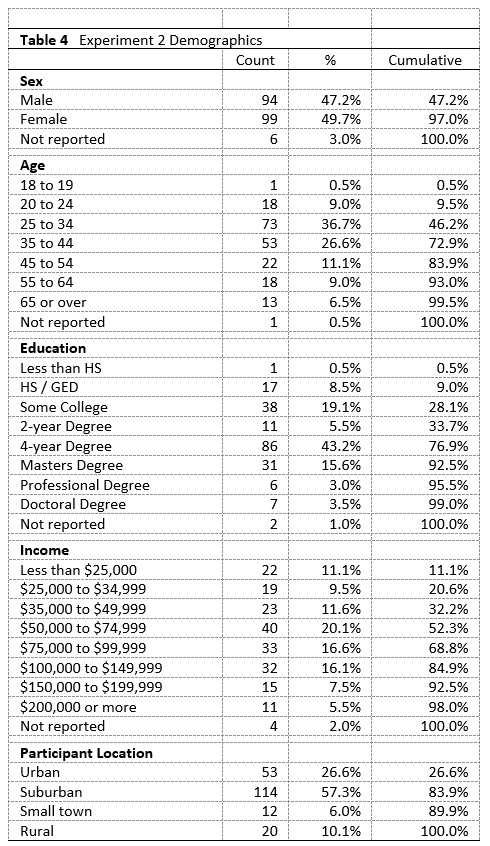

As in Experiment 1, we recruited 200 participants through Prolific Academic. All participants had to be located in the United States, report shopping online at least once every few months, have submitted at least 10 studies prior to ours, and have a lifetime approval rate of 95% or better. In addition, we excluded any individuals who participated in Experiment 1. Those who elected to participate and returned completed surveys were paid $1.20 each. Quality responses were ensured using the same techniques as in Experiment 1, including understanding checks, realism checks, attention checks, and an examination of response times. In this experiment, one participant was found to have failed the attention check question and provided questionable responses. Their data was removed from further analysis, leaving a sample of 199 participants. Table 4 shows a summary of demographics.

Results

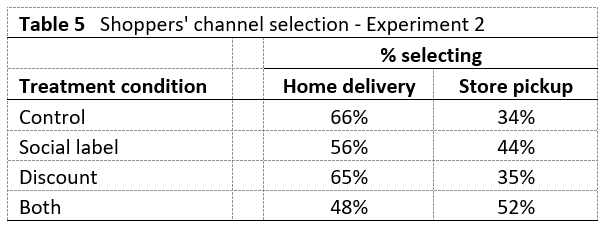

Descriptive statistics for delivery channel selection by condition are presented in Table 5. We test the significance of the treatments using a logistic regression model.

Our initial model included both treatment factors, their interaction, and Age, Gender, Income, and Time to nearest Walmart as covariates. None of the covariates were statistically significant, nor was the interaction between label and discount. To simplify the model and the interpretability of the results, these terms were all removed, leaving only the main effects of the focal factors as predictors. Results show that the model correctly predicts 59.8% of participants’ delivery channel selection and that the presence of a social sustainability label was associated with a 1.77 times greater chance of selecting store pickup, (unstandardized Beta weight = 0.57, SE = 0.29, Wald = 3.80, p = 0.05). This lends further support to hypothesis 2. The presence of a $1 dollar discount, on the other hand, was not statistically significant, (p>0.10).

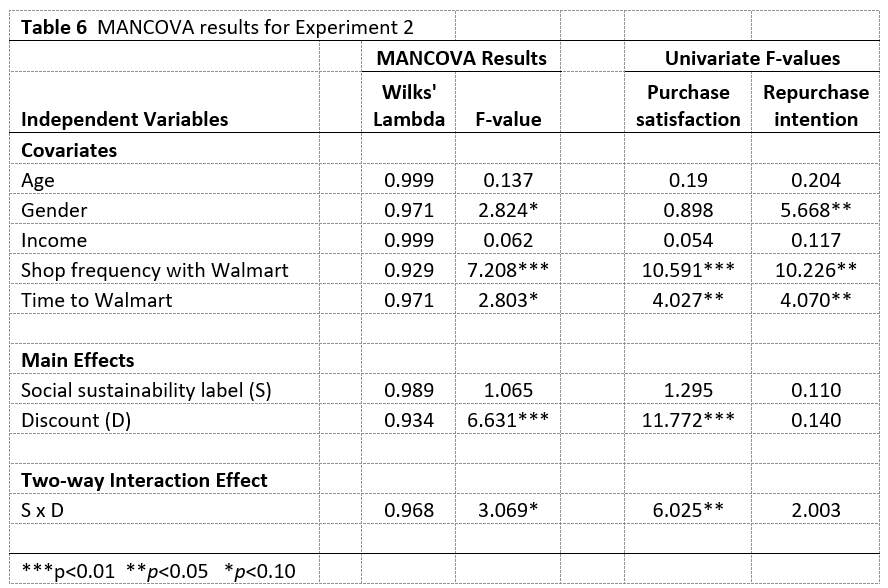

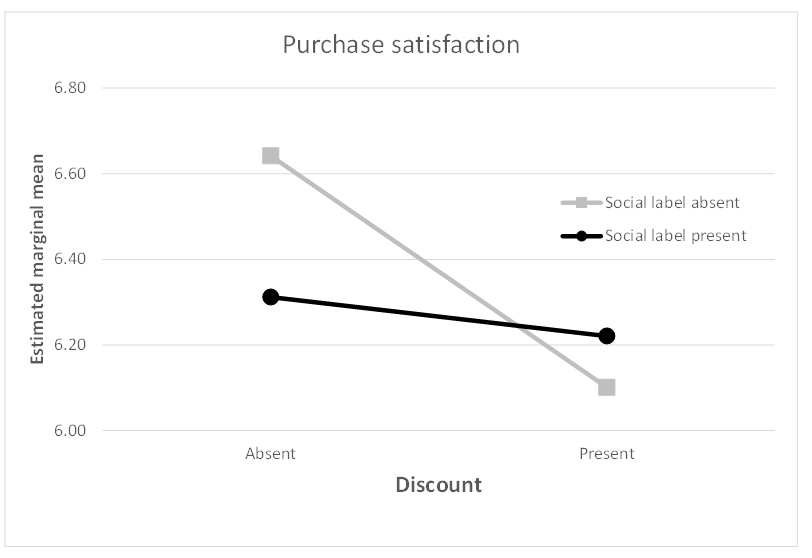

Turning attention to purchase satisfaction and repurchase intention, we run a MANCOVA as in Experiment 1. Results, displayed in Table 6, indicate a significant interaction between label and discount for purchase satisfaction, (F1,189 = 6.025, p<0.05) but that neither factor had an impact on repurchase intention.

The interaction, shown in Figure 2, indicates that when a social sustainability label is present, purchase satisfaction levels are relatively consistent regardless of whether or not there is a discount. In fact, offering a discount on top of the label hardly alters the mean satisfaction score. However, mean purchase satisfaction is highest when neither a label nor discount are presented to shoppers. This could indicate an adverse reaction to these nudging attempts, however mean scores are very desirable, (from a retailer’s perspective), regardless of the condition. Further, we find no evidence of impact, negative or otherwise, of the treatments on repurchase intention.

FIGURE 2 Interaction effect

Experient 2 Discussion

The robustness of ecommerce labeling effects was confirmed in our second experiment as explicit social sustainability information again nearly doubled customer propensity for store pickup over last mile deliveries. However, a $1 price discount did not have a significant effect on channel selection. This finding is interesting because price is often viewed as a primary determinant of customer decisions, but in this situation, the discount was not sufficiently compelling to alter channel selection. It is certain that if increasingly larger discounts were tried, eventually a value would be identified that was consistently effective at shifting channel selection, however this small amount, feasible to most large retailers, does not reach that level.

OVERALL DISCUSSION

Our findings provide evidence that shoppers can be “nudged” away from home delivery and toward store pickup through the presence of sustainability-oriented messages at the point of channel selection. This is consistent with past empirical evidence that shoppers are sensitive to sustainability disclosures and information when making purchases and last mile decisions, (Thomas et al. 2022, Agatz et al. 2021, Ignat and Chankov 2020). However, as previously noted, these studies focused on shifting preferences within the home delivery channel only, (namely lead times). To the best of our knowledge, our work is the first to demonstrate that shoppers can be effectively directed to an entirely different channel – particularly one that requires a lot more effort and involvement on their part. Further, our results show that this can be done without damaging purchase satisfaction or repurchase intentions. This has significant implications for retailers, who have tremendous incentives to see shoppers collecting purchases in stores as opposed to home delivery. The social, environmental, and economic costs are all clearly lower for the retailer, but having consumers go to a physical store increases the chances of the them setting foot inside, leading to additional purchases. Physical interaction with goods before purchase also reduces the chances of costly returns. As a result, our work informs retailers of a potential tactic for both cleaner and more profitable operations.

Managerial Implications

Last mile delivery is a costly operational challenge for retail supply chains. Although innovations and process improvements have driven some efficiencies in this area, it still represents the least profitable channel in retailing (Lu et al. 2022, Praet et al. 2020). However, results of this research show that sustainability labels, presented alongside delivery channel options, can shift shoppers’ behavior such that a significant portion of last mile deliveries are eliminated. By shifting volume to store pickup, retailers dramatically reduce unnecessary handling and movements of customer orders. Removing these extra activities from the end of the supply chain reduces costs and improves margins. Perhaps more importantly, these operational and financial gains do not adversely impact customer satisfaction or repurchase intentions. When informed about supply chain sustainability implications of their decisions, a significant segment of customers appear willing to change channels and continue to shop with the retailer in the future.

Beyond driving down last mile delivery costs, channel shifting also improves critical aspects of environmental and social sustainability. Last mile operations create excess cardboard, plastic, and packaging wastes that end up in landfills. Likewise, individual home deliveries consume more energy thus increasing a retailer’s carbon footprint. In addition to these green considerations, the stop and go necessity of delivery trucks contributes to traffic delays and congestion. They also create noise pollution and unsafe driving conditions for community members. However, channel shifting substantially reduces these burdens. By explicitly educating customers on sustainability externalities of their channel selection decisions, retailers can simultaneously improve critical aspects of performance for people, the planet, and profit. Such triple wins are quite valuable and too rare in actual retail practice.

The managerial implications of our novel channel shifting approach offer immediate cost savings and sustainability improvements, but they also potentially offer a profound strategic advantage for omnichannel retailers. Our research suggests that implementing sustainability labels in online platforms gets customers to leave the comfort of their own homes and come to a physical retail location to complete their shopping journeys. By educating customers on the sustainability externalities of the last mile delivery channel, consumption patterns change as customers come back to stores. Such a change benefits brick and mortar retailers, but it can adversely impact pure online retailers like Amazon. If a significant portion of large retailers like Walmart, Target, Costco, Home Depot, and Lowe’s collectively made efforts to expose the environmental and social sustainability problems of home delivery, they could drive sustainability conscious customers away from Amazon and pick up incremental sales opportunities via more profitable and more sustainable store channels. Our channel shifting approach may provide a significant competitive advantage for traditional store-based retailers and reshape less sustainable last mile delivery trends.

Academic Contributions

Extant literature on last mile delivery is robust and continues to grow. It has a primary focus on cost reduction via operational improvements like process changes, optimization techniques, and innovations. However, the literature lacks behavioral approaches that address last mile challenges. Our research makes a unique contribution to this important area of study. By theorizing and testing a novel channel shifting approach to the last mile problem, we are able to show that retailers can change customer channel selection decisions in meaningful ways that reduce the burden of home deliveries. A growing number of customers value supply chain sustainability and channel shifting leverages this trend. Our results indicate that combining environmental and social sustainability labels can potentially reduce last mile deliveries (and their corresponding costs) by over 40%. Thus, in addition to creating a new approach to address last mile concerns, our research also provides one of the most impactful cost saving options in the literature.

Beyond contributions to the last mile body of knowledge, this research also has implications for sustainability scholarship. With obvious improvements to packaging wastes, energy consumption, noise pollution, and vehicle safety, it broadens the scope of sustainable labeling effects. The current literature shows customer affinity for environmentally sustainable products as well as delivery time modifications. Our research builds on these findings in two ways. First, it extends labeling effects to include key aspects of social sustainability rather than only environmental concerns. Second, by affecting yet another critical aspect of consumption, this research shows that sustainable labeling also influences channel decisions. This previously overlooked outcome variable can improve overall supply chain sustainability.

From a social exchange perspective, our findings offer several nuanced insights into this formal theory. First, this research shows that cost and benefits of a relationship extend beyond product characteristics or personal interactions. The product delivery mechanism and corresponding sustainability effects matter in a modern omnichannel ecosystem. Customers not only evaluate which retailer to exchange with, but they now evaluate the channel of exchange within their chosen relationship. Second, our results show that social sustainability appears to have a greater effect on channel shifting decisions than environmental externalities. This finding may suggest that customer perceptions of exchange costs have a temporal element. The social sustainability costs in this research were more immediately experienced by participants. Whereas environmental issues are often less direct in the short-term and accrue over time. Third, the non-significance of a price discount relative to a sustainability label lends additional support to the strength of social and psychological factors in exchange relationships. The primacy of economic variables for customer decisions in modern retail supply chains is now more complex than previously conceptualized. The secondary channel evaluation, time phased cost considerations, and economic incentive efficacy add refined extensions to social exchange theory insights.

In the recent past, customer satisfaction and loyalty where enhanced by last mile deliveries (Ta et al. 2023). Retail patrons valued the ease of having packages placed on their doorsteps with an online mouse click. However, channel shifting seems to maintain satisfaction and loyalty levels for customers who choose store pickup when sustainability externalities are more thoroughly understood. We are encouraged by these results because they indicate customers may be more willing to consider non-economic factors when making purchase decisions. Furthermore, it shows that a growing customer segment is willing to exert more time and effort to impact sustainability. Such choices are notable because previous research has shown many customers want sustainability as long as it does not inconvenience them (Thomas et al. 2022). Perhaps some customers have reached a tipping point where supply chain sustainability is beginning to outpace logistics service quality considerations in omnichannel retailing. Such a change is welcome when the more sustainable option is also the lower cost option. Both retailers and customers win with channel shifting.

Policy Implications

Results of this research have implications for public policies designed to achieve environmental and social sustainability goals. In particular, our results suggest that a growing customer segment values sustainability and is willing to exert additional personal efforts to help society. However, customer decisions in this regard require explicit sustainability labeling in ecommerce exchanges. Most customers are either unaware of the negative externalities of last mile operations or choose to ignore their reality, but their decisions change when they are presented with even a brief reminder of the potential consequences, such as packaging waste, energy usage, safety concerns, and traffic congestion. Thus, simple education techniques and reminders appear to be a viable approach to curbing some of the negative externalities associated with e-commerce. Lawmakers could benefit from these findings. Rather than implementing onerous regulations, such as packaging mandates (or bans), electric vehicle mandates, or hour of operation limitations for delivery vehicles – all with negative trade-offs and potentially unforeseen consequences for businesses and society, (Tokar et al. 2021), policy makers can potentially achieve the same goals without the downsides via a series of simple label requirements. (And mandates, in this case, are unlikely to even be necessary as market forces and the drive for cost efficiency are likely sufficiently motivating to retailers to embrace these labels on their own). Evidence is provided by the effectiveness of mandated labels in other industries, such as nutrition labels on food packages and menus to drive healthy dietary choices, or graphic photos on cigarette packages to reduce smoking (Netemeyer et al 2016; Andrews et al. 2014; Kees et al. 2014).

Limitations & Future Research

As one of the first behavioral approaches to combat the high cost of last mile deliveries, this novel research represents an early attempt to validate channel shifting potential for omni-channel retailers. These results are encouraging, but we recommend several areas of future research that could expand the scope of knowledge in this emerging domain. First, evaluation of different product types is warranted. Would higher or lower involvement items that require differing levels of customer involvement affect results? Second, the lead times on last mile deliveries vary and require further investigation. How would a 1-day vs. a 1-week lead time on home delivery impact channel shifting proclivities? Third, analysis of market basket characteristics seems necessary. Are single item sales more or less prone to channel shifting than purchase bundles of multiple items? Fourth, consideration of multiple price discount levels is needed. At what point do pricing discounts have an effect on channel shifting and is that tipping point less than the cost of a home delivery? Finally, generalizability of experimental designs is always a methodological limitation (McGrath 1982). Ongoing programmatic research in this area is needed to build external validity for channel shifting concepts. We think these future research opportunities will address the inherent limitations of our initial studies in this fledgling, but vitally important, area of inquiry.

REFERENCES

Agatz, N., Campbell, A., Fleischmann, M., Savelsbergh, M. (2011). Time slot management in attended home delivery. Transportation Science, 45(3), 435-449.

Agatz, N., Campbell, A., Fleischmann, M.,Van Nunen, J. (2013). Revenue management opportunities for Internet retailers. Journal of Revenue and Pricing Management, 12(2), 128-138.

Agatz, N., Fan, Y., Stam, D. (2021). The Impact of Green Labels on Time Slot Choice and Operational Sustainability. Production and Operations Management, 30(7), 2285-2303.

Andrews, J. C., Netemeyer, R. G., Kees, J., & Burton, S. (2014). How Graphic Visual Health Warnings Affect Young Smokers’ Thoughts of Quitting. Journal of Marketing Research, 51(2), 165-183.

Akturk, M., Ketzenberg, M. (2022). Impact of Competitor Store Closures on a Major Retailer. Production and Operations Management, 31(2), 715-730.

Bauer, H., Heinrich, D., Schafer, D. (2012). The effects of organic labels on global, local, and private brands. Journal of Business Research, 66(8), 1035-1043.

Bernard, J., Hustvedt, G., Carroll, K. (2013). What is a label worth? Defining the alternatives to organic for US wool producers. Journal of Fashion Marketing Management, 17(3), 266-279.

Blau, P. (1964). Exchang and Power in Social Life. J. Wiley & Sons.

Boyer, K., Prudhomme, A., Chung, W. (2009). The last mile challenge: Evaluating the effects of customer density and delivery window patterns. Journal of Business Logistics, 30(1), 185-201.

Bradu, C., Orquin, J., Thorgeson, J. (2014). The mediated influence of a traceability label on consumer’s willingness to buy labelled product. Journal of Business Ethics, 124(2), 283-295.

B2C Europe. (2018). The Future of Ecommerce Lies in Its Sustainability and Sociality. Green & Social Delivery Report. Brussels.

Cardenas, I., Borbon-Galvez, Y., Verlinden, T., Van de Voorde, E., Vanelslander, T., Dewulf, W. (2017). City logistics, urban goods distribution and last mile delivery. Competition and Regulation in Network Industries, 18(1-2), 22-43.

Castillo, V., Bell, J., Mollenkopf, D., Stank, T. (2021). Hybrid last mile delivery fleets with crowdsourcing: A systems view of managing the cost-service trade-off. Journal of Business Logistics, 43, 36-61.

Castillo, V., Bell, J., Rose, W., Rodrigues, A. (2018). Crowdsourcing last mile delivery: strategic implications and future research directions. Journal of Business Logistics, 39(1), 7-25.

Davis-Sramek, B., Thomas, R.W., Fugate, B.S. (2018). Integrating Behavioral Decision Theory and Sustainable Supply Chain Management: Prioritizing Economic, Environmental, and Social Dimensions in Carrier Selection. Journal of Business Logistics, 39(2), 87-100.

Deng, Q., Fang, X., Lim, Y. (2021). Urban consolidation center or peer-to-peer platform? The solution to urban last-mile delivery. Production and Operations Management, 30(4), 997-1013.

Duan, Y., Aloysius, J., Mollenkopf, D. (2021). Communicating supply chain sustainability: transparency and framing effects. International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management. 52(1), 68–87.

Emerson, R. (1976). Social exchange theory. Annual Review of Psychology, 2, 335-362.

Etheredge, J. (1999). The perceived role of ethics and social responsibility: An alternative scale structure. Journal of Business Ethics. 18, 51-64.

Fatehi, S., Wagner, M. (2022). Crowdsourcing last-mile deliveries. Manufacturing & Service Operations Management, 24(2), 791-809.

He, E., Goh, J. (2022). Profit or growth? Dynamic order allocation in a hybrid workforce. Management Science, 68(8), 5891-5906.

Homans, G. (1961). Social Behavior. Academic Press.

Ignat, B., Chankov, S. (2020). Do e-commerce customers change their preferred last-mile delivery based on its sustainability impact? International Journal of Logistics Management, 31(3), 521-548.

Kees, J., Royne, M.B., Cho, Y. (2014). Regulating Front-of-Package Nutrition Information Disclosures: A Test of Industry Self-Regulation vs. Other Popular Options. The Journal of Consumer Affairs, 48(1) 147-174.

Kelley, H., Thibaut, J. (1978). Interpersonal Relations: A Theory of Interdependence. Wiley.

Kiba-Janiak, M., Marcinkowski, J., Agnieszka, J., Skowronska, A. (2021). Sustainable last mile delivery on e-commerce market in cities from the perspective of various stakeholders. Sustainable Cities and Society, 71, 1-11.

Lee, H., Whang, S. (2001). Winning the last mile of e-commerce. MIT Sloan Management Review, 42(4), 54-62.

Lim, S., Wang, Q., Webster, S. (2022). Do it right the first time: vehicle routing with home delivery attempt predictors. Production and Operations Management, 32, 1262-1284.

Liu, S., Luo, Z. (2023). On-demand delivery from stores: dynamic dispatching and routing with random demand. Manufacturing and Service Operations Management, 25(2), 595-612.

Loftfield, E., Freedman, ND., Dodd, KW., Vogtmann, E., Xiao, Q., Sinha, R., Graubard, BI. (2016) Coffee Drinking Is Widespread in the United States, but Usual Intake Varies by Key Demographic and Lifestyle Factors. The Journal of Nutrition, 146(9), 1762-1768.

Lopez, E. (2017). Why is the last mile so inefficient. Supply Chain Dive.

Lu, S., Suzuki, Y., Clottey, T. (2022). Improving the efficiency of last-mile package deliveries using hybrid driver helpers. Decisions Sciences, 1-23.

Lu, S., Suzuki, Y., Clottey, T. (2020). The last mile: driver helper dispatching for package delivery services. Journal of Business Logistics, 41(3), 206-221.

Lyu, G., Teo, C. (2022). Last-mile innovation: The case of the locker alliance network. Manufacturing & Service Operations Management, 24(5), 2425-2443.

Masorgo, N., Mir, S., Hofer, A. (2023). You’re driving me crazy! How emotions elicited by negative driver behaviors impact customer outcomes in last mile delivery. Journal of Business Logistics, 44, 666-692.

Mayer, J., Henscher, H., Reuber, P., Fischer-Kreer, D., Fischer, D. (2022). The effects of visual sustainability labels on consumer perception and behavior: A systematic review of the empirical literature. Sustainable Production and Consumption. 33, 1-14.

McGrath, J. (1982). Dilemmatics: The study of research choice and dilemmas. Judgment Calls in Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Milfont, T., Duckitt, J. (2010). The environmental attitudes inventory: A valid and reliable measure to assess the structure of environmental attitudes. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 30, 80-94.

Netemeyer, R. G., Burton, S., Andrews, J. C., & Kees, J. (2016). Graphic Health Warnings on Cigarette Packages: The Role of Emotions in Affecting Adolescent Smoking Consideration and Secondhand Smoke Beliefs. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 35(1), 124-143.

Perera, S., Dawande, M., Janakiraman, G., Mookerjee, V. (2020). Retail deliveries by drones: will logistics networks change? Production and Operations Management, 29(29), 2019-2034.

Praet, S., Martens, D. (2020). Efficient parcel delivery by predicting customer locations. Decision Sciences, 51(5), 1202-1231.

Qi, W., Li, L., Liu, S., Shen, Z. (2018). Shared mobility for last-mile delivery: design, operational prescriptions, and environmental impact. Manufacturing & Service Operations Management, 20(4), 737-751.

Rao, S., Rabinovich, E., Raju, D. (2014). The role of physical distribution services as determinants of product returns in internet retailing. Journal of Operations Management, 32(6), 295-312.

Reed, S., Campbell, A., Thomas, B. (2022). The value of autonomous vehicles for last-mile deliveries in urban environments. Management Science, 68(1), 280-299.

Reuter, D. (2024). Walmart's average customer is a suburban baby boomer who spent $3,578 there last year. Retrieved from: https://www.businessinsider.com/walmart-typical-customer-demographics-shopper-profile-numerator

Robinson, P., Sahin, F., Gao, L. (2023). Network design with consideration of hours of service regulation and drop and swap trailer operations. Decision Sciences, 1-18.

Rose, W., Bell, J., Griffis, S. (2021). Inductive research in last-mile delivery routing: introducing the re-gifting heuristic. Journal of Business Logistics, 44, 109-140.

Schoenherr, T., Ellram, L.M., and Tate, W.L. (2015). A Note on the Use of Survey Research Firms to Enable Empirical Data Collection. Journal of Business Logistics, 36(3), 288-300.

Ta, H., Esper, T., Hofer, A., Sodero, A. (2023). Crowdsourced delivery and customer assessments of e-Logistics service quality: An appraisal theory perspective. Journal of Business Logistics, 44, 345-368.

Thibaut, J., Kelley, H. (1959). The Social Psychology of Groups. Wiley.

Thomas, R., Murfield, M., Ellram, L. (2022). Leveraging sustainable supply chain information to alter last mile delivery consumption: A social exchange perspective. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 34, 285-299.

Tokar, T., Jensen, R., Williams, B.D. (2021). A guide to the seen costs and unseen benefits of e-commerce. Business Horizons, 64, 323-332.

Tsai, Y., Tiwasing, P. (2021). Customer’s intention to adopt smart lockers in last-mile delivery service: A multi-theory perspective. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 61, 1-9.

Walmart (2019). America at work: A national mosaic and roadmap for tomorrow. Retrieved from: https://corporate.walmart.com/content/dam/corporate/documents/press-center/automation-is-reshaping-work-across-america-a-new-report-explores-the-impact-and-how-communities-might-respond/walmart-america-at-work-report-online-compressed.pdf

Wang, L., Rabinovich, E., Guda, H. (2020). An analysis of operating efficiency and policy implications in last-mile transportation following Amazon’s integration. Journal of Operations Management, 69, 9-35.

Wang, Y., Zhang, Q., Liu, F., Shen, L., Lee, H. (2016). Towards enhancing the last-mile delivery: An effective crowd-tasking model with scalable solutions. Transportation Research: Part E, 93, 279-293.

Waters, M. (20200 Why retailers like Amazon and Target are embracing no-rush delivery. Retrieved from: https://www.modernretail.co/retailers/why-retailers-like-amazon-and-target-are-embracing-no-rush-delivery/

Yang, H., Fang, M., Yao, J., Su, M. (2023). Green cooperation in last-mile logistics and consumer loyalty: An empirical analysis of a theoretical framework. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 73, 1-12.

Yang, X., Strauss, A., Currie, C., Eglese, R. (2016). Choice-based demand management and vehicle routing in e-fulfillment. Transportation Science, 50(2), 473-488.

Young, S. (2023). Retailers Set Higher Bars for Free Shipping as Delivery Costs Surge. The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/retailers-set-higher-bars-for-free-shipping-as-delivery-costs-surge-3c8b9a39.

Appendix A: Experiment

Scenario

Please imagine yourself in the following shopping scenario:

You would like to get a new coffee maker. Your current one works fine, but you are interested in buying something with a more contemporary look and up-to-date features.

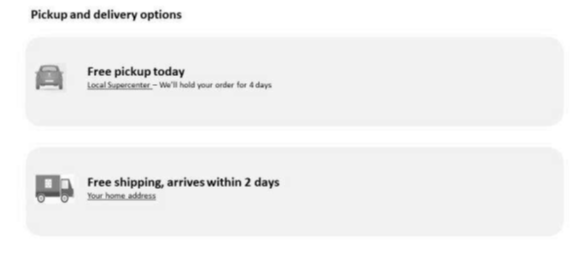

(Control Condition – Experiments 1 and 2)

After a thorough search for coffee makers, you find the exact one that you are looking for on the Walmart.com customer website.

(Note: the researchers conducting this survey are not affiliated with Walmart in any way. The company is simply being used as an example in this scenario)

You add the item to your cart and begin to checkout. You are then presented with the following pickup and delivery options:

Which pickup or delivery option would you select for your coffee maker purchase?

o Free pickup (today)

o Free shipping (2 days)

(Both Social and Environmental Label Condition – Experiment 1)

Which pickup or delivery option would you select for your coffee maker purchase?

o Free pickup (today)

o Free shipping (2 days)

(Social and Discount Condition – Experiment 2)

Which pickup or delivery option would you select for your coffee maker purchase?

o Free pickup (today)

o Free shipping (2 days)

Appendix B: Measurement Scales