Digital Health Passes: It’s Not the Technology but the Ecosystem That Matters

June 3, 2021 | By Erran Carmel and Mary Lacity

While most Americans who want a Covid-19 vaccine can get one, proving you’ve been vaccinated remains problematic. The paper cards provided by the Center for Disease Control (CDC) are easily forged, and very few systems can verify that you have received the shot(s). The situation isn’t much better in other parts of the world, where millions of shots were given without collecting adequate identification to validate their vaccination status.

International travel may become the lever that forces the coercive adoption of Digital Health Passes (DHPs) all over the world. The next time you pack your passport to cross an international border (even the U.S.-Canada border), you may also be required to download a DHP to your phone that shows your coronavirus vaccination and/or a recent COVID-19 test result.

The purpose of DHPs is laudable: they aim to protect public health so we can all return to travel, work, school and play in relative safety.

How close are we to the goal of protecting public health with DHPs? To answer that question, we have been interviewing DHP leaders and decision makers at technology companies, organizations bringing workers back to the office, standards-making communities, and airports, as well as individual users.

The good news is you already can download DHP “wallets” into your smartphones. The wallets we evaluated are designed to protect privacy and to secure data. Most American DHPs subscribe to ethical principles (for example, the Good Health Pass) and comply with regulations for privacy protection. Many DHPs, such as IATA’s Travel Pass and IBM’s Digital Health Pass, use blockchain technologies to create tamper-resistant records.

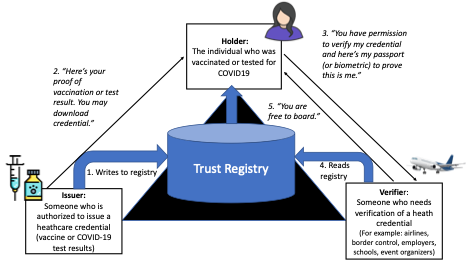

The bad news is that some first generation DHPs are little more than illusions of public safety because the underlying ecosystems have not yet connected the three key stakeholders. Ideally, as in the diagram below, a DHP should collect and confidentially share information within a “trust triangle” ecosystem comprised of the health-care providers (issuers), individuals (holders) and the institutions (verifiers) that need to verify an individual’s health credentials.

Some DHPs are just digital versions of self-reports, where users claim, “Yes, I feel fine today,” and then their DHP flashes an official-looking green signal of health to employees guarding entrances. Or the institution needing to verify someone’s health accepts a DHP credential but fails to verify that the person flashing a DHP on a mobile is the actual person with the health-care credential (called identity binding). Or the institution has no way to scan the DHP to run an independent verification against the health care data registry. Or the DHP may be connected to a single health-care provider like a major pharmacy, but no one other than the pharmacy accepts the DHP as evidence.

Jim St. Clair, Chief Trust Officer at Lumedic, added a further concern, “Perhaps most concerning is the growth of proposed verification solutions that allude to privacy but fail to provide users true privacy-by-design in ‘selective disclosure’ of health information.”

These early experiments with DHPs are generating valuable insights, and they will improve over time if we heed their lessons.

Since it is unlikely that universal standards will be adopted, each of us will have multiple DHP wallet apps on our smartphones, one for each ecosystem in which we must prove our health status. So for now, these early DHPs fall short of connecting and integrating the three parts of the trust triangle ecosystem.

Ideal “Trust Triangle” Ecosystem

In an ideal trust triangle ecosystem, only authorized issuers should issue health-care credentials to the trust registry (step 1) and then notify holders that their credential is available to them for use (step 2). Only individual holders should control who is allowed to read their health-care credentials and verify their status; individuals should also prove they are the holders of that credential (step 3). Verifiers, once granted permission by the holder, read the trust registry to verify validity of the credential (step 4) and notify the holder of the verification outcome (step 5).

As information systems professors, we understand it takes time for organizations to build new digital ecosystems and for people to embrace them. Think back to the early days of the Internet when Jeff Bezos first tried to sell books via Amazon. People thought the Internet was unsafe for payment transactions, but early adopters who risked a $10 book purchase provided the foundation for today’s US $4.8 trillion e-commerce market.

Similarly, we should welcome the DHP first generation, even if it falls short of ideal, provided it doesn’t come at the expense of personal privacy of health data. While the U.S. federal government has thus far failed to propel the DHP ecosystem, at least one U.S. state (New York) has stepped in with a DHP (Excelsior, which is built on the IBM platform). The pioneering citizens of New York teach us that government policy can spawn adoption: you are encouraged to have this DHP to enter Barclays Center in Brooklyn to watch NBA games. But the verification loop was not closed yet and for good reason: Imagine the thousands of people who enter the arena at the start of an event — what stadium has the capacity to scan a ticket, a DHP, and an ID to connect the three? And by what authority does the person at the turnstile have to deny anyone access?

For similar reasons, one airport director we interviewed opposed rapid COVID-19 testing in airports: “We are not health-care professionals … what do we do if someone tests positive? Kick them out of the airport and say good luck? Isolate them in the airport? Or do another test in case it was a false positive? How am I supposed to track results and comply with HIPAA?”

These and other sticky administrative issues show that we need more than the trust triangle to build the ecosystem. We’ll need a fourth point that turns the triangle into a diamond: A governing authority that defines rules, processes and compliance.

We now are quite certain that the pandemic will be with us for some years. Governments that want to protect their borders will erect hardened health walls. One piece of these walls is going to be DHP. To get there, we must be patient as early adopters stagger through the first generation. We cannot say how many generations until we get to the ideal DHP triangle/diamond. But it is conceivable that a DHP will be a staple of international travel before 2025.