Being the Bridge: Drop-Shipping and the New Terms of the Triad

November 15, 2019 | By Jeff. L. Wright and Ryan Sheets

Don’t you hate it when two-day shipping or ship direct to customer is not an option? Who has the time (or a big enough vehicle) for store pickup nowadays? As consumers, we only tend to focus on – or care about – what is convenient for us: are we getting the products when and how we want them?

This drive for convenience, however, puts great pressure on suppliers and manufacturers. In fact, it puts so much pressure on them that it can fundamentally remake the preexisting relationship between retailers and manufacturers.

The remaking of these relationships is the topic of Simone T. Peinkofer, Terry L. Esper, Ronn J. Smith, and Brent D. Williams’ 2018 article in the International Journal of Production Research, “Assessing the impact of drop-shipping fulfilment operations on the upstream supplychain.” In this research, they explain that the advent of the internet has not only changed the way customers shop, it has also greatly affected the upstream supply chain (in particular suppliers and manufacturers) by shifting dynamics in three-way (also known as triadic) relationships.

Drop-shipping is when a supplier or manufacturer (for example, Whirlpool) is shipping their product

directly to your home address at the request of a retailer (for example, any big box

retailer). In the past, these retailers served as the bridge between customers and the supplier or manufacturer. Customers also have had direct

access to many suppliers since the days of mail-order catalogues. At times, it seems

that drop-shipping pits partners against partners or at least complicates the normal

terms of their relationships.

Drop-shipping is when a supplier or manufacturer (for example, Whirlpool) is shipping their product

directly to your home address at the request of a retailer (for example, any big box

retailer). In the past, these retailers served as the bridge between customers and the supplier or manufacturer. Customers also have had direct

access to many suppliers since the days of mail-order catalogues. At times, it seems

that drop-shipping pits partners against partners or at least complicates the normal

terms of their relationships.

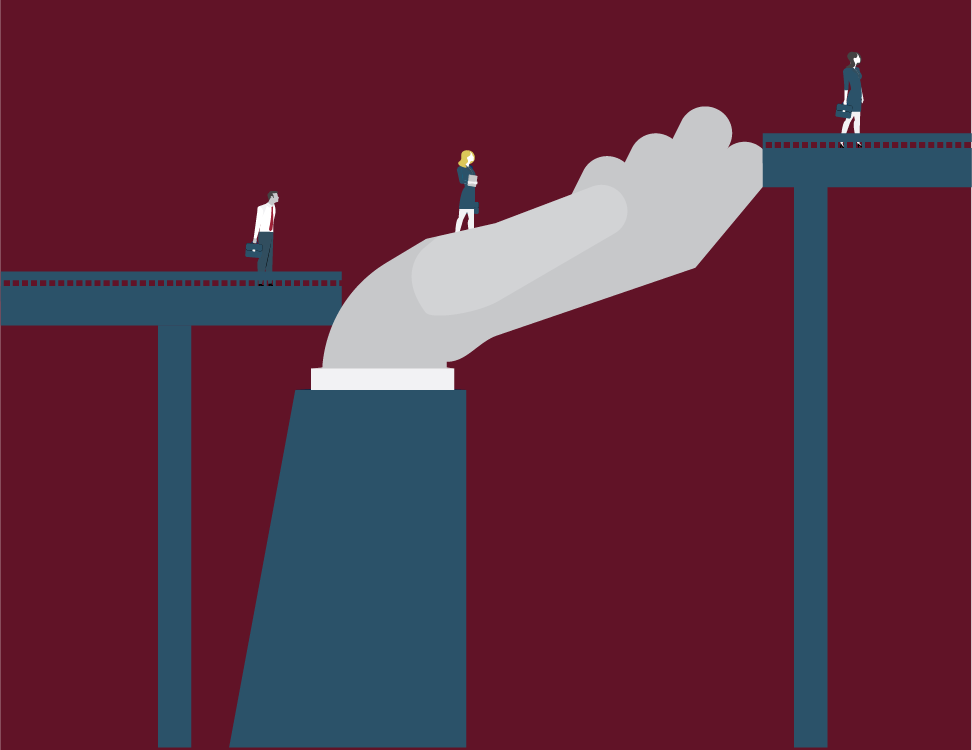

This raises questions as to how retailers have managed to remain in the bridge position in this three-way relationship, and what about that changes when suppliers attempt to take over services formerly provided by retailers? Most previous research on this supplier-retailer-customer relationship focused on retailers being the bridge. That kind of research explored the three-step nature of the supply chain without addressing changes and shifts taking place in direct-to-customer markets which largely have emerged because of internet sales. The article points out how heavily existing research had focused on definitions and semantics, primarily because even the term “triad” is starting to become questionable in the current marketplace where retailers may not even be part of the triangle anymore.

The Bridge Between Manufacturers and Suppliers

The classic triad had manufacturers and suppliers at one end of the spectrum with

customers at the other. The bridge between these two were the retailers. You need

a 2-inch wood screw, you go to the hardware store and buy a box of wood screws. The

retailer, as the bridge, had to buy a pallet of those boxes of screws from their supplier,

inventory them, store them, and stock the shelves. Storing a pallet of wood screws

is one thing, but this model changes drastically when you switch to washing machines,

refrigerators, and even automobiles that take up a lot of space and require a lot

of overhead to house and protect. This led retailers to demand that suppliers ship

these items directly to customers, a practice called drop-shipping.

The classic triad had manufacturers and suppliers at one end of the spectrum with

customers at the other. The bridge between these two were the retailers. You need

a 2-inch wood screw, you go to the hardware store and buy a box of wood screws. The

retailer, as the bridge, had to buy a pallet of those boxes of screws from their supplier,

inventory them, store them, and stock the shelves. Storing a pallet of wood screws

is one thing, but this model changes drastically when you switch to washing machines,

refrigerators, and even automobiles that take up a lot of space and require a lot

of overhead to house and protect. This led retailers to demand that suppliers ship

these items directly to customers, a practice called drop-shipping.

This eventually leads to some suppliers cutting out retailers and assuming the duties as their own bridge to the customer. While this may seem like a classic, retailers just shot themselves in the foot scenario, it turns out things are not so clear cut. When suppliers assume the responsibility for those bridge services, they leave room for some retailers to remain as the bridge. This wiggle room creates some logistical entanglements for suppliers who have tried to bypass retailers altogether. For example, if you need wood screws, you probably want to drive to the store and get some as opposed to having them shipped to you. Hardware stores, then, stay in the bridge position.

Customers have traditionally had to have items like refrigerators delivered to their home, either by the retailer or by the supplier shipping directly to the customer. Now, whoever houses and delivers refrigerators must both account for inventory going in and out and have a shipping operation to consider. Further exacerbating this situation is the fact that delivering a pallet of products to a retailer or a single unit to a customer’s home in a suburban neighborhood are not the same. So, right away we must acknowledge that it completely depends on what you are supplying and selling as to whether becoming the bridge would be beneficial to your operation. While it may seem logical for a supplier to shift to direct-to-customer sales and shipping in the age of internet commerce, the bridge services required by the end-consumer will determine whether this is viable for any individual company. Customers will not want to ship their cars back to Detroit to be repaired, yet at the same time they also may not want to have to deal with buying it at a car dealership. In such cases, the supplier/manufacturer might have to consider changing how warranties and services would shift if a car dealership were no longer involved.

New Meanings

The researchers used several terms that have either shifted in meaning or have adopted new meanings altogether. Omni-channel retailing represents some of the newer end-consumer services, such as in-store delivery/pickup. This additional channel to the operation may require companies to expand and/or add distribution centers or try to integrate it into their existing network. Additionally, the number of online sales can make or break this channel, with the potential to flood new and overwhelmed distribution centers or render those same centers a financial drain due to low sales. The researchers divide the literature and data on this channel into three streams.

The first stream focuses on the issue of drop-shipping and how it changes the bridge position. Drop shipping allows an online retailer to have fast and efficient fulfilment performance. This may come at a cost as the retailer is then in the position to be blamed for poor fulfilment by the supplier. The online retailer may see higher sales but may also take a loss on open-box returns.The second stream of literature suggested that online retailers better handle large, bulky items – refrigerators and cars – through drop-shipping. Other literature in this stream indicated that online retailers should explore a combination of owning inventory and drop-shipping various, hard-to-store products. While this may seem like one of those areas where suppliers and manufacturers could force retailers out, don’t forget about returns: a customer’s ability to ship a faulty or damaged refrigerator or washing machine back to a supplier is more limited than the supplier’s shipping capabilities. This factor alone constrains the bridge’s role and may make local retailers or distribution centers mandatory.

The third stream of literature suggested that retailers and manufacturers can offset losses through better communication and data sharing. Since retailers may be blamed for poor shipping fulfilment or product quality, they have implemented revenue sharing incentives to improve performance. The literature also indicated that openness about data in fluctuating ordering cycles led to improved relationships. So, explaining that people buy fewer wood screws when it’s freezing outside and they don’t want to work on their houses may lead to different and improved contractual agreements between retailer and supplier.

In terms of the supplier assuming the bridge operations, two themes emerged: rationalizing and integrating. Rationalizing the issues surrounding suppliers in the drop-shipping dynamic sometimes required acquiescing. Acquiescing refers to the strategies retailers and suppliers employ in regard to the power that retail customers can leverage over suppliers and/or retailers in this dynamic.

Acquiescing strategies might focus on how customers may need drop-shipping for large or uncommon items that they cannot retrieve from a retail store to pick up, like a refrigerator, a large item that consumers may only purchase once every few decades. Therefore, all parties involved must acquiesce to the customer’s demands in this case. Some suppliers are simply reacting to changes in the marketplace, such as a customer’s ability to order that refrigerator online through the supplier’s website. Suppliers can even customize products, like putting your name on your favorite color and flavor of candy covered chocolates. This can also lead to rationalizing penetration strategies into the marketplace, where suppliers may have greater potential to meet customer demands than retailers might, or vice versa.

Integrating these principles required various considerations and strategies. Suppliers who become the bridge face the challenge of scaling up. Suppliers’ compliance with retailer and end-consumer demands could further complicate this issue. This complexity leads to scaling challenges, such as whether the car manufacturer can also cover the duties of repairing drop-shipped cars under warranties. These challenges made integrating drop-shipping difficult because coordinating logistics can be difficult. Technology can greatly increase efficiency, but it also depends on whether external or internal coordination is required. For example, internal communication with a company’s IT department may be key in successfully implementing drop-shipping between supplier/retailer and the consumer. That said, if a physical internet is ever to be achieved, coordination with external shipping and trucking companies by those companies is crucial.

Managerial Implications and Balancing Ambidexterity

Ambidexterity describes the balancing of all of this and a company’s ability to utilize and exploit existing capabilities while also looking for new ways to meet customer demands. Our recent blog on Nordstrom’s and Ralph Lauren’s smart fitting rooms exemplify this ambidexterity. Both companies still have an online sales presence, while exploring and developing new technologies to cultivate customers for their brick-and-mortar operations by providing a lot of the online features in their in-store smart fitting rooms.

Drop-shipping is a necessity in today’s marketplace for several reasons. The question of who becomes the bridge in the supply chain remains unanswered. Suppliers and manufacturers may benefit from cutting out the retailer. They will, however, also assume all of that retailer’s responsibilities and any blame in the case of poor end-consumer shipping and quality fulfilment. One caveat is that retailer’s demands have put them at odds with suppliers in the past, and new strategies, such as revenue incentives, have had to be employed to alleviate some of these fulfilment stressors. Regardless of who assumes control of the bridge, coordination and communication will be key factors in the successful implementation of drop-shipping.