The Hypercompetitive World of Omnichannel Retail

November 6, 2020 | By Dinesh Gauri

I was sitting alone in my car in a Walmart parking lot while using my phone to compare retail prices and availability on a particular brand of toothpaste recommended by my dentist. Amazon had what I needed at about the same price as Walmart, and I could get it the next day with free delivery. So, I ordered it online and left without ever entering the store.

As a professor specializing in marketing, I would have loved to report that, at that moment, I’d made a connection to the research paper I had recently co-authored about the ongoing battles between retailers to extend their omnichannel reach into each other’s turf. In reality, I was mainly thinking about getting some relief for my extraordinarily painful toothache.

Later, when the throbbing in my head had subsided, I recognized how my experience

as a customer that day illustrated several of the points our research discovered about

the dilemmas retailers now face when it comes to expanding their customer bases. The

most vexing of those challenges is this: Figuring out how to play to the strengths

that helped create and build their brands, while at the same time strategically investing,

innovating, and pivoting into arenas that historically have been dominated by their

competitors.

Later, when the throbbing in my head had subsided, I recognized how my experience

as a customer that day illustrated several of the points our research discovered about

the dilemmas retailers now face when it comes to expanding their customer bases. The

most vexing of those challenges is this: Figuring out how to play to the strengths

that helped create and build their brands, while at the same time strategically investing,

innovating, and pivoting into arenas that historically have been dominated by their

competitors.

Much of the developed world has evolved into an omnichannel shopping environment where retailers exist both online and in physical stores and where technology is playing a greater and greater role in researching and making purchases. There’s a temptation for retailers to rush headfirst into the competition’s primary domain. But as Rupinder P. Jindal, Wanyu Li, Yu Ma, and I noted in a paper to be published in the Journal of Business Research, that approach doesn’t always align with the expectations or demands of customers.

To put it simply, Walmart has to keep being Walmart, even as it strives to win customers from Amazon by developing an improved online experience. And Amazon has to keep being Amazon, even as it adds physical stores (its own or with Whole Foods) in its attempt to win customers from traditional retailers like Walmart. The same is true, by the way, for Target, Best Buy, Costco, Sam’s Club, Lowe’s, Home Depot, and just about every other retailer in the marketplace.

Two Marketing Realities

The backbone of our paper is a survey of preferences and behaviors of more than 500 respondents that asked, among other things, the first thing that came to their mind when they heard the names of various retailers. For instance, Amazon brought to mind words like online, variety, convenient, everything, and free shipping. Walmart was described as cheap, low prices, good prices, affordable, and good. And Target was portrayed as expensive, variety, fun, quality, and good.

Changing such perceptions is a monumental, expensive, and risky proposition. It’s also largely unnecessary given two realities that strangely find a way to co-exist in the marketplace: The fundamentals of retail haven’t changed, while at the same time retailing is mirroring the tech industry. Both realities came into play, in fact, when I bought that tube of toothpaste.

The Unchanging Fundamentals of Retail

Shoppers continue to value the basics of good retailing – things like convenience, price, assortment, quality, in-stock availability, and reliability.

What’s changed in recent years is the leveling of the playing field on price. The proliferation of online options has made it more and more difficult for any retailer to have an advantage over another on the price of the same item, which means no retailer can afford to give ground in an area that has become table stakes to enter the game. Walmart’s “Everyday Low Prices” model, for instance, is far less of a competitive advantage now that many of the products it offers can be found at the same price or lower at Amazon or other online stores.

Assortment is the biggest advantage for large online players like Amazon, which features more than half a billion available items. Walmart has expanded its online assortment (and grown its online market share), but still lags far behind with roughly 15-18 percent of what’s found on Amazon.

While growing that assortment, Walmart has played to its strength of convenience and availability. Amazon’s convenience is in the quick, easy online experience, while Walmart gives customers far more options for in-store experience (for those who want to examine products in person) and at-store pickup (especially during the pandemic).

In recent years, Walmart has made notable gains by expanding home delivery and pickup options for online orders. For instance, Walmart has grown its share of male customers and younger customers, as well as those with school-age children and those in the highest income brackets.

The gap between Amazon’s e-commerce sales and Walmart’s e-commerce sales remains significant

– in the hundreds of billions of dollars each year. But so, too, is the opportunity.

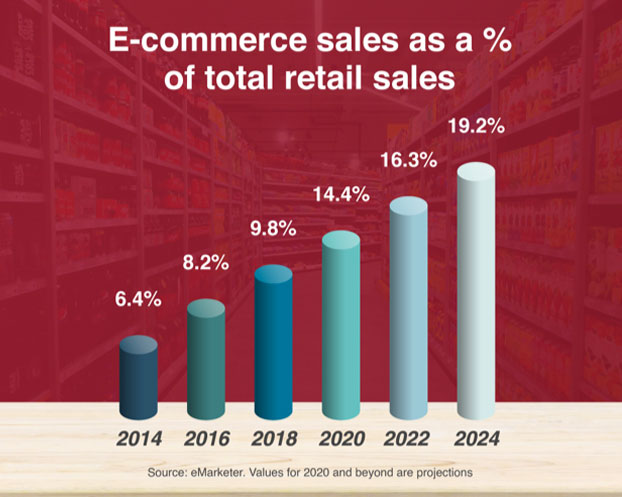

E-commerce represented just 6.4 percent of total retail sales in 2014, but eMarketer

predicts it will likely exceed 14 percent this year and grow to nearly 20 percent

by 2024.

The gap between Amazon’s e-commerce sales and Walmart’s e-commerce sales remains significant

– in the hundreds of billions of dollars each year. But so, too, is the opportunity.

E-commerce represented just 6.4 percent of total retail sales in 2014, but eMarketer

predicts it will likely exceed 14 percent this year and grow to nearly 20 percent

by 2024.

When I bought my toothpaste, the two retailers were virtually equal in every area. At that moment, however, Amazon’s online convenience won out over Walmart’s in-store convenience simply because I didn’t want to put on a mask and mingle with other shoppers just to buy one item.

One area where both retailers seem to over-invest is in speed of delivery. What’s more important, according to research, is reliability of delivery – having items in stock and delivering them when promised.

Amazon, for instance, dealt with backlash from its customers in the early months of the pandemic because of inability to make good on two-day delivery promises. It would be better for a retailer to offer a four-day delivery and deliver in four days (or sooner) than to promise two-day delivery and get it there in four days (or later).

Walmart shoppers also found that many popular items were not in stock in their local stores during those early months of the pandemic. Worse, some items showed up as in stock when ordered for pick-up or delivery but were out of stock when the order was filled. The customers didn’t have to pay for the unavailable items, but they felt the frustration of not getting what they wanted when they needed it.

The Influence of Technology On Retail

In 1965, Intel co-founder Gordon Moore wrote a paper for Electronic Magazine in which he suggested that the number of transistors incorporated into an integrated circuit chip would double every year. Later, he revised it to every 24 months, and the prediction has proved so accurate that it’s been labeled as “Moore’s Law.”

This concept has guided long-term planning in the semiconductor industry for decades, and the idea has been refined to include a correlation to price: we can expect the speed and capabilities of computers to double every two years while the price of the technology is cut in half. Customers have come to expect this rapid change in features and pricing, which is why computers, smartphones, and other gadgets typically introduce new or improved models every two years or less.

The Omnichannel Retail Law

Retail is evolving into a similar model, which I would like to call the Omnichannel Retail Law: With increased competition, customer expectations, and advancements in technology, retailers now have to double the number of new features they offer to customers every 18-24 months to maintain the same margins they are getting today.

Customers are more demanding and more in control than ever, which means retailers are looking for every opportunity they can find to create an edge, however brief, in an environment of increasingly thin margins. As a result, omnichannel retailing is in many ways mirroring the features-based approach of the technology industry.

This is evident in several areas, but many of them are driven by push-to-win customers with a shopping experience that has less friction and more convenience and value.

This accounts for improvements to apps and websites, which allowed me to make the snap decision to buy my toothpaste online rather than in a store. But it’s not just about improving online shopping. It also is driving the development of services like scan-and-go shopping in stores through the mobile app, cashier-less stores, zero-inventory stories, and advancements in delivery methods like drones. It also accounts for behind-the-scenes technology improvements that address efficiencies around things such as inventory management.

And it’s not just technology that’s evolving. Concierge services and appointment-only shopping – once found only in retailers selling luxury items – are making their way into all levels of the market. Best Buy, for instance, responded to COVID-19 in part by launching a program in April that allowed shoppers to reserve 30-minute slots that paired them with an employee during their visit. Furthermore, Walmart recently announced that it will pilot technology service centers in some of its stores as a potential alternative to Best Buy’s Geek Squad and Apple’s Genius Bar.

The Central Focus of Retail

The consumer, as the founders of Walmart and Amazon have both said in their own ways, has always been the central focus in retail.

Sam Walton listed “exceed your customers’ expectations” as one of his 10 Rules for Building a Business, and often said, “There is only one boss; the customer. And he can fire everybody in the company from the chairman on down, simply by spending his money somewhere else.”

Jeff Bezos, meanwhile, has attributed Amazon’s success to living out three big ideas: “Put the customer first. Invent. And be patient.”

Those tenets continue to ring true in the hypercompetitive omnichannel world, but so, too are the challenges that come with living them out.

Like many other consumers, I have grown accustomed to multiple options, and a number of factors come into play when I consider when, where, and how to make a purchase. There are times when I want to go into a store, times when I want to order online and pick up my purchase, and times when I want to have it shipped to my home – even if I ordered it from the parking lot of a competitor’s store.

The more options a retailer provides, the more likely it will have the right one in the right moment to generate a purchase. The challenge for traditional retailers is to reimagine their in-store retailing experiences to keep physical stores viable and profitable while also growing their e-commerce share. Amazon (and other traditional online sellers) have the opposite challenge – they must figure out ways to maintain or grow their online advantage while developing in-store options.

Only time will tell if the Omnichannel Retail Law will hold into the next few decades, but this much is certain: Technology is a great enabler and the line between physical and online retail will continue to fade (but not vanish) for many, many years to come. The brands that best use technology to serve their customers’ needs are the brands that will thrive.