Kroll’s South Loop in Chicago once offered a Captain Crunch French Toast, a favorite among football fans looking for breakfast when the hometown Bears had a game at nearby Soldier Field. Or fans might have stopped by later in the day for a burger, one (or more) of the 99 beer options, and a game of shuffleboard.

The eatery’s location on Michigan Avenue, less than a mile from the football stadium, made it a convenient gameday stop. But in September 2020, Kroll’s closed because of the pandemic. It reopened in May 2023, but for less than two years before shutting down for good after 17 years of operation.

Professional sports teams are rightly seen as an economic benefit to their communities, and businesses that operate near arenas and stadiums are particularly dependent on the fans who attend events at the venues. Many businesses hung on through the pandemic and others, such as Kroll’s, were left to ponder what might have been if they could have generated more consistent revenue during the crisis.

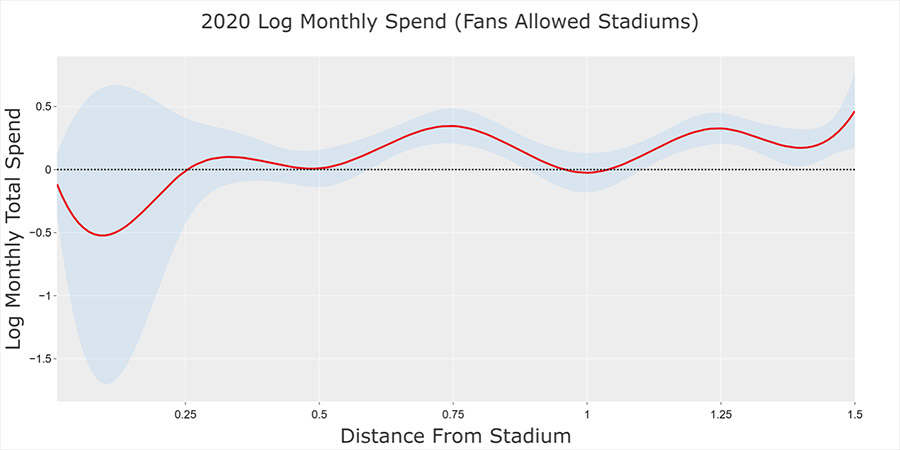

In fact, research by University of Arkansas graduate student James Wallis found that businesses operating within 1.5 miles of NFL stadiums generated $10 million a month in revenue if fans were allowed at games during the pandemic. And research by MIT, Wallis points out, found that the counties where those stadiums are located showed no increase in COVID-19 infections over counties with NFL teams that didn’t allow fans. Thus, the businesses in areas where fans weren’t allowed—including Chicago—suffered “a huge financial loss,” Wallis said.

The research by Wallis was part of a capstone project for his Economic Analytics II class in the 10-month Master of Science in Economic Analytics program at the Sam M. Walton College of Business. By looking at credit and debit card transaction data from 2020 and 2021 for businesses around 58 stadiums that host NFL and NBA games, Wallis was able to analyze the financial value those stadiums bring to cities and the “value at risk” during disastrous events such as the pandemic.

During the pandemic, of course, businesses in the retail, food service, and entertainment and leisure industries saw huge dips in revenue. But there was a significant decrease in spending at these types of businesses if they were located within 1.5 miles of the stadiums compared to those further away, Wallis said.

“I thought maybe there would be a decrease around the stadium,” he said. “Sometimes stadiums are out of the way from other things, and especially during COVID people weren't going out. So I assumed there’d be some financial loss around the stadiums.”

It also made sense that the 16 teams that allowed fans for NFL games during the pandemic would provide some economic relief to their area businesses. But $10 million in revenue per month was a higher number than Wallis expected.

“My hope is that findings like these can help guide policymakers and or team owners to make more informed decisions if another, similar situation were to arise,” Wallis said.

Wallis took on the assignment after one of his professors, program advisor Hyunseok Jung, showed him the type of data that was available on the topic. As a sports fan, Wallis found the data interesting, but he also sees this type of research as instrumental in understanding the economic value of sports teams on their communities and the impact of policy decisions on the economy during a crisis. With more analysis, for instance, he said a researcher might better pinpoint “the threshold around stadiums where businesses are going to take a big jump in revenues” because of their proximity to a stadium or arena.

Wallis said he would enjoy taking what he learned from the class and the program into a job with a professional sports team, but his bigger interest has to do with behavioral economics, which is something he could apply in healthcare or many other industries.

“Behavioral economics is kind of the mix of economics and psychology,” he said. “That’s what I’ve studied the most and what I’m most interested in. We have a brilliant behavioral economist in the Walton College of Business, Puja Bhattacharya. I took her classes as an undergraduate and as an elective in this graduate program.”

Wallis brought a different perspective to the program than some of his classmates because he spent a few years working in the oil and gas industry in Colorado after graduating from high school in Longview, Texas. He saved money and began his college journey when he was 22, paying his own way for two years at a small Texas University and then transferring to the UA to complete his degree in economics.

After discussions with economics Professor Robert Stapp (his mentor) and department chair Raja Kali, Wallis saw the data analytics program as an opportunity to sharpen his technology skills. Now at 27, he is finishing his graduate degree and ready to return to the workforce.

“This program gave me confidence in my ability to understand the process of analyzing economic data,” he said. “If I was in a job or if someone said, ‘Here’s some raw data that you could download.’ I would know how to clean it, get it ready for analysis, analyze it, interpret the results, visualize the results, and pull whatever value there might be from it. I feel like I could do that whole process. It gives you a general understanding and it gives you a knowledge of what the tools are, what the tools are used for, and how to get access to information or get access to the tools you need.”

The hands-on involvement of faculty at the Walton College helped stoke the fires of his interests in economics and gain a better understanding of how to spot potential flaws in analysis that might result in inaccurate or invalid conclusions.

“Dr. Jung was really good about helping us keep the integrity of the process so we’re not going to make some bold claim that’s not true,” he said. “We’re going to go through it the right way. He really was instrumental in walking us through the whole process, but also giving us enough autonomy and letting us fly a little bit and go on our own.”

Originally from Longview, Texas, James Wallis received his undergraduate degree in

business economics from the University of Arkansas. He is currently a final-year master's

student studying economic analytics at the Sam M. Walton College of Business set to

graduate this month. He plans to pursue an industry career in data science or economics

before potentially returning to school for a Ph.D. in behavioral economics.

Originally from Longview, Texas, James Wallis received his undergraduate degree in

business economics from the University of Arkansas. He is currently a final-year master's

student studying economic analytics at the Sam M. Walton College of Business set to

graduate this month. He plans to pursue an industry career in data science or economics

before potentially returning to school for a Ph.D. in behavioral economics.