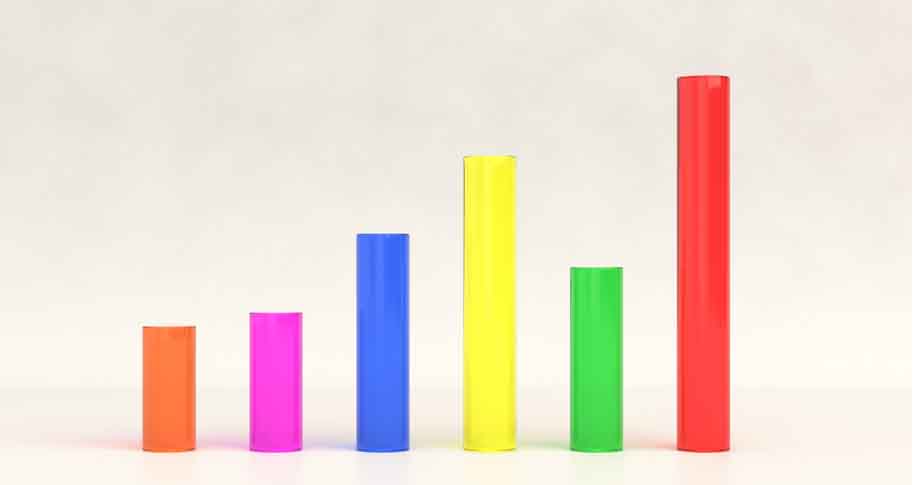

Bar graphs are not made equal. Javad Mousavi, assistant professor of marketing at the University of Arkansas, points out that rating bar graphs come in two varieties: proportional and simple. A proportional bar graph, like Amazon’s, has two fixed points, 0% and 100%, so the magnitude of any given review type is displayed as a proportion of 100%. A simple bar graph, such as Google’s, is only fixed at 0. The bars are instead limited by the peak value. So, if most reviews are 5-stars, then the 5-star bar will look like 100%, and the other bars will adjust to suit this limit.

There has been extensive research on how the content of verbal reviews changes consumers’ perception of and intention to buy a product. There is, however, little research on how the visual display of reviews in aggregate changes consumer intentions, even though the impact of visual stimuli is well documented.

In his recently published article, “Unveiling Stars: How Graphical Displays of Online Consumer Ratings Affect Consumer Perception and Judgement,” Mousavi and his coauthors, Surendra Singh(University of Kansas), Promothesh Chatterjee (University of Utah), and Tamara Masters(University of Utah), investigate how this subtle difference in display changes how consumers interpret the relative positivity of reviews.

Their study suggests that customers are more likely to have a positive impression of a product when its reviews are displayed in a simple bar graph rather than a proportional one. Of course, the degree to which bar graphs impact customers’ views is affected by the peak value displayed on the bar graph and the relative difference between positive and negative reviews.

It’s not enough to just have a positive rating. Most ratings skew high with an average of around 3.8 stars in most industries. And 87% of consumers will not even consider a product with fewer than 3 stars. Not only will it change the likelihood of a customer choosing your product over another, the display of ratings can also impact future customer ratings.

Formatting and Online Word of Mouth

A product’s ranking is one form of online word of mouth, which is simply when customers learn about a product and make decisions on whether to purchase the product from other customers. If it’s good, you’d be hard pressed to find better and cheaper marketing. If it’s bad… well, good luck.

And while there has been a lot of work on various aspects of online word of mouth, this research asks how the graphical display of word of mouth changes consumers’ impressions. This is important for online businesses because their customers rely on rating distributions, and other research has found these distributions are the most used form of online word of mouth. And, as the researchers say, the cost of changing these displays is negligible, so companies can quickly adapt to the best format for their products.

The primary difference between these two types of bar graphs is how easy it is to make part-to-whole comparisons. On a proportional bar graph, the axis of which maxes out at 100%, you can easily tell the proportion of 5-star reviews to all other reviews. If 36% of the ratings are 5-star, it is obvious to the viewer that 64% are lower than 5-stars.

A simple bar graph, on the other hand, has no fixed terminus on its x-axis. It merely ends at the peak value (the rating that has numerically the most votes), and they usually display the number of ratings per rank. For this reason, the x-axis is almost always less than 100%, but a consumer can quickly extract information such as the most common rating and the raw number of ratings at each level.

The Power of Simplicity

In a series of six online studies, Mousavi, Singh, Chatterjee, and Masters systematically analyzed the effect of how the graphical display of ratings changed consumers’ impressions of a product. Five of the studies had participants answer questions about products given a particular display of ratings, and the final study tested the initial results against restaurant ratings on Google and TripAdvisor.

The researchers found that “simple bar graphs led to higher product evaluations,” and the greater the difference between the number of high and low ratings, the stronger this relationship was. In the first study, participants considered the ratings of both a stapler (or a less significant purchase) and a laptop (or a more significant purchase); and while participants did rate the laptops less positively, the researchers found the product type did not change the effect of the bar graph on participants’ evaluations. This essentially means the simple bar graph has the same net increase in positive perception regardless of what product is being considered.

In the second study, the researchers had participants estimate the number of 5-star ratings based on unlabeled bar graphs. In every case, participants overestimated the number of 5-star ratings when asked to base their guess on a simple bar graph! The researchers explained that “participants in the simple bar graph condition recalled significantly greater values than those in the proportional graph condition.” Furthermore, Mousavi, Singh, Chatterjee, and Masters argue that simple bar graphs “distort consumers’ mental representation of the ratings.”

When looking for alternative explanations of the effect, the researchers had some participants answer similar questionnaires but with variations on the graphs. In these cases, they showed proportional graphs with high contrast color variations and displayed simple graphs with percentages. The results of this study showed that even with other visual data to reference, the effect of the simple bar graph on raising consumer impressions remained consistent.

Impact of Online Reviews on Real Restaurants

The final study the researchers conducted was based on a collection of 343 New York restaurants found on both Google and TripAdvisor. As noted above, Google displays its ratings with a simple bar graph, and TripAdvisor uses a proportional bar graph.

With this data, Mousavi, Singh, Chatterjee, and Masters found that business received higher ratings on Google than on TripAdvisor. Paired with data from the researchers’ other studies, these findings suggest that simple bar graphs actually influence the way consumers rate a product after they’ve purchased it. Consumers both think of the product more positively and then rate it more highly too.

In this specific case, a simulation suggested that TripAdvisor users would rate restaurants on that platform 6.59 out of 10, whereas Google users would rate the same restaurants as 7.44 out of 10. That’s 13% higher! And apparently largely due to the display of those ratings.

The researchers are careful to point out that this study does not analyze the demographic differences between TripAdvisor and Google users. They also note that there are significant differences in how businesses monitor their Google reviews compared to their TripAdvisor reviews, so they cannot attribute all of the difference to the graphical display. But it is enough to show their results hold outside of the laboratory.

Managing Your Online Word of Mouth Marketing

You can’t control what your customers say about your product, but you can change the way they perceive online word-of-mouth reviews. And it appears simply changing a bar graph’s terminus from 100% to the peak value is enough to prompt consumers view your products and services more positively. Also, the cost of altering the display of online reviews is negligible compared to other kinds of online marketing campaigns.

The researchers suggest that “businesses would benefit from promoting their products or services on platforms that use simple bar graphs” and that they “can improve their products’ future ratings by using simple bar graphs on their websites.” Online word-of-mouth marketing can be a game of inches, so even small improvements can have large financial impacts on businesses.

Mousavi is aware of the possibility that businesses could use this data unethically and does not advocate every kind of product ought to get this treatment. For example, he points out that the risk to patients of overestimating the benefit of prescription drugs outweighs any benefit a company might receive from changing the graphical display of reviews on websites like AskAPatient.com. We could likely add financial services and insurance to the list of these products, really anything where customers specifically benefit from having as objective a view of the service or product as possible.

From a consumer’s perspective, it’s interesting to see how our perceptions are swayed by subtle changes to the display of ratings and other aggregated data about a product. Mousavi’s research shows that this relationship is stronger when there is a smaller difference between the peak value and other ratings, so a flood of 5-star reviews can minimize the visual impact of dispersed lower ratings on a simple bar graph, even if there are more lower ratings than the 5-star reviews.

Mousavi and his coauthors hope this work will inspire future research, such as whether color and the orientation (horizontal vs. vertical) of a bar graph changes consumers’ views of a product. They say that the aspect ratio of bar graphs could also offer interesting insights for digital marketing. Savvy marketing can have simple and inexpensive solutions, and savvy consumers have another thing to consider online.