As a graduate student, my laptop contains and is my entire life; not a day goes by without using it. With exams and papers always around the corner, I make a great effort to prepare by utilizing online textbook systems for easy access and editing features. However, I am often met with extended loading times, error pages, or no content at all. In other words, system delays.

When these interruptions occur, I try reloading the website or system – doing anything I can, really – to continue studying. Through no fault of my own, some delays are relentless, and I find myself abandoning the system altogether. Because I am switching to another task or becoming distracted, my performance drastically plummets, and I lose valuable time and resources on a fruitless effort.

If this is a common – and aggravating – occurrence, you are not alone. System delays, particularly long ones, cause brain state switching, which is when the brain changes from engaged to unengaged. More specifically, when long system delays occur, the brain switches from its current task state into a different state, and then the brain must switch back before continuing the task.

Despite advancements in technology that enable proactive improvements in IT infrastructure and network speeds, system delays stubbornly remain a noteworthy issue among individuals who utilize the Internet and technology. In short, almost everyone!

System delays have negative effects on user experience, information search tasks, job satisfaction, business revenue, and learning complex material. However, research has yet to uncover why the consequences are so detrimental to user performance and brain state switching.

This gap in the research led Kevin Harmon (University of Arkansas), Hansol Lee, Bahar Javadi Khasraghi, Harshit S. Parmar, and Eric Walden to examine how long system delays impact brain state and how interventions can overcome this phenomenon in their recent article, "Delays in Information Presentation Lead to Brain State Switching, which Degrades User Performance, and There May Not Be Much We Can Do About It."

Persistence of the Problem

Nowadays, workplace IT problems are so frustratingly persistent that Americans are quitting their jobs; or, at least, searching for new ones. Out of 1,000 surveyed hybrid and remote workers and 1,000 IT professionals in 2022, 11% left their job for better technology and 42% applied to other jobs with the same intention. Additionally, 20% claim to “always” have bad experiences with workplace technology, while 35% rank system delays as the top workplace grievance. The respondents report losing an average of 102 minutes (about 1 hour 42 minutes) of productivity a week due to about 18 disruptions, including: slow websites, a lack of access to certain online resources when working from home, restarting the computer, connecting when switching from the office to at-home working, and troubleshooting by themselves.

According to Harmon, fully loading a desktop webpage takes on average 10.3 seconds and 15 to 27.3 seconds on mobile devices: “The persistence of the problem of delays indicates the importance of continuing to gain a better understanding of how delays impact users.”

With improvements to system efficiency, users would experience a reduction of brain state switching. More importantly, they would also experience increases in satisfaction, retention, commitment, engagement, and performance. To understand how long system delays harm users due to brain state switching, the research looks at three constructs: delays, brain state switching, and performance.

System delays are always present, yet the difference between long (eight seconds or more) and short delays (two seconds or less) matters. During long delays, brain state switching is more likely: the non-attentive brain regions become more active, and decision-making performance in the following task reduces. The extent of the effects that system delays have on users is much more impactful when we understand how brain state switching occurs.

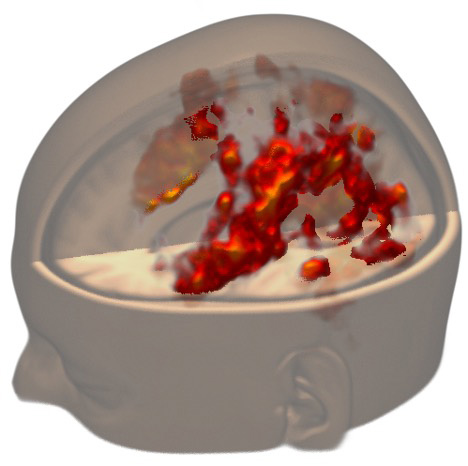

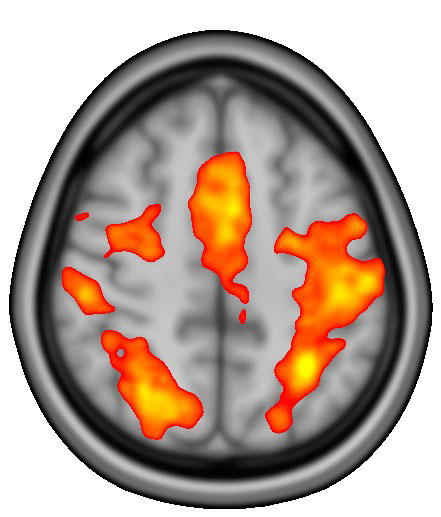

Brain state is a pattern of activations – an overall increase in local blood oxygenation – between brain regions that correspond to behavioral tasks, which is detected using fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging). Therefore, when brain state switching occurs due to a switch in behavioral task, the pattern changes, as well. Brain state switching further harms the concept of individual performance especially in correlation with system delays.

Performance is the number of seconds it takes a person to make a decision after a presentation of information that is useful to that decision. When information systems do not interrupt the brain state with long delays, it enables individuals to make efficient decisions and performance is greatly improved.

In all, when a delay is short and the system presents task-relevant information, the user is in a task-appropriate brain state, enabling greater task performance. Contrastingly, when the delay is long, the user switches from a task-appropriate state to another, experiencing, perhaps, a state of distraction and unproductivity.

Delaying Neurology and Behavior

Despite the prevalence of system delays, we have little knowledge —beyond that of annoyance— of how these delays harm user performance. Additionally, while there are proven interventions for user perception of delayed wait time, none work to reduce the impact of delays on users. In fact, Harmon says that “most research on system delays focuses on user attitudes toward delays or systems with delays rather than how and why performance can be harmed.” To assess the possibility of interventions that limit the effect of system delays on performance, researchers must understand why they occur in the first place.

Addressing the first gap through neuro information systems (NeuroIS), the researchers propose that an idle brain does not remain idle for long. When brain state switching takes place, it degrades task performance, is costly to brain metabolism, and, thus, can lead to fatigue and ego depletion.

Harmon’s experiments demonstrate that when system delays cause brain state switching, the individual’s performance is affected on many levels. In addition to the previously known impact of long delays on user experience, information retention, job satisfaction, business revenue, and learning ability of complex material, researchers can now include neurological and behavioral effects to the list.

Using fMRI, Harmon makes several findings. When long delays occur, so does brain state switching, making the performance of tasks slower and more metabolically costly. Still, Harmon wonders about brain states in comparison to what is considered a “task,” leaving room for future research to expand on this gap.

Elimination vs. Mitigation

The researchers, in questioning how delays affect user performance through brain state switching, find that the number of decisions a person makes reduces by 10% after a long system delay. In terms of the people that system delays and brain state switching affect, the researchers propose steps for businesses to improve response time and limit delays. Creating separate mobile pages or apps with less content to load is a worthy investment to reduce delays. Web designers can minimize graphics per page to decrease loading times. Additionally, if cloud and mobile computing and large software create long delays, businesses should consider implementing software interventions that fill delays, such as a countdown timer.

These mitigative steps are, however, limiting to businesses and individuals. While they can mitigate the negative impacts of long delays on user performance, they do not eliminate them. “It is possible,” Harmon says, “that brain state switching is a biological process that cannot be completely avoided through interventions.”

So, as long as we continue using technology and the Internet, system delays are inevitable, and, therefore, so is the negative impact on our experience and performance as users. Hopefully, more research on this issue occurs, we may eliminate system delays, negative impacts, and brain state switching. If we find ourselves so fortunate, it is safe to assume that individual decision-making processes and system experiences will be unprecedented without the pesky interference of long system delays.

Alyssa Riley is a second-year graduate student earning her master’s degree in News

Narrative Journalism. Attending the University of Arkansas as an undergraduate student,

she earned her bachelor’s degree in News Editorial Journalism while working in numerous

writing, editing and social media roles. In addition to writing for Walton Insights,

she has begun a sports media internship with Hogs Plus Content Network and freelances

for Celebrate! Arkansas Magazine. After earning her master's, Alyssa hopes to work

in the magazine industry, specifically covering arts and culture, entertainment and

lifestyle genres.

Alyssa Riley is a second-year graduate student earning her master’s degree in News

Narrative Journalism. Attending the University of Arkansas as an undergraduate student,

she earned her bachelor’s degree in News Editorial Journalism while working in numerous

writing, editing and social media roles. In addition to writing for Walton Insights,

she has begun a sports media internship with Hogs Plus Content Network and freelances

for Celebrate! Arkansas Magazine. After earning her master's, Alyssa hopes to work

in the magazine industry, specifically covering arts and culture, entertainment and

lifestyle genres. Dr. Kevin A. Harmon is an Assistant Professor in the Information Systems Department,

specializing in the impact of system delays on user performance and user experience

(UX) across diverse contexts. His current research focuses on elucidating how latency

influences user interactions with technology, shedding light on critical aspects of

system design and its implications for efficiency and satisfaction. Dr. Harmon adeptly

applies his extensive background in psychology to enrich his analysis, offering a

broader understanding of the human-technology interface.

Dr. Kevin A. Harmon is an Assistant Professor in the Information Systems Department,

specializing in the impact of system delays on user performance and user experience

(UX) across diverse contexts. His current research focuses on elucidating how latency

influences user interactions with technology, shedding light on critical aspects of

system design and its implications for efficiency and satisfaction. Dr. Harmon adeptly

applies his extensive background in psychology to enrich his analysis, offering a

broader understanding of the human-technology interface.