Supply Chain Stress Testing: To Mandate, or Not to Mandate?

June 18, 2021 | By Ron Gordon, Andrew Balthrop, Donnie Williams, Brent Williams and Brian Fugate

From the Supply Chain Management Research Center at the University of Arkansas

On March 17, 2000, lightning struck an Albuquerque, New Mexico, powerline. The resulting surge overloaded the power grid and started a fire in a nearby factory. The blaze destroyed millions of microchips.

Unfortunately for Swedish cell phone company Ericsson, that plant was their only microchip supplier. Months of lost production and $400 million in lost sales taught the firm a costly lesson in supply chain risk.

In 2000, supply chain “stress testing” was a thought exercise. Managers gathered around a table and discussed various “what ifs” involving things like unexpected demand spikes or the temporary loss of a supplier and how to mitigate those risks. Arguably, if Ericsson’s managers conducted such an exercise, it should have been sufficient to help them realize the precariousness of their position and take action. After all, fellow plant customer Nokia identified the risk well before the fire, implemented a multiple-supplier strategy, and barely missed a beat while the Albuquerque factory was down.

Like cell phones and the microchips inside them, supply chain stress testing has evolved considerably since 2000. Today, many companies use stress testing models that identify vulnerabilities and offer suggestions for addressing them, such as diversifying the firm’s supplier base.

The pandemic’s well-publicized shortages have led some practitioners, researchers, and politicians to champion stress testing as a way to make supply chains more resilient during future disruptions. After campaigning on a promise to “institute an ongoing, comprehensive government-wide process to monitor supply chain vulnerabilities,” President Biden ordered a 100-day audit of supply chains for critical products, including pharmaceuticals, semiconductors, large-capacity batteries and minerals used in electronics. That audit just ended and officials are beginning a broader year-long audit that will examine other industries, including transportation and food production.

Pending the results of the second audit and the recommendations of a newly-established supply chain task force, officials are considering options such as incentivizing firms to re-shore manufacturing, encouraging companies to stockpile certain inventory, and requiring firms to stress test their supply chains to identify vulnerabilities. Well-intentioned regulatory interventions can produce unintended consequences that are not easily predicted, so it is encouraging that policymakers are conducting audits which may show that firms are already addressing supply chain vulnerabilities and policy changes are unnecessary.

Supply Chain Stress Testing

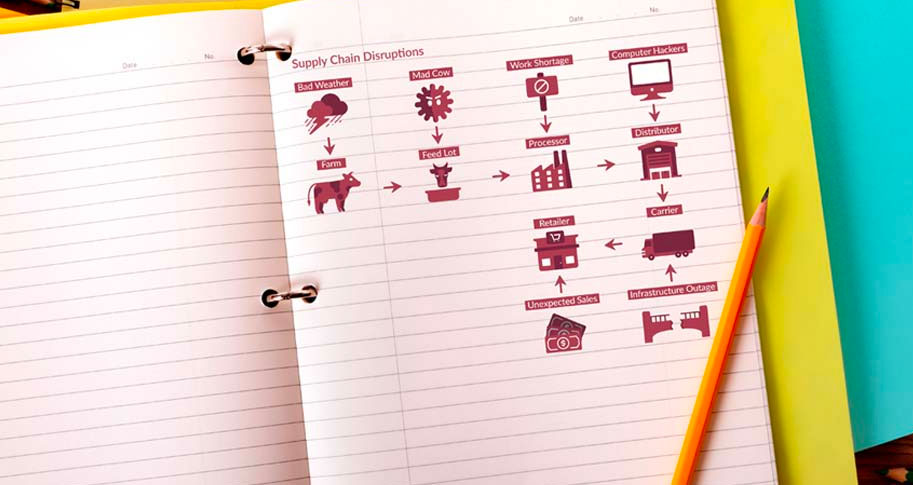

Traditional risk management models rely on historical data to assess the likelihood of common risks, such as poor supplier performance or forecasting errors, and suggest ways to manage those disruptions. Conversely, stress tests help firms prepare for catastrophic disruptions whose rarity and unpredictability makes historical data relatively useless for forecasting purposes: earthquakes, pandemics, factory fires, etc. Rather than quantifying the likelihood of a particular disaster, the tests are intended to help make supply chains more resilient and able to better withstand disruptions.

Computer-based modeling and simulation, a method championed by MIT’s David Simchi-Levi, can provide valuable insight. By analyzing data from various supply chain nodes, creating a digital twin/model of that supply chain, and subjecting the digital twin to scenarios involving disruptions to one or more nodes, stress tests can identify vulnerable points in the supply chain and suggest mitigation strategies. The tests can be tailored to various industries and identify risks at the product, category or supplier level.

A benefit of stress testing is its ability to expose hidden risks involving suppliers. For example, while it would be obvious for an auto manufacturer to assess risks involving suppliers of costlier, high profile parts like seats or instrument panels, they may overlook a specialized supplier of O-rings or valves. Those parts account for a tiny portion of the carmaker’s annual spending, but a sudden disruption in their supply could stop the assembly line just as significantly as a shortage of more expensive parts. Stress testing can highlight such easily overlooked dangers and prescribe measures that can save firms the financial strain and embarrassment that would come with losing out on valuable production time because of a ten-cent part.

While David Simchi-Levi’s model is perhaps best known and others take slightly different approaches, the general concepts and goal remain the same. For example, Kearney’s stress test analyzes a supply chain using various scenarios, then categorizes vulnerabilities across eight dimensions: geography, planning, suppliers, inbound transportation, manufacturing, outbound distribution, product portfolio and platform, and financial/working capital. It then suggests risk reduction strategies for the problematic dimensions, such as investing in increasing end-to-end supply chain visibility to address planning problems or mapping alternate routes for outbound logistics when necessary.

Though stress tests have many benefits, they also have limitations. For instance, while stress testing models rely on information, most companies don’t know the identities of all the firms in their supply chain, partly because suppliers often consider their suppliers’ identities a “trade secret.” The secrecy shrouding parts of many supply chains will limit stress testing’s effectiveness as long as that mystery remains. It is critical that managers view stress testing as part of a risk management strategy rather than a silver bullet that makes other methods unnecessary.

To Mandate?

Some proponents of supply chain stress testing argue that it should be required by law, particularly for “critical” supply chains. They often draw parallels to the banking stress tests federal policymakers instituted in 2010 after the Great Recession showed that many banks were overleveraged in ways that threatened to produce an even greater financial disaster if left unchecked. The stress tests assess banks’ financial health and ability to withstand hypothetical scenarios. For example, the Federal Reserve may require banks to demonstrate how well they could withstand a national economic downturn that includes high unemployment and a housing market crash.

While many believe these tests have improved the health of our financial system and some credit them for helping the economy perform relatively smoothly during the pandemic, others insist that the tests have had negative unintended consequences and question whether they are becoming mere compliance exercises as bankers learn their intricacies.

Banks and supply chains differ in many ways, one of which is that the federal government’s authority to regulate some supply chains is less certain. Federal agencies have varying degrees of power over the industries they oversee, so attempts to mandate stress testing could face legal challenges.

But whether they are considering mandating stress tests or merely requesting them, policymakers should cautiously consider the potential for their well-intentioned actions to produce negative unintended consequences.

For example, the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010, which mandated banking stress tests, also included a provision on “conflict metals” such as tin, tungsten, tantalum and gold. It required publicly traded companies whose products included metals purchased from areas where mining profits fueled warfare to audit their supply chains and reveal the precise source of those metals to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

The provision was intended to improve life in the Democratic Republic of Congo by reducing armed groups’ ability to profit from mines they control, but research suggests it further destabilized the DRC, at least in the short term. Instead of going through the trouble of auditing their supply chains, trying to separate “conflict mines” from legitimate operations, and risking having their brands damaged by being publicly shamed if they failed to correctly distinguish between the two, many companies pulled out of the DRC altogether. As mining for everything except gold slowed, many miners’ quality-of-life plummeted. Some firms – particularly non-Western firms who were not governed by Dodd-Frank – continued purchasing the metals, though at a steep discount thanks to the sudden buyer’s market. And conflict grew more desperate as armed groups tried to compensate for lost income by seizing new resources.

In 2017, researchers found that Dodd-Frank “increased the likelihood that armed groups looted civilians and committed violence against them.” A 2018 study finds that some DRC territories experienced 44% more battles, 51% more looting incidents, and 28% more episodes of violence against civilians after Dodd-Frank. Another researcher finds that “the Dodd-Frank Act doubled the prevalence of conflict in the DRC.”

Policymakers should consider the possibility that government pressure to stress test will lead many firms to pull out of developing countries in the name of risk mitigation, producing a destabilizing effect and lowering the quality-of-life in those areas. Similarly, some firms might view the testing as a panacea, creating a “moral hazard” where companies whose supply chains pass the government-endorsed stress test feel less compelled to work to identify risks that the testing overlooks or misidentifies. It is also possible that sufficient government pressure to stress test, including potential fines or the threat of public shaming, could lead firms to become overly cautious in their risk management approaches, damaging both supply chain efficiency and effectiveness.

If policymakers decide to steer companies toward stress testing, they should be mindful that supply chains differ considerably from industry to industry, so a one-size-fits-all approach would be ill-advised. Relatedly, requiring firms to use a specific test or telling them exactly how to stress test their supply chains would likely produce more severe unintended consequences than would a mandate that requires stress testing while allowing individual firms to decide how to conduct it.

Or Not to Mandate?

As government officials audit various supply chains, they will likely find that most major firms are already stress testing – though individual firms may call it something else – or plan to do so. After all, not having product available to sell is bad business. A recent Gartner survey of sourcing and procurement executives showed that 87% said they needed to invest in making their supply chains more resilient. A separate Gartner poll of functional leaders ranked supplier risk management as the number one area for improvement with 75% anticipating changes in their firm’s approach.

Market forces incentivize firms to learn from their mistakes and correct known problems before they cause further financial or reputational damage. For example, after the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake devastated Toyota’s operations and reduced production 78% over the following year, the firm overhauled its approach to risk management. Part of that overhaul involved improving communication with semiconductor suppliers, regularly reviewing semiconductor inventories, and designing vehicles with the flexibility to accept different sized chips if necessary.

The lessons Toyota learned from the 2011 disaster have helped it navigate the pandemic more effectively than most. In May 2021, as a global chip shortage wreaked havoc on the automotive industry and many others, Toyota’s CFO Kenta Kon informed shareholders that the shortage should have no major impact on Toyota’s productivity.

In much the same way the 2011 earthquake led Toyota to reassess its risk management in ways that allowed it to fare better during the next major disruption, it is likely that the pandemic has caused many firms to adopt stress testing so they can withstand future disruptions more easily.