‘Those People Bought Walmart Stock Early’: The Development of Northwest Arkansas’ Supply Chain Cluster, 1975-2010

April 16, 2021 | By Ron Gordon

From the Supply Chain Management Research Center at the University of Arkansas

"To these children, to be born in Arkansas is a misfortune and an injustice from which they will never recover and upon which they will look back with bitterness when plunged, in adult life, into competition with children born in other states…" – U.S. Government Report on “The Public School System of Arkansas,” 1922

"I keep hearing all these jokes on TV about how people in Arkansas are still barefoot hillbillies. Sure, there are plenty of people living up in the hills and mountains in Arkansas. Why not? The scenery is breathtaking from their million-dollar houses up in those hills. Those people bought Walmart stock early. They paid cash for those homes." - Marilyn Schwartz, New Times in the Old South, 1993

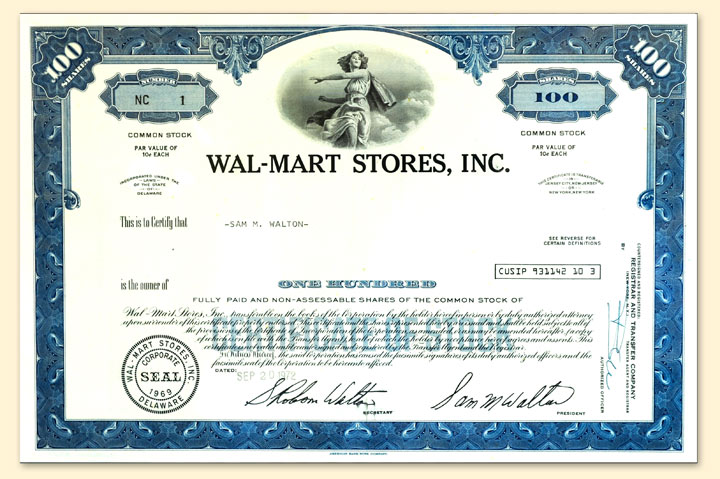

Long the target of exaggerated hillbilly jokes and accurate government reports, Arkansas began receiving a different kind of national attention in 1985, when Forbes magazine first ranked Sam Walton as the richest person in America.

The positive attention continued: the world’s largest poultry producer, a nationally successful transportation company, an American president, an NCAA men’s basketball national championship team. Sure, the hillbilly jokes continued, too. But they lost much of their sting, thanks to Arkansas’s newly bolstered reputation.

Many of the developments that boosted Arkansas’ national profile were inseparable from the growth of its northwestern corner’s supply chain cluster: a concentrated set of supply chain-related business activities. This article is the second in a three-part series examining the history of that supply chain cluster.

Innovation

By 1975, J.B. Hunt Transport Inc., Tyson Foods and Walmart were regional successes and few would have faulted Johnnie Bryan and Johnelle Hunt, Don Tyson or Sam Walton if they had chosen to rest on their laurels. Instead, they sought ways to improve and expand operations, elevating both their companies and their region to international fame.

When a reporter asked J.B. Hunt to reveal the secret of his success, he said, “I just haul the freight and the money rolls in.” Hunt’s reply belied the shrewd business decisions that made his and his wife’s trucking firm a Fortune 500 company. For instance, at a time when most trucking companies utilized owner-operators, the Hunts increased their profits by using company-owned equipment. Later, instead of following other trucking carriers by treating railroads as competitors, the Hunts partnered with the Santa Fe Railway and entered the intermodal business in 1989, using multiple modes of transportation to move freight in shipping containers. Today, J.B. Hunt’s intermodal segment generates most of its revenue.

Don Tyson made Tyson Foods a national brand partly by expanding beyond poultry into beef and pork in the late 1970s. Then, in the early ‘80s, the company began producing value-added offerings like chicken fingers and nuggets. The convenient products were a hit with parents, kids and institutions. This openness to innovation goes a long way in explaining why, in 1989, Tyson Foods was able to nearly double its market share by purchasing longtime rival Holly Farms, and not vice versa.

In his autobiography, Sam Walton wrote, “I’ve put up a pretty good fight every time somebody wants to buy some new system for this, that, or the other… but I eventually signed the checks.” Those checks covered the development of automated distribution centers in 1978, the use of barcodes at checkouts in 1983, and the installation of America’s largest private satellite system in 1987. These innovations helped Walmart create inventory and distribution systems that were, according to Walton, “the envy certainly of everyone in our industry, and in a lot of others as well.” Those systems, along with ‘80s creations like Sam’s Club and the first Supercenter, helped transform Walmart from a regional success to an international force. In 1970, the company’s 32 stores generated $8 million in profits (real 2020 USD). In 1990, its 1,528 stores earned $2 billion in profits (real 2020 USD).

Government Policy

Northwest Arkansas companies continued to benefit from certain state and federal government policies. For example, J.B. Hunt’s rise to national prominence was aided by the Motor Carrier Act of 1980, which deregulated trucking. Heeding the advice of a Chicago lawyer who insisted that deregulation was imminent, the Hunts expanded their fleet of company-owned trucks in the late ‘70s. After the federal government began allowing free market competition in previously restricted freight lanes, the Hunts’ firm experienced explosive growth. J.B. Hunt Transport Services, Inc. went public in 1983, at which time it was the eightieth-largest trucking firm in the United States. By 1987, it was the nation’s largest publicly-traded trucking company. In the decade following deregulation, the firm grew 2,000 percent.

By 1990, Northwest Arkansas entrepreneurs were also able to shape government policy. That year, Don Tyson hosted a barbecue at his Beaver Lake home. There, Sam Walton questioned members of the U.S. House Public Works and Transportation Committee about the discrepancy between Walmart’s high annual tax bills and the dearth of federal improvements in its home region. Three weeks later, the U.S. Secretary of Transportation came to assess the need for a new airport. Northwest Arkansas National Airport opened in 1998. Like Interstate 540 (now I-49), which was completed in 1999, the airport made travel to and from Northwest Arkansas much easier.

Sam Walton, Don Tyson, J.B. Hunt and others formed the Northwest Arkansas Council in 1990. The nonprofit organization helped push for the airport and continues working to secure government support and private funding to advance the region’s job opportunities, infrastructure, and quality of life.

Growth

The presence of three massive companies’ headquarters in Northwest Arkansas brought hundreds of firms to the region. Many were drawn by the desire to effectively work with world’s largest retailer, whose success was built on cutting out middlemen and negotiating directly with suppliers.

"There’s a difference between being tough and being obnoxious. But every buyer has to be tough. That’s the job… We would tell the vendors, 'Don’t leave in any room for a kickback because we don’t do that here. And we don’t want your advertising program or your delivery program. Our truck will pick it up at your warehouse. Now, what is your best price?' And if they told me it’s a dollar, I would say, 'Fine, I’ll consider it, but I’m going to go to your competitor, and if he says ninety cents, he’s going to get the business. So make sure a dollar is your best price.' If that’s being hard-nosed, then we ought to be as hard-nosed as we can be... If you buy that thing for $1.25, you’ve just bought somebody else’s inefficiency." - Claude Harris, Walmart’s first buyer

Walmart did not require its suppliers to establish offices in Northwest Arkansas, but many did so. Since 2000, over 300 Fortune 500 companies have established satellite offices in Northwest Arkansas, including Clorox, Coca-Cola, Colgate-Palmolive, Procter & Gamble, General Mills, Kellogg’s, Kraft Heinz, Nestlé and Unilever.

The arrival of so many businesses aided the development of two of today’s top logistics firms. Fort Smith-based ArcBest – parent company of ABF Freight – experienced some of its greatest growth since its 1923 founding during the period covered in this article, going public and purchasing two former competitors. In 2000, J.B. Hunt Transport Services and five others founded Transplace, a third-party logistics company offering services and technology to help firms manage transportation and improve supply chain performance. The Frisco, Texas-based firm grew rapidly, thanks largely to its Northwest Arkansas operations.

The influx of business fueled Northwest Arkansas’s economic and demographic growth. Between 2000 and 2010, its population increased 26.7%, to 424,404. By 2015, it was the only metropolitan statistical area in the state whose per capita income exceeded the national average.

Education

As the region grew, so did the University of Arkansas. Enrollment rose 28% between 2000 and 2010, reaching 21,406.

"Education… is the single area which causes me the most worry about our country’s future. As a nation, we have already learned that we must compete worldwide with everybody else, and our educational process has more to do with our ability to compete successfully than anything else. Unless we get ourselves on the right track pretty quickly, and start rebuilding our system into one that compares favorably with the rest of the world’s, we could seriously jeopardize the future of this great country of ours." – Sam Walton

The generosity of local entrepreneurs and businesses allowed the university to better serve its students and industry partners. The Walton family followed its historic 1998 gift of $50 million ($79.4 million in 2020 dollars) to what is now the Sam M. Walton College of Business with a $300 million ($431.6 million in 2020 dollars) gift to the university in 2002. Countless others made generous contributions of varying sizes, fueling the university’s rapid development.

The growing university continued its long-standing relationship with local industry, providing talented faculty to help solve real-world problems and capable graduates to fill openings. While the university lacked a department of supply chain management, by the mid-90s, professors such as John Ozment and Matt Waller were helping assure that the Department of Marketing and Logistics’ logistics and transportation students were among the nation’s best. The logistics and transportation major became one of the fastest growing in Walton College, leading administrators to hire more faculty and add new courses to try to meet the demands of both students and local firms.

Thanks to the largesse of local entrepreneurs and the expertise of its faculty, Walton College was home to several nationally competitive departments by 2010. Nonetheless, it was becoming apparent that the growth limiting factor for the budding supply chain cluster would be the number of skilled workers. Expanding this talent pool was a key challenge for the university, and for the businesses and cities in Northwest Arkansas. How these actors came together to overcome this challenge will be the focus of the final article in the series.