The Federal Reserve’s recent rate hikes should help curb inflation by reducing consumer spending.

Perhaps just as importantly, the rate hikes should show Americans that the bank is serious about taming inflation sooner rather than later. Public expectations about inflation’s trajectory help determine whether or not prices continue rising. Recent history shows what can happen when people believe inflation will keep getting worse.

The Great Inflation, 1965-1982

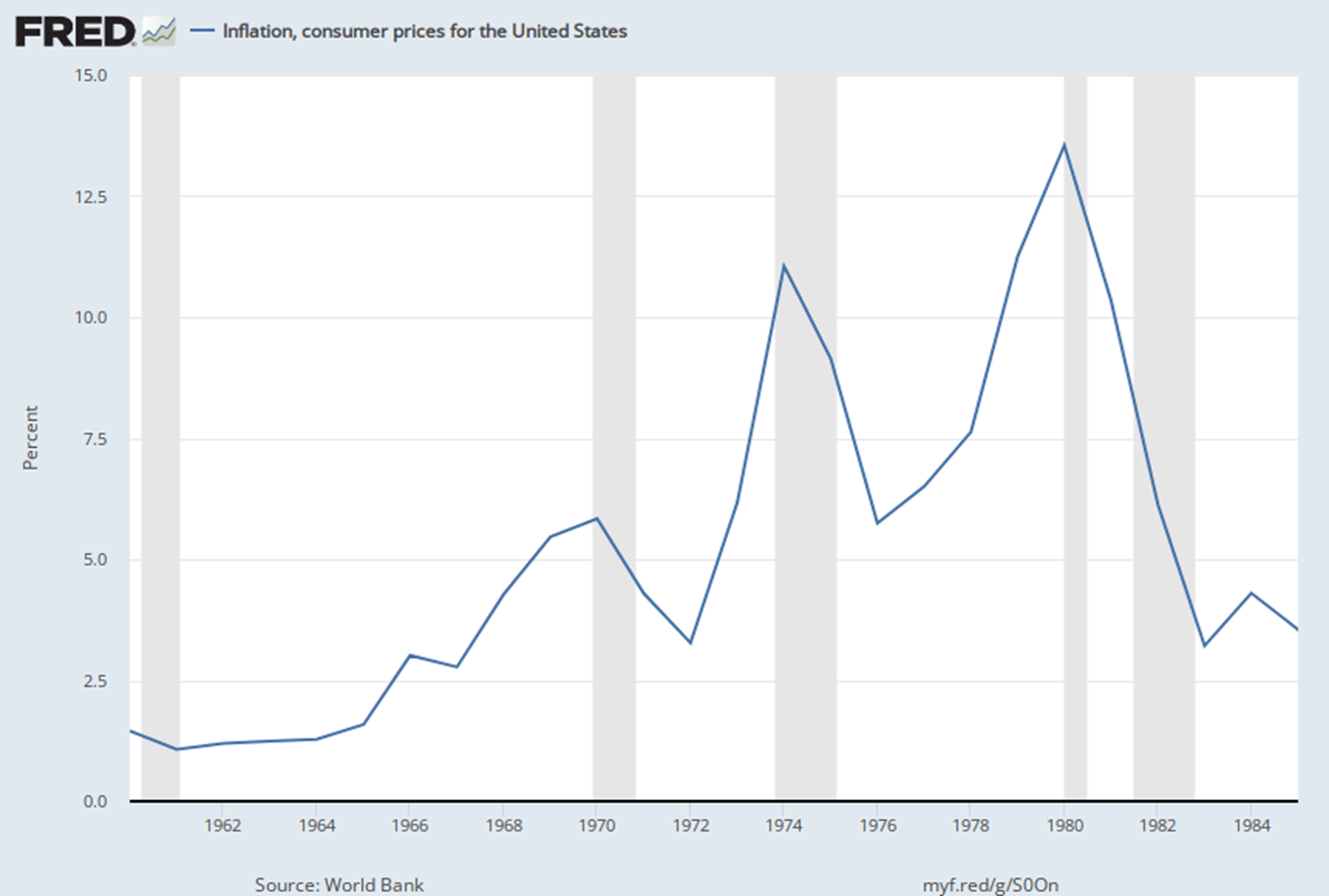

Inflation hovered around 1.2% throughout the early 1960s. The jump to 1.6% in 1965 marked the start of the Great Inflation, which peaked at 13.5% in 1980. During that time, policymakers gave Americans little reason to believe that the federal government was willing or able to effectively fight inflation.

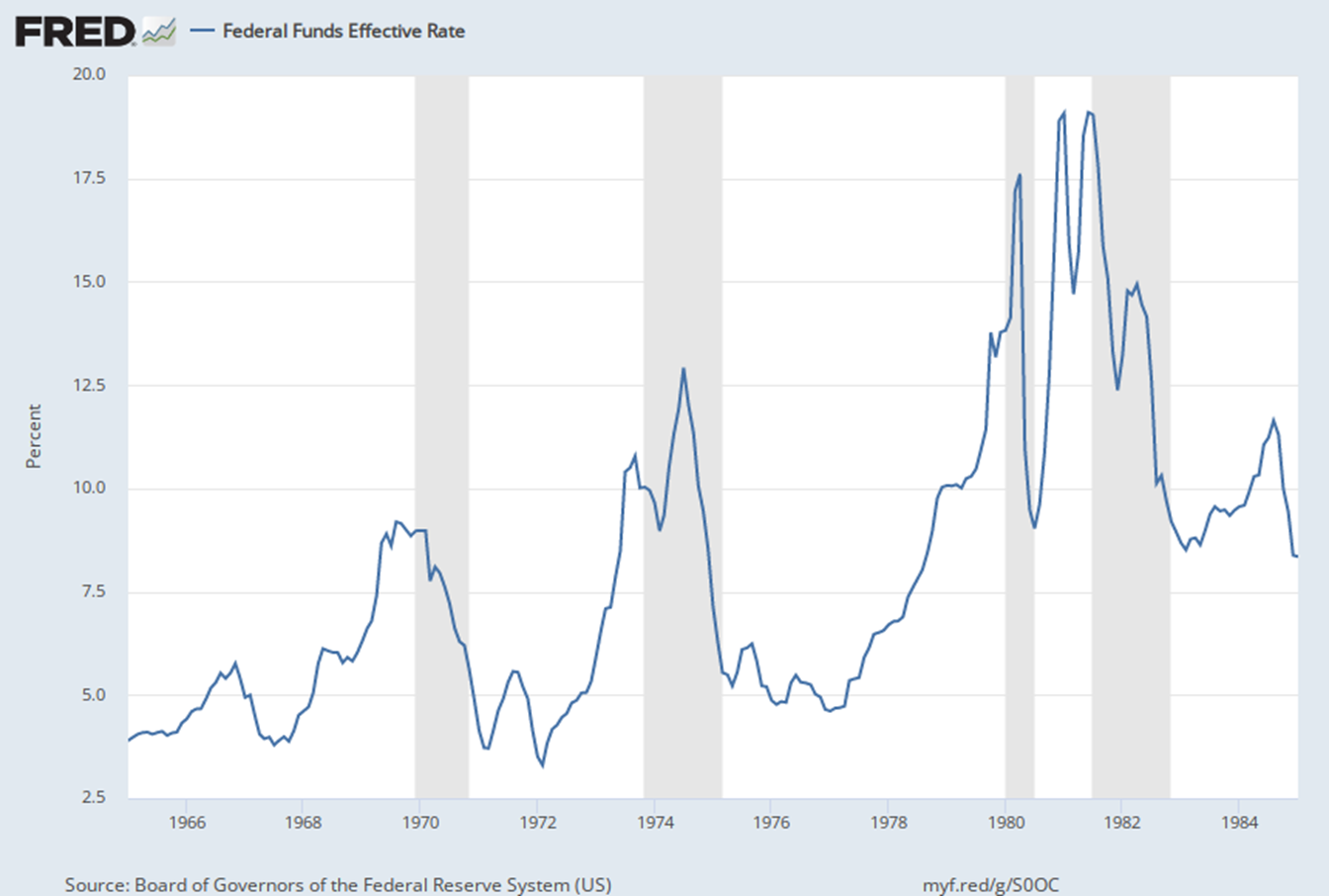

Lyndon Johnson is often blamed for starting the Great Inflation. Johnson’s Great Society social programs and escalation of the Vietnam War helped increase federal spending 57% during his second term. However, he refused to support tax increases to help offset those expenditures. He also encouraged the Federal Reserve, which was less independent than it is today, to use a light touch when setting rates, lest they cause a recession and damage his approval ratings.

After Johnson’s relative inaction on inflation, Richard Nixon’s August 1971 announcement of price and wage controls was welcome news to many. Their optimism soon faded.

Nixon chose to cap prices and wages because he was seeking reelection and had to do something about inflation, but feared that a rate hike would make him a one term president. Inflation fell to 3.3% in 1972. However, Nixon’s price controls also fueled shortages of many consumer goods and commodities. Nixon’s policies kept some prices much lower than they would have otherwise been — which increased demand for certain products, disincentivized firms from producing enough goods to meet that demand, and led to many empty store shelves.

Inflation crept back up to 6.2% in 1973 and polls showed that many Americans expected prices to soar once the caps were lifted. Sure enough, despite significant post-election interest rate increases, inflation hit 11.1% after the last of the price controls ended in 1974.

With unemployment rising and the nation in a recession, Gerald Ford’s “Whip Inflation Now” plan encouraged Americans to fight inflation by doing things like carpooling, turning down their thermostats, and planting gardens. The plan inspired many jokes that undoubtedly lifted spirits during a difficult time, but “W.I.N.” had little lasting impact on inflation.

Inflation Psychology

By the time Nixon took office, policymakers, economists, and pollsters had identified a growing wave of “inflation psychology.” Years of unchecked inflation caused many Americans to expect prices to rise even higher the following year. That mindset worsened inflation in a couple of ways.

First, it encouraged some to buy big-ticket items such as large appliances, cars, and homes sooner than they would have had they not feared being priced out by inflation. Reducing consumer spending is one way to lower inflation; fear-induced purchases only exacerbated the problem.

More importantly, inflation psychology shaped contracts. Manufacturers and their suppliers struck agreements that treated worsening inflation as a given. Workers demanded higher wages to offset future inflation; one year the United Mine Workers received a raise of almost 12% due to the perceived likelihood of increased inflation. As firms passed these costs on to their customers, inflation expectations became a self-fulfilling prophecy that drove prices higher.

Federal Reserve Chair Arthur Burns was painfully aware of the “wage-price spiral” and frequently blamed wage increases for driving inflation. However, he downplayed his own failure to give workers credible evidence that soaring prices would soon be a thing of the past. Policymakers repeatedly tried to cure inflation psychology by promising that the newest “solution” would fix the problem. Each time Americans saw a policy intervention fail to slow inflation — or offer temporary relief followed by price spikes — inflation psychology became more entrenched. By January 1980, Americans expected prices to rise 10.4% over the next year.

Tough Medicine

When Jimmy Carter took office in January 1977, inflation had recently fallen to 5.7%. As it began an all-too-familiar upswing, Carter and the Federal Reserve struggled to rein it in. When it came time to replace the outgoing Fed chair in summer 1979, Carter’s advisers warned him that choosing Paul Volcker could lead to Carter losing the 1980 election.

“My advisors were not at all in favor of selecting him,” Carter later recalled. “They knew that if I appointed him, he would institute the tough medicine of tight monetary policy, which would be difficult for the economy in the short run.” Nonetheless, Carter appointed Volcker, who implemented several rate increases before raising the effective federal funds rate to a record 17.61% in April 1980. For comparison, as of July 21, 2022, the federal funds rate was 1.58%.

Volcker’s rate hikes fueled a recession and an uptick in unemployment that helped doom Carter’ reelection bid. However, they also yielded positive results on the inflationary front. Subsequent interest rate increases topped 19% and caused a recession that lasted most of the first half of Ronald Reagan’s first term — but Volcker successfully brought inflation down to an acceptable level. More importantly, he kept it there.

Volcker’s actions made him a hero to many economists. Moreover, his actions forged a new consensus among macroeconomists about the importance of managing expectations in controlling inflation. Many economists had believed protracted recessions were necessary to reduce inflation, but Volcker proved that credible policy signals could end inflationary periods much faster.

History Repeats Itself?

Public inflationary expectations and the credibility of policy are important areas of focus for the Federal Reserve. Fortunately for current Fed Chair Jerome Powell (and the rest of us), polls show that the public expects prices to rise “only” 5.2% over the next year and 2.8% over the next five years.

Those expectations are heavily informed by the four decades of relatively low inflation the country experienced after Paul Volcker cured inflation psychology with a dose of tough medicine. However, as the Great Inflation made very clear, it is important for the Fed to show that they are serious about fighting inflation before public expectations change. Today's 75 basis point rate hike, coming as it does on the heels of June’s 75 basis point rate increase, should signal their intent.