The past 20 months have convinced some that our supply chains are broken and must be fundamentally overhauled. We respectfully disagree—broken systems do not move record amounts of freight during a pandemic.

However, the pandemic has shown that the system has room for improvement.

Before we can address the problems, we must identify them. This article contributes to that process by examining the role of demand uncertainty and unreliable sales forecasts in creating the issues we are experiencing this holiday season.

Record Demand, Historic Uncertainty

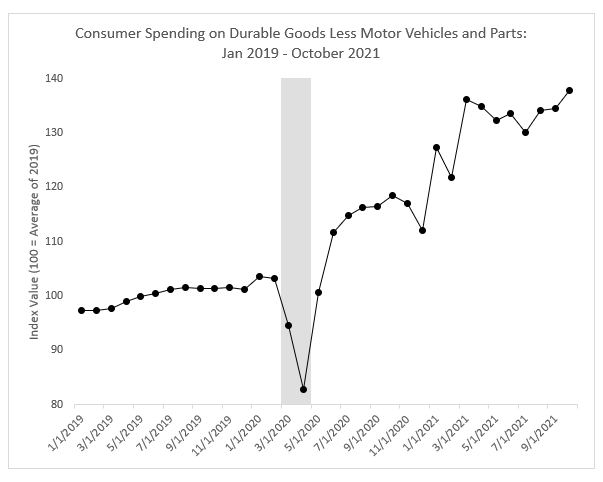

Anxious Americans spent much less than usual during the early weeks of the pandemic. Demand for nonautomotive durable goods bottomed out in late April, as shoppers spent 17% less than the previous year. The dip caused forecasting models - especially those that included trend forecasts - to predict sluggish sales. Managers planned accordingly and ordered less inventory, only to frantically try to increase their orders shortly thereafter.

In June 2020, Americans overcame their wariness about spending. COVID lockdowns limited their options for spending their expendable income, so shoppers spent enormous sums on goods like home appliances, consumer electronics, and furniture, bicycles, and toys. Between June 2020 and October 2021, nonautomotive durable goods purchases averaged 25.3% above 2019 levels.

Demand forecasting relies heavily on historic data, but that information loses much of its value during a once-in-a-lifetime global crisis. Many forecasting systems failed to translate the unexpected demand spike into useful forecasts. The uncertainty sent ripples throughout the supply chain, as companies at every echelon increased their orders and tried to make sense of rapidly rising, error-riddled forecasts.

Demand uncertainty was amplified as it made its way up the supply chain from the consumer. Consumer demand is smoother than firms’ order levels because people buy in relatively smaller quantities than companies order. So, large upstream orders made uncertainty even higher in the upper levels of the supply chain than in the lower echelons.

Uncertainty was worsened by a rash of stockouts. Low sales forecasts created early in the pandemic led to low orders that proved insufficient to meet the demand spike. As demand exceeded supply and many products went out-of-stock, most retailers’ forecasting systems offered little help. If a store sells 10 units of an item and runs out of inventory, they often have no reliable way of knowing if they would have sold 11 units that day or 30 units. Some forecasting systems will incorrectly tell the retailer they will sell 10 or fewer units the next day because they do not account for sales lost due to stockouts.

Companies often didn’t know what demand would be next month or next quarter. And even when they did, the combination of bad forecasts, inadequate spring inventory orders, and sustained record levels of demand created a capacity crunch that made ordering and quickly receiving goods a tricky proposition.

Caution in the Face of Uncertainty

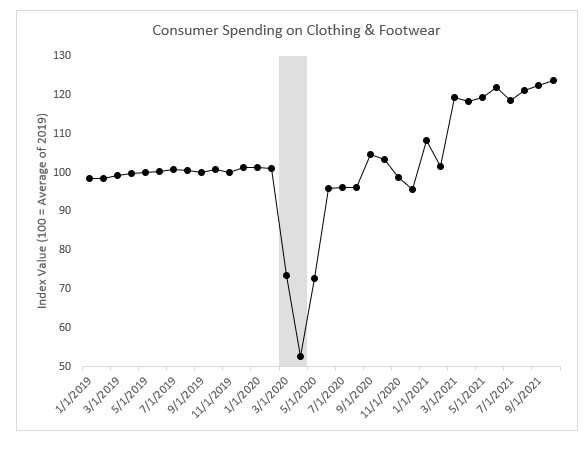

Clothing and footwear sales illustrate the uncertainty that has plagued the supply chain.

As many Americans began working from home, apparel spending plunged 48% below 2019 levels in April 2020. Then, just as quickly as demand fell, it roared back and surpassed 2019 levels in early summer. Spending fell back to 2019 levels in November and December, which are typically the biggest months for clothing and footwear sales (and hence are more difficulty monthly comparisons on a seasonally adjusted basis).

The roller coaster continued in 2021 as March’s third round of stimulus checks helped boost clothing and footwear spending far above 2019 levels. Demand stayed high from March to September, averaging 50.6% above 2019 levels. However, as the relief funds’ impact wanes, there’s no guarantee that sales will remain unusually strong through the end of the year.

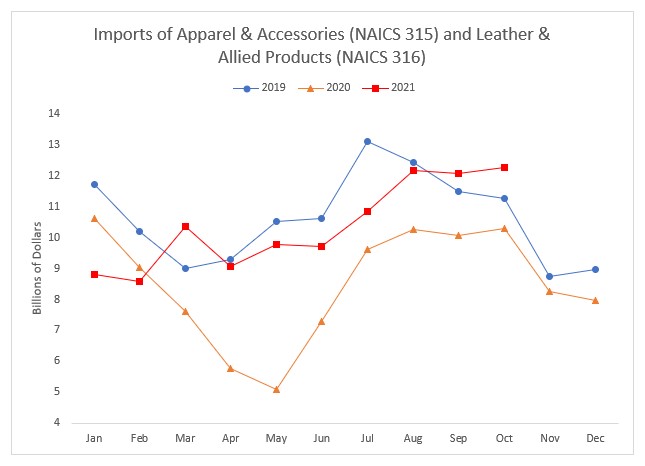

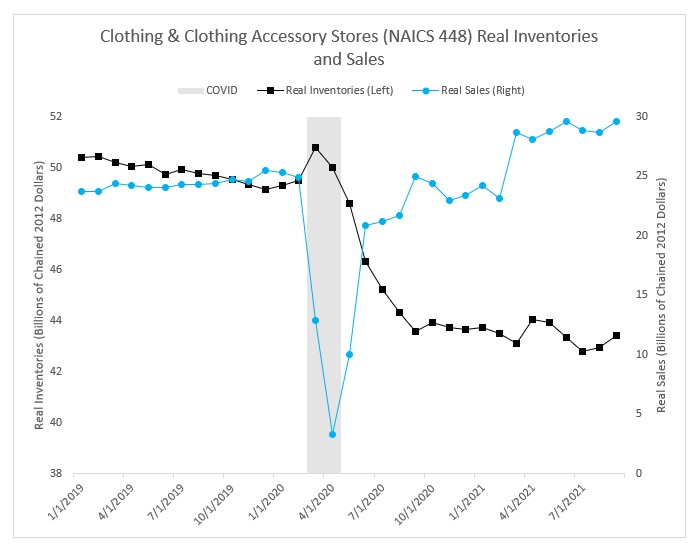

Retailers have been understandably cautious about replenishing their inventories amid such uncertainty. Imports and inventories are below 2019 levels, while sales are above 2019 levels. That formula is guaranteed to produce some stockouts over the holiday season, regardless of how soon the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach are unclogged.

Conclusion

Demand uncertainty and inaccurate forecasts have played a significant role in the supply chain issues we have experienced since March 2020. While firms’ ability to overcome those obstacles to meet record demand during a pandemic shows that the system works remarkably well, it is clear that there’s room for improvement in the areas of supply chain data analytics and visibility software.

It is perhaps unwise to make a prediction in an article about unreliable forecasts, but that’s exactly how we will conclude this article. Global disruptions are rare, technology moves rapidly, the pandemic has presented supply chain practitioners and researchers with plenty of “teachable moments,” and companies don’t want to disappoint their customers. So, we’re confident in predicting that supply chains will perform better during the next worldwide disruption.