Government contracts offer advantages and disadvantages for private business. The U.S. government can lend a degree of prestige to a business, proving the reliability of their product or service, and few clients can be as dependability a repeat customer than the government. These are among the reasons managers told Ellie Falcone, Walton College alumna and Assistant Professor of Supply Chain Management at TCU, Brian Fugate, chair and professor of supply chain management at the University of Arkansas, and Dean Emeritus Matthew Waller why they pursue these contracts despite their difficulties.

But managers also cite some significant drawbacks to working with the government. They feel it has “no financial skin in the game” unlike their private-sector clients, and government negotiators often offer “take it or leave it” contracts. Managers often describe the difficulty of fulfilling government contracts. Administration changes and funding lapses can also slow, halt, or change negotiations and fulfilment timelines.

For this reason, Falcone, Fugate, and Waller investigated whether there was an optimal balance of government contracts for businesses. Their research “Growing, Learning, and Connecting: Deciphering the Complex Relationship Between Government Customer Concentration and Firm Performance” was recently published in the Journal of Supply Chain Management.

To investigate the nature of this relationship, Falcone, Fugate, and Waller tested how firm size, absorptive capacity, and network embeddedness changed when the concentration of government customers tipped past the optimal balance. They intend their work to help firms decide the most effective strategy to balance risk and growth goals when pursuing government contracts.

The Reward for Striking a Balance

Despite the challenges associated with government contracts, there are significant incentives for suppliers to work with the government. First and foremost, governments can be a stable revenue source because no other purchaser can compete with the government’s size.

As part of their research, Falcone, Fugate, and Waller interviewed managers with suppliers that had contracted with the government. Those interviews showed that managers felt that securing and fulfilling a government contract was like certifying the legitimacy of their firm’s status, image, and reputation. Success also helped them attract future business.

A healthcare supplier told them that the first contract with the government is the hardest to get, and after that, the second goes much more smoothly. Likewise, after contracting with one agency, a metal parts company found that other government agencies reached out to work with them. Managers, however, also expressed surprise at how different and at times difficult it was to handle their government customers compared with their private customers.

As their interviews suggest, striking a balance in terms of government customer concentration is beneficial for firms and their long-term stability. Falcone, Fugate, and Waller’s work therefore helps managers find where exactly that lies given their firm’s particular characteristics.

Growing, Learning, and Connecting Play a Role in Improving Returns

To analyze those characteristics, the researchers combined data from Compustat, FactSet Revere, and the Federal Procurement Data System for the years 2010 through 2018 to test their hypotheses. They found that government customer concentration had an inverse-U shaped relationship with a firm’s return on assets (ROA). For example, the ROA from government contracts can be short-lived, as the firm’s market value increases but those increases erode over time. Also, having too few or too many government contracts create similar problems.

Their results also show that as firm size, absorptive capacity, and network embeddedness increase, the effect of government contracts on firm value becomes less dramatic. That is, larger firms, firms with a better ability to acquire and apply information, and firms that are more rooted in their networks can better navigate the difficulties that come from having more or fewer government contracts.

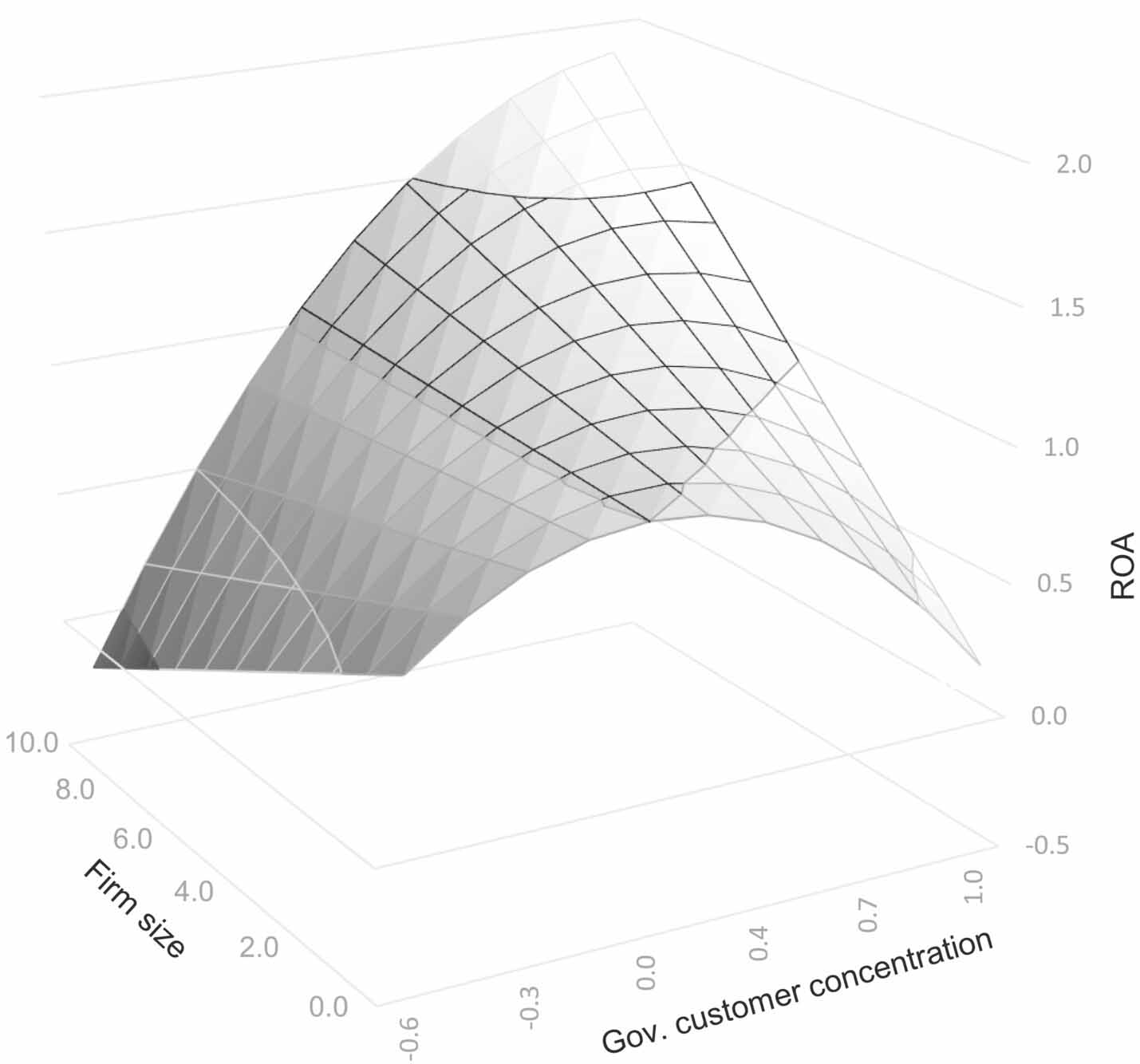

These traits did not, however, change ROA in the same way. Firm size did flatten the inverse-U shape, and in fact, the researchers say it nearly turned the relationship linear. Large firms could almost expect to see a linear increase in their returns on assets for each additional government contract they acquired. Of course, eventually each additional contract offers diminishing returns, and the researchers’ data shows ROA tapering off at the highest rates of government customer concentration.

If there is any drawback for large firms, it would be having too few government contracts. Larger firms saw slightly lower ROA than smaller firms with very few government customers.

Network embeddedness likewise flattened the inverse-U shaped relationship. Network embeddedness, or network centralization, measures a firm’s partnering choices and the stability of the relationships within the supply network. We might think of this as the other firms a business can depend on during an especially difficult contract. Despite its measurable effect, the researchers found that this relationship was less significant than the other two firm characteristics.

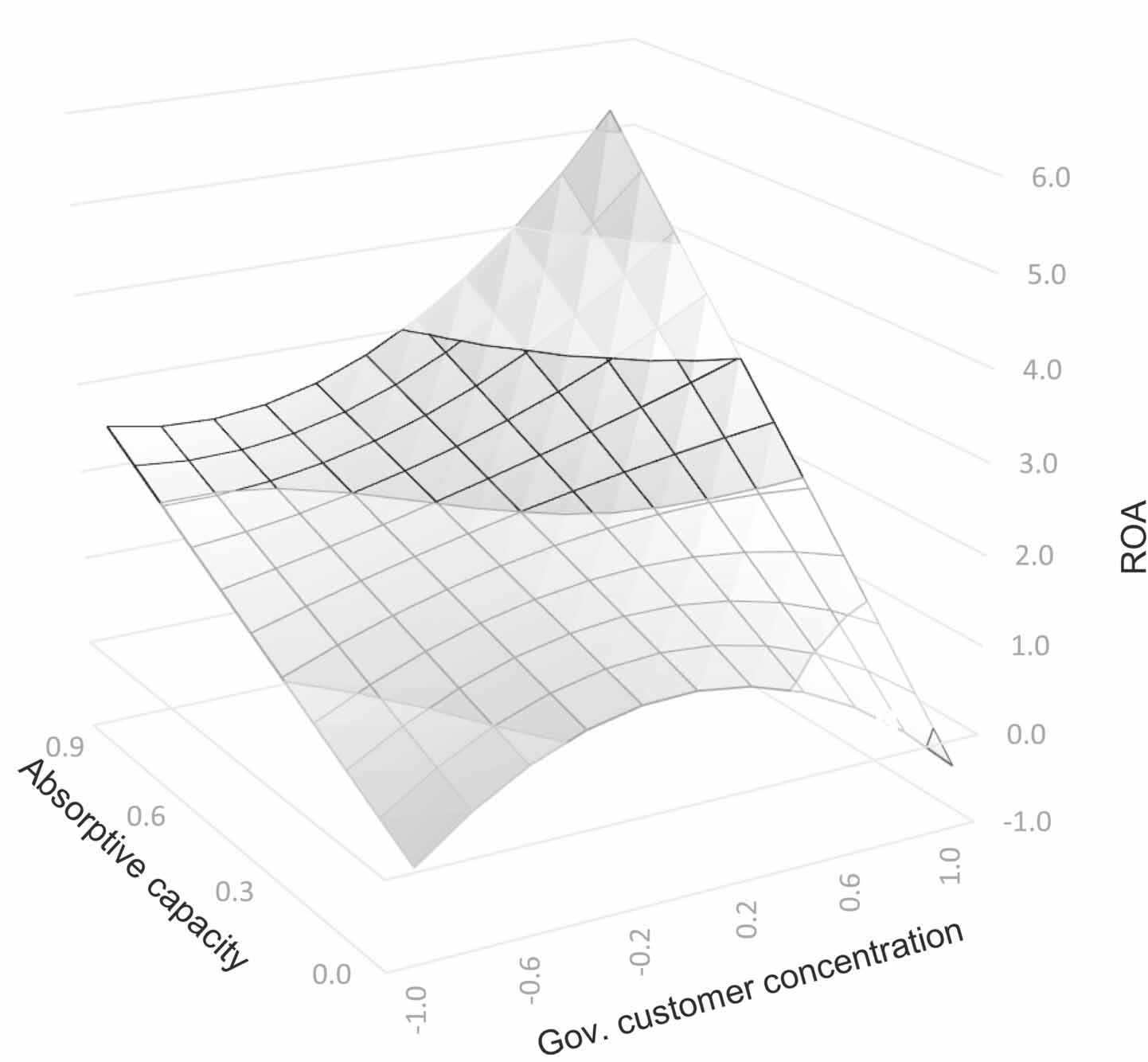

The most interesting results were the changes in ROA induced by increasing absorptive capacity, essentially a firm’s ability to learn over time. It did indeed flatten the inverse-U shaped curve, but at the highest rates of absorptive capacity it actually flipped the shape of the curve, creating a U-shaped relationship. That is, low concentration of government customers had a higher return than a moderate concentration, and the highest concentrations show exponential growth in returns. The researchers did not expect this relationship and hope future research can cast more light on this change.

Consider a Firm’s Characteristics When Competing for Government Customers

Government contracts have a nuanced influence: they can be a boon in the short term but can stymie long-term goals. Falcone, Fugate, and Waller work encourages leaders to consider key firm characteristics as they decide what kind of government customer strategy to pursue. They advise leaders “to prioritize internal growth” and that “expanding in size, such as through asset investment, appears to have the most significant impact as it helps to absorb and distribute risk,” especially as it pertains to high government dependance.

They show that an ability to benefit from government customers requires firms to be cognizant of their size, their ability to learn, and their partnerships within their own supply networks. This insight is important for both researchers and managers because doing business with the government has key benefits for stability and consistency, despite the complexities introduced by compliance standards, review processes, and reporting requirements.

Large firms could almost expect to see a linear increase in their returns on assets

for each additional government contract they acquired. Of course, eventually each

additional contract offers diminishing returns, and the researchers’ data shows ROA

tapering off at the highest rates of government customer concentration.

Large firms could almost expect to see a linear increase in their returns on assets

for each additional government contract they acquired. Of course, eventually each

additional contract offers diminishing returns, and the researchers’ data shows ROA

tapering off at the highest rates of government customer concentration.