Definitions should be straightforward and clear. At the very least, they should standardize usage and provide some semblance of clarity. I find myself echoing Jo in Little Women, with her favoring “good strong words that mean something.”

But that’s not always an option, though, with big concepts such as trust or with still developing phenomena. For those concepts, definitions proliferate with the tenacity of pokeweeds in Arkansas yards.

Add “privacy” to that list of hard-to-define concepts.

As Mary Lacity and Lynda Coon note in the introduction to Human Privacy in Virtual and Physical Worlds: Multidisciplinary Perspectives (Palgrave Macmillan, 2024), simply defining privacy is a daunting task. And, for them, that’s rather the point, as a “major contribution of this book is its ability to confront readers with both familiar and unfamiliar readings of privacy in all its complexity.”

Their collection grew from a statewide Honors Forum taught virtually in May 2023, which pulled students from two- and four-year institutions in Arkansas and five students from Amsterdam. Just as the forum pulled a variety of faculty from a wide range of disciplines, Human Privacy in Virtual and Disciplinary Worlds pulls insights from fields as wide as philosophy, architecture, computer science, library science, electrical engineering, and anthropology, as well as business disciplines, namely information systems supply chain management.

General readers will learn that privacy is markedly not a straightforward word that means “something,” but is instead a word that contains multitudes. It has had multiple meanings from antiquity to the present, remains a concept that encapsulates much disagreement and uncertainty, and will likely continue to be at the center of many a tense debate. Likewise, academics will be challenged to “broaden their research perspectives on privacy, [and move] beyond the limitations of a single disciplinary lens.”

Privacy and the Individual

Many of us – especially those of us raised and educated in the US or a similar tradition – will think of privacy in a tenor resembling Louis Brandeis’s famous espousal of "the right to be let alone.” Privacy is an ability to step back from the hustle and bustle of the world, to not have to let others intrude into your own affairs. Privacy is about control over what or who can access us and has an intrinsic value. Privacy is thus intertwined with questions about security, transparency, individual rights, and democracy itself.

But, and perhaps most importantly, as Sharon Mason notes, privacy is “an expression of autonomy, and the absence of any control over one’s own privacy threatens the conception of oneself as an individual self at all.” In certain cultures, privacy is not merely a right; it is a vital aspect of how we conceive of ourselves as individuals. To lose privacy means we lose our ability to regulate our interactions with others and signals that our lives may not be our own; no wonder that we view a loss of privacy “as a significant personal violation.”

Anthropologist Simon Hawkins, however, problematizes dividing our lives into public and private spheres. Privacy, for Hawkins, is a term that, while powerful and important, lacks “an inherent objective quality," meaning that anyone wishing to reckon with what the term means must also examine the idea in other cultures. Any “notions of privacy remain historically unstable” (as well as our notion of the “the public,” for that matter) because of the wide cultural differences that surround how privacy plays out in the wider world.

Privacy, Technically Speaking

Cybersecurity can never be far from any of our minds, regardless of whatever cultural differences may exist between us. Perhaps that is because hardly a month goes by without a major breach or attack occurring in the world. That’s because our personal identifiable information (PII), data that can identify or verify an individual or a group, is incredibly valuable. The global costs for cybercrime are expected to be $9.25 trillion dollars by the end of 2024, which would rank it as the third-largest economy in the world behind the US and China.

Farnell, Huff, and Cox helpfully delineate the most common types of attacks to obtain PII – Denial of Service, Man in the Middle, and spoofing attacks – but also note that privacy is “hard to preserve over the Internet....[because it] does not have predefined boundaries” and because servers could be distributed globally to improve speed or to add an additional layer of security. Equally helpful are their recommendations to organizations, which center on adopting “a well-developed and reviewed standard, such as NIST SP 800-53r5, and to individuals: using a non-attributable network, such as The Onion Router (TOR); using a privacy-specific operating system, such as the Debian Linux-based Tails OS; and having multiple online personas.

Schubert and Barrett continue this discussion of organizational efforts to safeguard privacy and focus on the effects cybersecurity breaches have on individuals and organizations alike. Connecting with Mason’s point about privacy and its role on our conception of self, they note that these breaches effect individual freedom, sense of dignity, relationships, and the ability one has to “live one’s conception of the good life....[that] privacy guarantees.” Further complicating matters for US citizens and consumers is that the US lacks a unified governance and enforcement mechanism at the federal level like the EU’s GDPR, at least not yet.

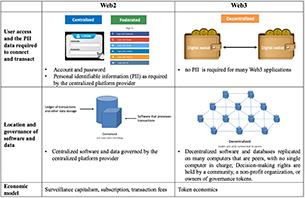

The role emerging technology may play in better safeguarding PII is the focus of Mary

Lacity and  Erran Carmel. Web3 lacks the centralized infrastructure of previous iterations of the Internet; instead, it is predicated on decentralization, as it sees a lack of central gatekeeper(s) as the best way to increase individuals’ privacy, power and cybersecurity. Thanks to distributed ledgers, digital wallets, and advanced cryptography, these emerging

technologies can “bake in” privacy concerns in ways that benefit users immensely.

Erran Carmel. Web3 lacks the centralized infrastructure of previous iterations of the Internet; instead, it is predicated on decentralization, as it sees a lack of central gatekeeper(s) as the best way to increase individuals’ privacy, power and cybersecurity. Thanks to distributed ledgers, digital wallets, and advanced cryptography, these emerging

technologies can “bake in” privacy concerns in ways that benefit users immensely.

Another solution is multi-party computing (MPC), which allows trusted parties to answer questions without revealing specific, personal information. As Conway and Garimella note, while MPC "promotes privacy, it is not computationally efficient.” Garimella and Conway also examine the role that zero-knowledge proofs (ZKP) can have in promoting privacy and protecting PII. ZKPs are privacy-enhancing algorithms that essentially allows one party to prove something (such as their identity) without have to disclose the details of their identity. ZKPs are more computationally efficient and require lower amounts of trust than MPC scenarios, they still require more computational resources than some “real-time, high-volume scenarios” may allow.

As is the case with any effort to safeguard privacy, these technical solutions create tradeoffs between cost, performance, and security. The trick is determining which tradeoffs are acceptable and which are not.

Privacy, Broadly Speaking

Returning to the instability Hawkins believes central to any attempt to define privacy, the remainder of Human Privacy in Virtual and Disciplinary Worlds focuses on how different intellectual disciplines understand the concept. For example, Marlon Blackwell, professor of architecture and principal at Marlon Blackwell Architects, notes that “comfort is a big driver of ideas about privacy....Architecture accommodates and facilitates privacy and comfort. Comfort informs how we think about space, how it’s used.” As such, it should come as no surprise that a key design principle of his is the creation of private moments in public spaces, of “making spaces that can be used for fellowship and for solitude.”

What does privacy look like when confidentiality is not absolute? D. Micah Hester explores this notion in detail, noting that the confidentiality of patient information in healthcare is challenged by the many diagnosticians, therapists, social workers, chaplains, clerks, insurance providers, and others who routinely must access this information. This doesn’t even account for “permissible breaches” of privacy – reporting communicable diseases, court-ordered disclosures, suspicions of abuse or criminal activity, and instances where imminent harm is likely to occur. The best course of action for providers and institutions is maintaining vigilance in their attempts to prevent breaches while also being transparent to participants and patients about how widespread use of technology will likely create privacy losses.

Just as there is no international standard or governing body regarding online privacy, “there is no one approach to archival privacy in North America; nor is there a single international legal system.” Windon and Youngblood examine privacy in a discipline where “access is the primary goal, but that privacy must be respected.” The lack of a singular legal approach puts the ethics of the archivist in a central role, noting that “a greater attention to privacy considerations does not compromise the central access mission of archives – it just makes things a bit more complicated.” A decision-tree approach helps archivists navigate these competing interests.

The final chapter of the collection focuses less on consumers’ and citizens’ PII data and instead on employees. Namely, what sort of privacy do we want or need at work? Scott, Waller, and Fugate argue that while organizations that “observe various aspects of both customer and employee...perform better,” privacy concerns are not alleviated by higher levels of performance. In fact, differences in personality, values, goals, work characteristics, and organizational cultures and climates all can affect how employees respond to electronic performance monitoring systems. Striking a balance between organizational, employee, and consumer needs is key.

Implications and Takeaways

As Lacity and Coon note, privacy remains – and perhaps always will remain – a moving target, especially when we consider how cultural contexts and location affect our understanding of it. There is a part of me that would agree with Judith Jarvis Thomson’s statement from almost fifty years ago: “The most striking thing about the right to privacy is that nobody seems to have any very clear idea about what it is.”

And yet there is also a part of me that says a striving for clarity is beside the point. Perhaps that’s what this multidisciplinary collection on privacy has taught me more than anything else. The point is safeguarding privacy and making sure that despite the conflicts between individual and group, what legal jurisdictions govern which actions, and so forth, that measures be taken to bolster individual privacy for citizens, consumers, employers, and users.

In the past decade, worries about surveillance capitalism, loss of human autonomy, and a demand for ever-higher levels of efficiency and productivity have abounded. The digital – and physical – future in the making seems to be on that “infringes on privacy and private space, often under the guise of the public good and capitalist efficiency.”

But this doesn’t have to be the case.

The choices we all make matter.

If privacy is important, it is up to citizens, users, and consumers to determine how we can hold parties with whom we act accountable. Trusting that technology providers or other powers that be will do the “right thing” may result in what users want, or it may simply result in a further entrenchment of a status quo that sees individual privacy as a secondary concern. The choices we make – or the Hobson’s choices we refuse to entertain and instead push back against – could very well be the foundation of a reordering of society that bolsters individual privacy.

Click here for an Ozarks at Large interview with Profs. Coon and Lacity on their book.

understand the concept. For example,

understand the concept. For example,