Temporary Supply Chain: How a Global Group of Volunteers Rallied to Address the PPE Shortage for Hospitals in the United States

April 16, 2020 | By John Kent

Spring Break typically finds me in China, but this year I was relaxing on the farm – until an unexpected opportunity arose to contribute to a unique collaboration that now is helping supply hospitals with nearly a million dollars’ worth of much-needed equipment in their fight against COVID-19.

One of my regular trips to China throughout the year always overlaps with Spring Break so that I can maximize my work as director of supply chain China initiatives for the Sam M. Walton College of Business at the University of Arkansas, while minimizing the conflicts with my teaching.

With that trip cancelled this year because of the pandemic, the new plan for the off week included hiking, riding ATVs and watching the newest lamb flock hop around the pasture at our secluded farmhouse near the Buffalo National River. Then a series of discussions on the social media app WeChat led to a seemingly simple idea that took on a complex life of its own and grew to involve, at some level, more than 100 people over the next few weeks.

This ad-hoc project, as complex and demanding as it has been, proved far more fulfilling than just about anything I’ve ever been involved in. And the behind-the-scenes story is worth sharing because it exemplifies the power of global collaboration during trying times to solve real-life supply chain issues for people in need.

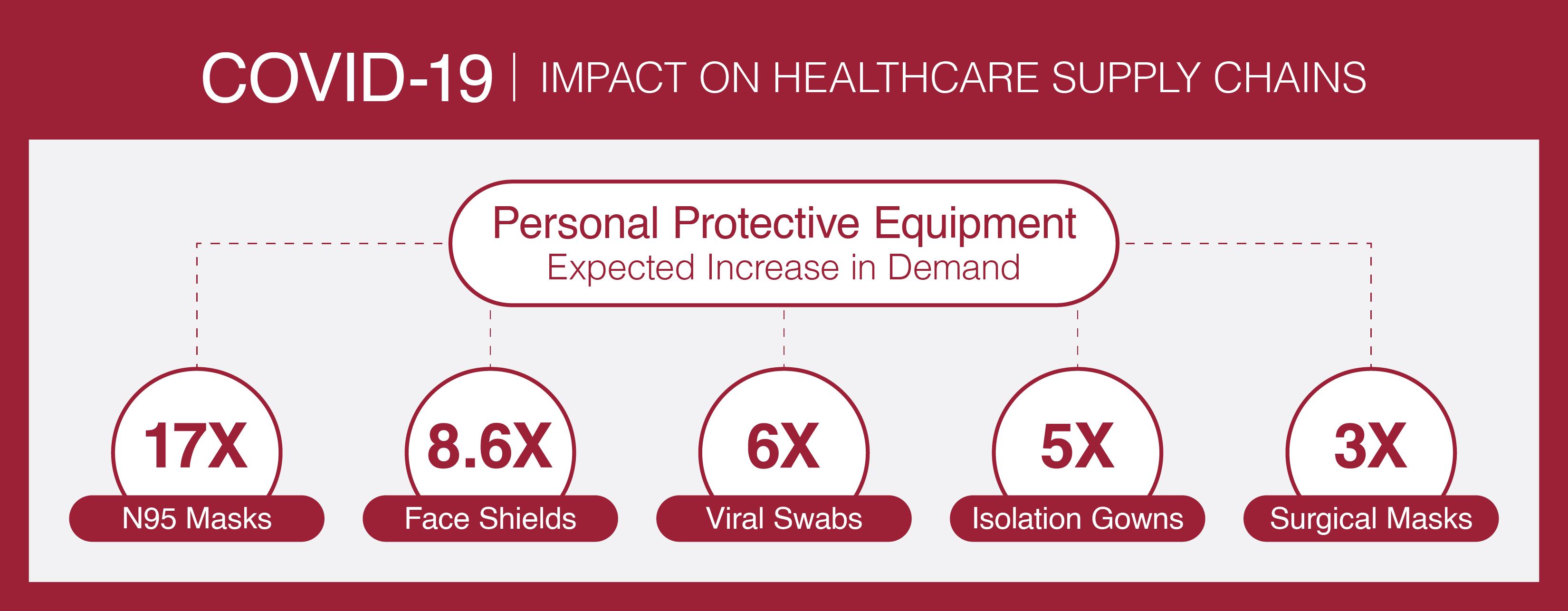

It began with discussions about a three-letter acronym that once was little-known outside of health-care circles and now seems destined to enter Webster’s dictionary. PPEs (personal protection equipment) include a wide range of products – N-95 masks, Level 2 gowns, Level 3 surgical masks and Level 2 intake masks, just to name a few. With the global demand for these supplies spiking, normal supply chains were disrupted and, in some cases, had become dysfunctional. Yet, suppliers in China were using WeChat to advertise all sorts of available options, complete with product descriptions and photos.

A few friends and I who are active on WeChat began wondering if we could combine our experiences and expertise to help provide hospitals and essential workers in America with an alternative supply chain to access products sourced from China. So, we set up a video call to explore ideas. I represented the Supply Chain Management Research Center at the University of Arkansas, while others represented the George H.W. Bush Foundation for US-China Relations (Robbin Goodman) and the Arkansas Association of Asian Businesses (Yang Luo-Branch). This group of volunteers began talking almost daily and other members of those organizations joined in, including the Bush China Foundation’s David Firestein and Euhwa Tran; American Logistics Aid Network (ALAN) Kathy Fulton and Roger Woody; and the Walton College’s David Dobrzykowski, an associate professor of supply chain management with an expertise in the health care industry.

Consortium Partners

George H. W. Bush Foundation for U.S.-China Relations

- Robbin Goodman, Director of Business Programs and Corporate Affairs

- David Firestein, President and Chief Executive Officer

- Euhwa Tran, Chief Operating Officer

Sam M. Walton College of Business Department of Supply Chain Management

- John Kent, Ph.D., Director, Supply Chain China Initiatives

- David Dobrzykowski, Ph.D., Associate Professor, Supply Chain Management with Health Care

American Logistics Aid Network (ALAN)

- Kathy Fulton, Executive Director

- Roger Woody, Board Member

Ad Hoc

- Yang Luo-Branch, Ph.D., President, Arkansas Association of Asian Businesses (AAAB) and board member Bush China Foundation

- Keith Lomason, President, Lomason Consulting, Shanghai, China

We quickly began addressing key questions – like, Do we really need to create a new supply chain option when they already exists? – which led us to identify the key challenges and needs. We realized that if we couldn’t add distinctive value, we needed to leave this challenge to those already taking it on.

David’s contacts with large hospital systems and global suppliers helped us understand the “normal” process and why it was stressed under current conditions. Most hospitals traditionally ordered these supplies through a third-party provider that handled all the transactions with overseas firms and the logistics to get the products from there to here, usually on a cost-effective container ship – literally a slow boat from China. Now hospitals needed a faster process, but still one they could trust. And, oh yeah, their budgets were being stretched thin by a variety of demands related to the crisis.

Here’s the supply chain problem in a nutshell: The market was going crazy.

OK, maybe we need a bigger nutshell: Countries and hospitals all over the world were competing for PPEs like never before. China, meanwhile, was emerging from its economic shutdown and resuming its place as the primary producer of these products. But traditional suppliers were overwhelmed, so most requests resulted in back orders. U.S. distributors, who make their money by placing and managing orders, were swamped with requests and actually started telling hospitals to “reduce consumption.” New suppliers were springing up almost overnight and some manufacturers of non-PPE products were converting their operations to meet the rising demand. But not all of their products met FDA requirements and some of the new suppliers were flat-out dishonest.

Hospitals in the United States had little to no experience buying direct from China. They needed help navigating the logistics and purchasing of these orders, but most of all they needed assurances that the suppliers in China had been vetted, that the orders could be verified and the money transfers would be secure.

While we knew existing firms in the United States were positioned to work with traditional suppliers in China, we realized we might play a role in vetting newer suppliers and assisting with the purchasing and logistics. In this regard, Keith Lomason became a key addition to the team. Lomason is an expat whose 25 years of experience sourcing auto parts in China and Marine training allowed him to quickly adapt and establish boots on the ground in Shanghai and Shenzhen to qualify new sources of PPE.

Meanwhile, we identified an initial set of hospitals from which we could better understand demand and canvased America to understand what other players in the market were doing so we could take advantage of potential synergies by working together. We spoke with CEOs, purchasing executives and mid-level management from hospitals in several states; leaders from trading companies, global logistics companies and suppliers; bankers in the United States and in China; and leaders of nonprofit foundations representing both countries. We even talked with two investors in San Francisco who claimed to represent hospitals in Northern California and were looking to order a millions of masks and thermometers.

Over the next two weeks, two hospital systems emerged as ready to make orders. Lomason, meanwhile, put together a team in China that took our initial set of around 60 interested PPE suppliers and narrowed that to about 10 that claimed to have the proper FDA certifications to manufacture and ship medical products to the United States. His team would literally go to the factory floors to vet the suppliers and their products, and they will follow those products until they are loaded on the airplanes that will fly them to the United States. We also engaged a trading company to manage international funds transfers, including payments to PPE suppliers and door-to-door transportation providers.

Keep in mind that we were making all of these plans in a highly unpredictable environment with an emerging supply chain team that had never worked together. We were trying to develop trust in few days in an extremely risky global marketplace with countries, states and hospitals all competing for scarce resources. “Not for the faint of heart,” “the wild west,” and the “targets are moving and the ground is shaking” were all metaphors used in our conversations.

At the start of the third week, April 6, I received a care package from one of my best friends in Beijing – a DHL delivery of 100 surgical masks and 20 FN-95 masks. PPE masks for me and my family. At the same time, we were closely monitoring our first two orders – one from Mercy Health, the St. Louis-based hospital system with more than 40 facilities and more than 40,000 employees, and the other from Texas Tech University Health Science Center, which was ordering for itself as well as for the Texas prison system.

The combined order was for more than 500,000 items – mostly N-95 masks, surgical masks, face shields, and isolation gowns – with a price tag of just over $1 million.

Almost immediately, there were glitches. A field on an electronic banking form was too small for the entered information, for instance, so a disappearing company prefix cost us a day, which, because of the rising price of materials used to make masks, cost us several thousand dollars. But the transactions eventually went through and the waiting began.

You might think the orders would be delivered to the hospitals’ respective distribution centers within a few days since our new supply chain is using airfreight instead of ocean carriers; however, the total order cycle from placing the orders to delivery is expected to be about 14 days. The major steps in the global supply chain include:

- Determining the items and checking market prices

- Placing the order via the trading company

- Making an international wire transfer of funds

- Placing the order for transportation services and items with the manufacturer (multiple manufacturers and transportation providers all need to be coordinated.

- Preparing and qualifying the order for shipment

- Ground transportation from the manufacturer to the international freight airport

- Scheduling the next available airfreight to the United States and, hopefully, to a city near the hospitals

- Qualifying and clearing government export requirement for the order at the airport

- Air transportation, which is about 13 hours from China to the United States

- Clearing customs in the U.S. (remember, these are medical products and require additional government agency checks

- Time to load the trucks for ground transportation to the hospitals’ distribution centers, and

- Receiving the shipments into the hospital systems.

If the new supply chain functions as planned, the hospitals systems will begin to receive the PPEs the week of April 20. After that, the products still need to be delivered to the front-line clinicians at various hospitals. In the meantime, our volunteer group is continuing to vet suppliers and work with other hospitals on new orders in what, to me, has been an amazing display of supply chain innovation, entrepreneurship, public/private partnerships, and people from the United States and China working together for the common good.

For a more detailed look at the health care aspect of this project, check out the companion article by my colleague David Dobrzykowski.