John Dominick learned a lot from driving a combine harvester in his youth. Namely, that he didn’t want to do that for the rest of his life.

Harvesting oats was the worst. The chaff would get on his skin and itch like crazy. It was his first job and one that made him realize he favored business over working outside in the elements.

But that’s not to discount farmers. Far from it.

“I like farmers,” says Dominick. “They’re probably the most honest sort you will find. They work with the soil and that’s about the greatest thing you can do.”

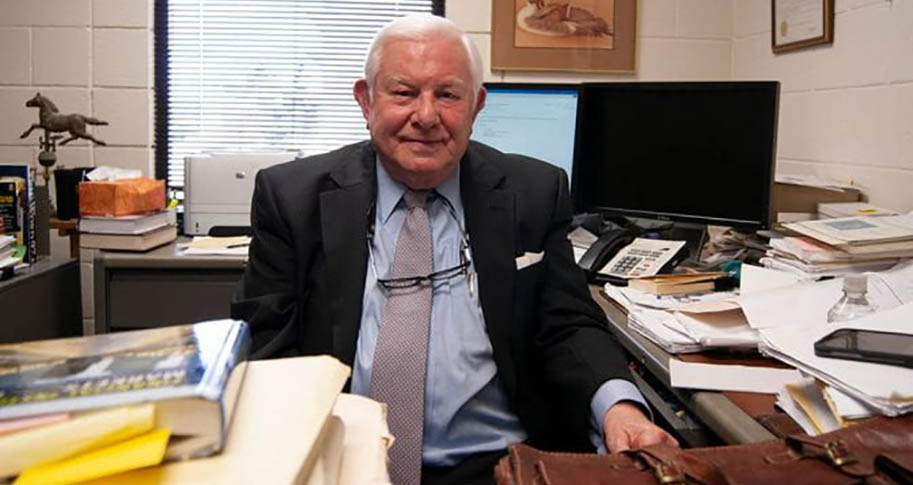

For the past 49 years, Dominick has served as finance professor for the Sam M. Walton College of Business – long before the Walton named was attached to the University of Arkansas’ business program.

Dominick grew up surrounded by agriculture. His father had a cotton farm in Mira, Louisiana, a rural community in the extreme northwest corner of the state, and taught Dominick the importance of work ethic – one that combined honesty and elbow grease in doing the job right.

He carried that ethic to the Louisiana Tech University in Ruston, where a professor there saw promise in the young economics and finance student. When that professor relocated to the University of Alabama, he persuaded Dominick to join him. “He was the only person I knew in Alabama,” Dominick recalls.

At age 22, Dominick taught business as a grad assistant, earning a master’s degree and a Ph.D. in the process. He joined the faculty of the University of Alabama for two years. He was then employed by Louisiana Tech University to start a program in commercial banking. Five years later, an advertisement for a professorship at the University of Arkansas piqued his interest, one that held the Arkansas Bankers Association chair.

He applied and, in 1970, Dominick joined the business faculty at the University of Arkansas. Richard Nixon was president. The United States was at war in Vietnam. The university had a student enrollment of about 12,000 (today it’s about 27,000). He says the offices for the university’s business college were in what is now Gearhart Hall, which was not air conditioned and were partitioned with pegboards – a far cry from the modern facilities at Walton today.

In his nearly 50 years at the University of Arkansas, he saw the business college relocate to a single building on McIlroy Avenue (built in the late 1970s) and expand to three more: the Donald W. Reynolds Center for Enterprise Development, Willard J. Walker Hall and the J.B. Hunt Transport Services Inc. Center for Academic Excellence.

He printed his exams on a mimeograph machine, a process that involved typing on a typewriter containing a sheet of paper paired with a carbon sheet to transfer the text. The carbon sheet was then placed in a machine with an ink-filled roller to transfer the content to multiple copies. “If you made a mistake typing, it was bad news,” Dominick says.

Dominick briefly served as an interim department chair for two years in the late 1990s, but he knew that role wasn’t for him. Instead, he continued to teach the principles behind banking and never considered doing anything else. “I like what I do,” he says.

“That’s a great thing,” says Gus Rusher, a former student and retired banker living in Fayetteville. “It speaks highly to his ability to stay with one institution that long. He had literally thousands of young people come through that he’s instructed.”

Rusher recalls that Dominick was always prepared for class and open to discussion if any students needed to meet with him. Even after many of his students graduated, they continued to learn from Dominick in classes he taught for banking professionals, many of them new to the field, through the Arkansas Bankers Association.

As a result, Rusher stays in contact with Dominick and counts him as a good friend.

While Dominick has inspired a countless number of students, he also draws inspiration from his peers. The first person he names is Marketing Associate Professor Dub Ashton, another longtime Walton faculty member who continues to teach students despite health challenges. “If Dub can do it, by golly, I can do it,” Dominick says.

There’s also Pu Liu, professor and chair of the Department of Finance. “If you look in the dictionary for the word ‘gentleman,’ and it doesn’t say ‘Pu Liu,’ you’re looking in the wrong dictionary,” he says.

In addition to teaching, Dominick serves on the board of directors for both White River Bancshares and Signature Bank of Arkansas, where his former student, Gary Head, serves as chairman, chief executive officer and president. Head previously was president of McIlroy Bank & Trust in Fayetteville, and then Arvest of Fayetteville, before he left to form Signature Bank.

Head says his initiation into banking policy happened in 1982 when, as a University of Arkansas student, he helped Dominick inform voters about a proposed interest rate control amendment.

“He was very knowledgeable,” Head says. “He probably taught about 90 percent of the bankers in Arkansas.”

When Head graduated, Dominick helped him get interviews with two banks, one of them being McIlroy Bank, which, at that time, was the oldest bank in Arkansas. Head was hired and eventually became bank president when he was only 39 years old. When Head formed Signature Bank, the first person he considered to serve on its board of directors was Dominick, who’s chair, by then, had shifted away from the Arkansas Bankers Association and replaced with the J.W. Bellamy Chair for Banking and Finance, posing no conflict of interest. “Now my mentor is my boss,” Head jokes.

Head continues to seek his input and just recently hired an employee at Dominick’s recommendation, he says.

“I don’t know of very many banks that ‘Dr. John’ doesn’t have his fingerprints all over in this state,” Head says.

Dominick will teach his last semester in fall 2019, one that will sure to be bittersweet. But he has a wife he adores along with children and grandchildren, and he looks forward to spending more time with them.

“That keeps you going,” he says. “That keeps you optimistic.”

As for how he’ll be remembered, Dominick doesn’t dwell on it.

“My legacy will be with the bankers I have taught,” he says. “Some will remember me. Some will not. You’re basically a number.”