Rhetorical Situation

A rhetorical situation is any circumstance in which one or more people employ rhetoric, which is the attempt to persuade, or convince, an audience either (1) that something is true or (2) to follow a certain course of action. Speakers and writers who use rhetoric are called rhetors. There are six components of any rhetorical situation:

- Exigence: what motivates the rhetor to make an argument.

- Rhetor: the person delivering the argument, either verbally or in writing.

- Argument: the conclusion or recommendation the rhetor seeks to make.

- Audience: those whom the argument is intended to persuade.

- Subject Matter: the topic (or topics) relevant to the argument.

- Constraints: factors affecting how the audience receives and interprets the argument.

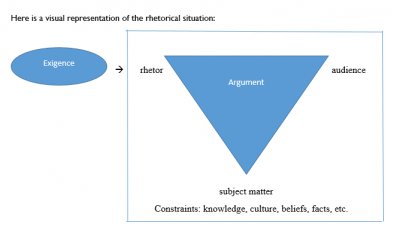

Here is a visual representation of the rhetorical situation:

Note: Argument is represented as a triangle because the background of the rhetor, the background of the audience, and the subject matter all determine how the rhetor chooses to shape the argument.

This resource was prepared by the Business Communication Lab at the Sam M. Walton College of Business

All rhetorical situations originate with exigence. The exigence is what motivates a rhetor to argue in the first place. Why does the rhetor need to make this point? What will this argument do for the world?

Examples of exigence:

A congressman delivers a speech arguing that we need stricter gun control. The exigence is that the congressman believes stricter gun control will lead to less gun violence.

A pastor writes and delivers a eulogy at a funeral. The exigence is that it is customary to reflect on a deceased person’s life and accomplishments.

A defense attorney argues before a jury that her client is innocent of murder. The exigence is that it is the defense attorney’s job to ensure that her client—even if guilty—receives a fair trial.

All rhetors write or speak for an audience, the body of listeners or readers—real or imagined—that the rhetor is arguing to. There are two kinds of audience:

- Immediate audience: the individuals literally listening to or reading the rhetor’s argument. For example, in the president’s State of the Union address, those hearing the address (representatives, senators, people watching from home, etc.) are the president’s immediate audience.

- Mediated audience: the individuals for whom the argument is intended. These individuals may or may not actually listen to or read the rhetor’s argument. For example, in the State of the Union address, all American citizens—even those not tuning in to the address—are the president’s mediated audience.

Rhetorical situations are based on the relationship between the rhetor, the audience, and the subject matter, but they are also based on various constraints that not only affect how the rhetor argues but how the audience interprets the argument. Common constraints include:

- Knowledge of the rhetor and audience about the subject matter

- Example: A rhetor alludes to a quotation from the Declaration of Independence, a document which she strongly believes the audience will recognize.

- Beliefs held by the rhetor and audience about the subject matter

- Example: A rhetor suspects that her audience consists primarily of devout Christians. Knowing this, she argues against tattoos by citing a passage from the Bible condemning them.

- Culture of the rhetor and audience

- Example: A rhetor suspects that her audience consists of very patriotic U.S. citizens. She therefore argues that supporting the war effort is “part of being an American.”

- The time of the argument

- Example: A rhetor has a hard time stirring the emotions of the audience at 7:00 a.m.

- The timing of the argument (the Greeks called this kairos—the idea that a good rhetor will know when it is the right time to make an argument)

- Example of good kairos: Following a fatal school shooting, a rhetor argues for stricter gun control laws.

- Example of bad kairos: A rhetor makes a tasteless joke too soon after a tragic event.

- The place of the argument

- Example: A rhetor delivers a compelling argument, but the audience is too distracted by the sound of nearby construction machinery to pay attention.

- Relationship between rhetor and audience

- Example: A political candidate gets a warm reception in her home state, but when she gives speeches in other states, the audience is more hostile toward her.

Abraham Lincoln delivers his second inaugural address upon being reelected president during the American Civil War.

Exigence: It is customary for the president of the United States to deliver an inaugural address upon being elected or reelected to the office. In addition, as the leader of the nation, Lincoln must attempt to heal the “wounds” caused by the American Civil War and attempt to bring North and South back together.

Argument: The United States should finish the war with “malice toward none.” Citizens should work toward recovery instead of blaming each other for the war.

Rhetor: Abraham Lincoln (Republican), who has just been reelected to his second term

Immediate audience: Those in attendance of the address

Mediated audience: All Americans, even those not in attendance

Subject matter: The American Civil War, slavery, religion, recovery

Constraints: Facts (e.g., the participants in the war, the death toll, the major battles), beliefs (e.g., about the cause of the war), time (March 4, 1865), timing (near the end of the Civil War and approaching the Reconstruction period), place (in front of the Capitol Building in Washington, D.C.), relationship with audience (both Union and Confederate).

These are all factors Lincoln has to consider as he writes and delivers his address. In the address, Lincoln makes several references to culturally important events or texts (such as passages from the Bible) that he knows most of his audience members—both those from the North and from the South—will understand. This allows him to craft his address in a way that both sides will appreciate, which is important toward his purpose of reunifying the nation.

General Business Communication

Sound less like a student and more like a professional. Make your writing logically sound, persuasive, and concise by following these tips.

Research & Citations

Save time and energy in research and writing. Follow these tips and watch your research process become more targeted, efficient, and rewarding.

Grammar & Mechanics

The best communicators build credibility through polished, purposeful writing. Compose admirable text by following these essential language guidelines.

ESL Student Guides

American business culture is full of unique language, customs and expectations. Use these resources to build skill and familiarity with the conventions of academic and professional environments.

Oral Communication

Are you experiencing trouble writing or delivering a speech? Use these resources to develop confidence and poise as a public speaker, whether in the classroom or the professional world.