Given the increased prices consumers are paying for food consumed at home — up 10.6% as of December 2021 from January 2020 per the Bureau of Labor Statistics — it is natural to question whether food manufacturers are abusing market power as argued in a recent essay in Time magazine.

At first glance, market power explanations are appealing since some sectors of food manufacturing are highly concentrated. For example, in breakfast cereal manufacturing, the four largest firms accounted for 81.8% of the value of shipments based on the 2017 Economic Census. Likewise, in the animal (except poultry) slaughtering sector, the top four firms account for 63.4% of the value of shipments.

However, the market power-focused Time piece overlooks key evidence that food manufacturers are not unduly increasing prices. We raise this issue in hope of helping policymakers understand the true source of the inflation we are experiencing so they may effectively combat it. We have previously shown that supermarkets are not price gouging consumers. Our analysis suggests food manufacturers are likewise not profiteering.

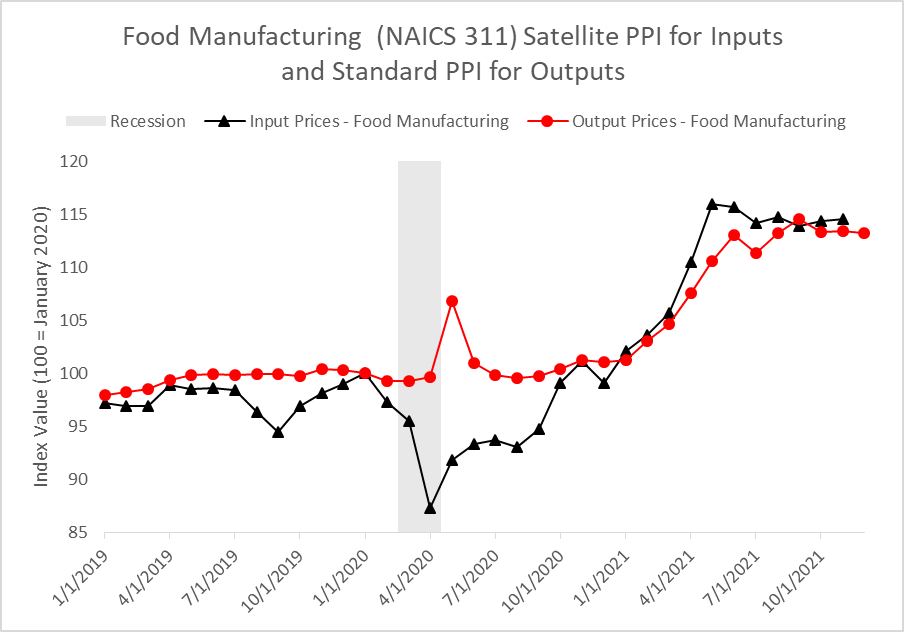

Problem 1: Output prices for food manufacturers have risen in tandem and in equal proportion to rises in input prices.

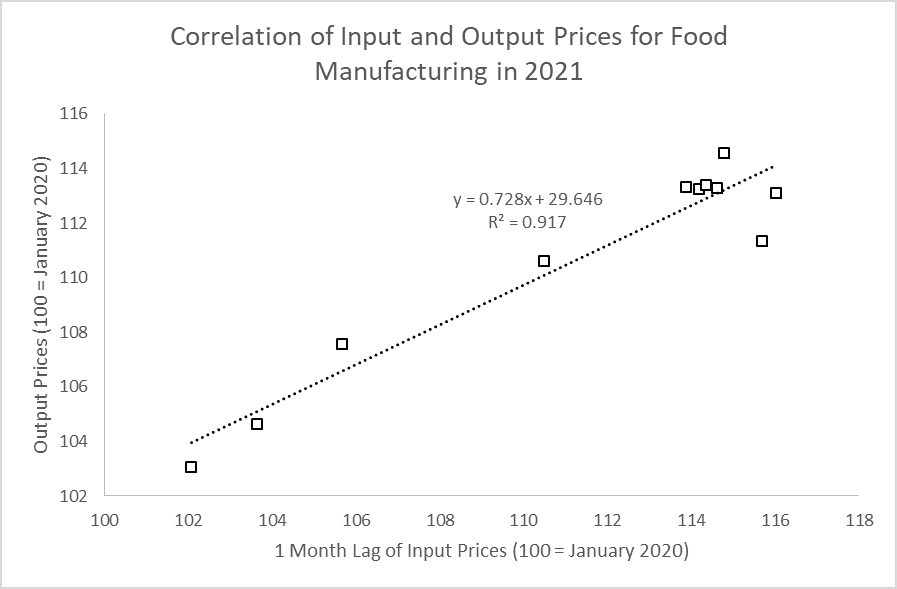

It is now straightforward to observe how most industry’s input costs change thanks to the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ (BLS’s) new satellite producer price index program. This program measures the change in domestic and foreign input costs excluding labor and capital equipment. Below we have plotted the change in input prices for food manufacturers as well as the producer price index showing the change in their output prices. In 2021, the changes in input and output prices are closely aligned. In a second plot, we show the linear trend between input prices that are lagged one month—firms tend to delay increases in output prices until their input prices have increased—and output prices. The two series correlate 0.96. Furthermore, you must then factor in that separate BLS data shows the average $/hour for all employees has risen 8.7% as of December 2021 from January 2020. As the Annual Survey of Manufacturers indicates payroll represents 9% of food manufacturers’ value of shipments, the increase in labor prices further places upward pressure on manufacturers to raise prices.

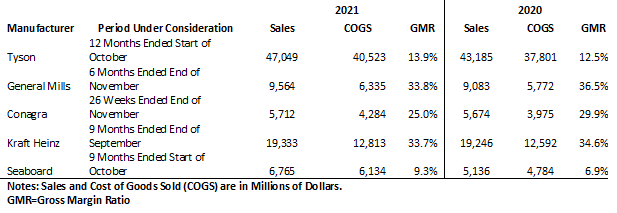

Problem 2: Gross margin ratios for publicly traded food manufacturers in 2021 are not inflated for 2020—they are often lower.

A key metric in both manufacturing and retail is the gross margin ratio, which represents the difference between sales revenue and cost of goods sold then divided by sales revenue. If food manufacturers are price gouging, we would expect to see their gross margin ratios in 2021 exceed their 2020 levels. Unfortunately, some reporting simply looks at gross margin (sales revenue less cost of goods sold) and interprets higher gross margins as evidence of price gouging. That is misguided since the statistics need to be normalized by sales to be meaningful. Therefore, we pulled the latest 10-Q releases from several large food manufacturers. As shown in the table below, General Mills, ConAgra, and Kraft Heinz's 2021 gross margin ratios were below 2020 levels. Moreover, the gross margin ratio increases for Tyson and Seaboard do not seem unreasonably large.