Debate season is upon us for the 2024 presidential election. For the next several months, Vice President Kamala Harris and former President Donald Trump will be trying to rally their bases and appeal to swing voters, and one way they’ll do this is by trying to manage, influence, and harness voters’ emotions. In fact, populist leaders like Trump tend to rely on emotional appeals, especially anger and fear, as they try to connect to their followers.

They are not the first leaders to do so. Both Bush 41 and 43 gained public support after addressing the American people in the lead up to Operation Desert Storm and in the aftermath of 9/11, respectively. This was due to both Bushes’ ability to affect viewers’ emotions.

Leaders can of course consciously try to influence followers’ emotions, but they may still make so-called micro-expressions, which are small facial expressions that happen faster than a full expression and tend to use fewer parts of the face. These are harder for someone to consciously control, so they tend to reflect the authentic, interior feelings of a leader. George H. W. Bush, for example, undermined the potency of his announcement of the Gulf War with micro-expression smiles.

We live in a more politically polarized world and an especially more emotionally polarized America. So, even as broad swaths of American voters agree or only slightly disagree on policy, many Americans affectively dislike people of different political persuasions. In light of this, Walton College’s Jeffrey Mullins and Fulbright College’s Patrick Stewart sought to understand how the United States’ polarized political climate altered the emotional impact of a leader’s speech during a crisis.

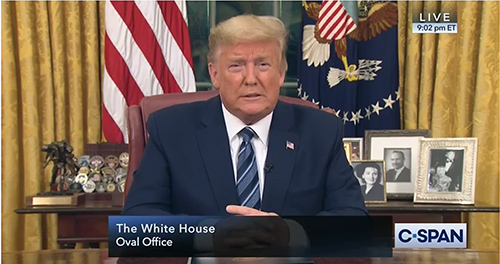

With their colleague Elena Svetieva (University of Colorado – Colorado Springs), they published their findings, “The Influence of President Trump’s Micro-Expressions during his COVID-19 National Address on Viewers’ Emotional Response,” in the journal of Politics and the Life Sciences earlier this year.

The researchers found that their study’s participants’ emotional responses to Donald Trump’s COVID-19 address perpetuated polarization. They also found that Trump’s micro-expression – the lip stretch, an expression of fear – did not undermine his speech. Instead, it acted as a kind of punctuation.

Micro-Expressions are Emotional Leakage

A micro-expression is simply shorter and more covert than our usual facial expressions. They last from half a second to about four seconds, and they are typically registered outside our awareness. Earlier research suggests that even as we try to conceal our feelings, micro-expressions leak our intentions and let viewers read what we wish to keep hidden.

Because they are nigh impossible to consciously control, others tend to interpret micro-expressions as signals of a speaker’s authenticity. For example, when compared against the controlled communication style of Hilary Clinton, who carefully does not use micro-expressions, Donald Trump’s micro-expressions caused viewers in late 2016 to rate him as more trustworthy.

But micro-expressions can also undermine a speaker’s goal when they seem to reveal ulterior emotions. When micro-expressive smiles creep into CEO apologies for wrongdoing, stakeholders notice them and see the apologies for what they are: insincere.

So then, when such a polarizing and ubiquitous political figure like Donald Trump gave a speech intended to rally the country, it gave the researchers an opportunity to test how viewers’ emotional states before viewing a micro-expression changed the way they interpreted it. In his COVID-19 address, President Trump had one micro-expression, the lip stretch, that suggested fear or worry or concern about the ensuing pandemic.

The lip stretch results when someone pulls the corners of their mouths towards their ears. In a sequence of expressions from a slightly open, parted mouth to bared lower teeth, Donald Trump also took a sharp breath, which the researchers say reliably indicates fear with the intent to respond to a threat. It is worth noting that both Stewart and Svetieva are experienced coders in the Facial Action Coding System, which systematizes facial expressions for researchers and animators to better understand what the face reveals about a person’s interior state.

Trump's Speech Drove People Apart

Mullins, Stewart, and Svetieva recruited college students from a class during the spring of 2020, just after Donald Trump’s address and after state governments began locking down. The researchers also had those students recruit more participants to get a more diverse age range. They had a sample size of 252 between the ages of 19 and 82. Their participants had diverse voting intentions as well with 38.2% intending to vote for Trump, 48.2% for Biden, and 13.7% for some other candidate.

Each participant watched Trump’s address. Some viewed the address as it had aired, while others saw an altered version with Trump’s micro-expression edited out. The researchers acknowledge this means the videoclip without the micro-expression has a slight discontinuity of 20 frames, but Stewart’s and Svetieva’s prior research suggests that such short discontinuities are statistically equivalent to their unedited counterparts – something to be mindful of when watching edited footage online.

Mullins, Stewart, and Svetieva found that in general participants experienced a reduction in their positive emotions, especially their feelings of affinity and reassurance, but they did not detect a change in negative emotions. But when broken into pools of supporters, they found that Trump’s supporters felt less angry, distressed, and sad, although there was no change in their positive emotions. On the other hand, Biden’s supporters felt an increased sense of anger and distress with the marked decrease in feelings of affinity and reassurance.

They also found that the followers of other candidates had a much more diverse response to President Trump’s speech. The researchers surmise this is because these participants come from across the political spectrum.

The researchers say that the removal of Trump’s micro-expression only slightly influenced the emotions of their participants. It seems to have reduced feelings of sadness among his supporters, but it had no effect upon Biden’s supporters.

Finally, the team of researchers also had their participants fill out open-ended responses, which they verbally analyzed to get a sense of the participants’ subjective experience of the clip. Their verbal analysis of the responses showed anger correlating as expected but their responses did not reveal their other emotions, even though they had measurably changed. This finding suggests the primacy of anger among emotions.

And similar to their measurement of sadness among participants, they found that Trump’s supporters expressed less anxiety when they saw the version of the videoclip that kept the micro-expression intact. Again, this suggests that at least among his supporters, voters see Trump’s micro-expression as a mark of his authenticity.

Charisma is not Enough

Because Donald Trump’s COVID-19 address was supposed to rally the American populace, his speech appeared to fail: rather than uniting constituents, it affectively drove them apart. There are several reasons this might be: from Trump’s governing style to his insistence on calling COVID-19 the ‘China Flu,’ which many Americans took exception to. Mullins, Stewart, and Svetieva’s work certainly speaks to the difficulty that US leaders face when voting blocs are emotionally primed to respond in differing directions.

They note, however, that this research should not be read as an indictment of Trump’s personal charisma. Participants did in fact respond to his micro-expression. It suggests that followers, would-be followers, and opponents alike attend to the leader and respond to even fleeting expressions. Instead, Mullins, Stewart, and Svetieva say that their findings highlight the importance of studying leaders’ nonverbal communication.

Micro-expressions by their nature do not really lend themselves to actionable advice. But viewers’ sensitivity to them offers a warning to would-be leaders: they should be mindful of their intentions with a speech because their audience will be able to see through their façade as soon as they slip and make the briefest expression outside of their own awareness.